|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 42 |

||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||

|

Source: Spring 2005 Volume 42 Number 2, Pages 35–47 THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD

By December 29, 1940, when President Franklin Roosevelt delivered his “Arsenal of Democracy” speech to the nation, the mighty PRR was recovering nicely from the austerity of the Depression. True, passenger business had continually fallen off since 1929 because of the automobile. But freight business was increasing. Electrification of the northeast corridor between New York and Washington D.C., and between Paoli and Harrisburg was completed by 1938. Maintenance of locomotives, rolling stock, and rights-of-way was excellent so that when the war began they were in an excellent position to do the job they had to do. The World War II years of 1941 to 1945 are considered by many historians to be the high point in the railroads' contribution to this country. The battles in Africa, Europe, and the Pacific would have to be won, but this could not happen unless there was victory on “the Home Front.” This was a war the USA HAD to win!

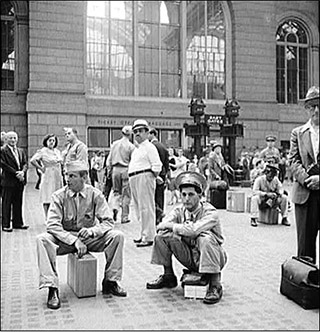

Above: Pearl Harbor changed everything! This 1944 photograph inside Pennsylvania Station in New York City shows the PRR's dilemma: how to manage the timely movement of millions of armed forces personnel AND civilians during WWII. (Internet)* *Image sources are keyed to the box at the end of the article.

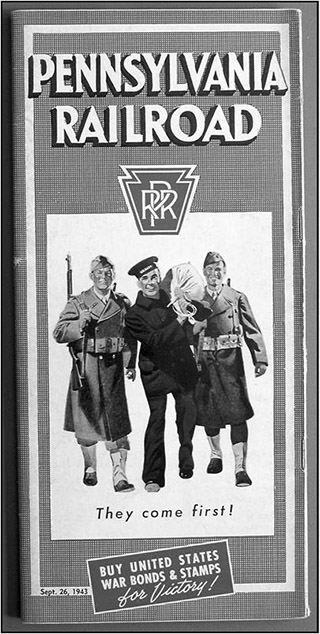

Above: An example of a passenger schedule issued in September 1943 during World War II shows the PRR's priority of moving military traffic. (Cupper)

Left: At the beginning of the war the Pennsylvania Railroad had hundreds of steel P70 “Heavyweight” passenger coaches. shown in this 1944 photograph. This was the standard main carrier for troops and passengers during WWII. The PRR committed a large percentage of its passenger fleet to troop transports because of its strategic geography. A military “consist” could be made up entirely of troop cars, or it might be mixed with civilian passenger cars, or with military or civilian freight cars. Troop movements were always classified, identified only by a Military Authorization Identification Number, or “MAIN,” for secrecy. That secrecy extended to the train crew as well, who were told only their segment of the soldier's final destination. (USASC)

The job of filling a huge troop ship like the Queen Mary with 13,000 soldiers in New York harbor involved as many as 21 trains, comprising over 200 coaches, 40+ baggage cars, and over 30 kitchen cars.

Above: Exterior view of a PRR box car converted into a troop coach and sleeper.” (Hagley).

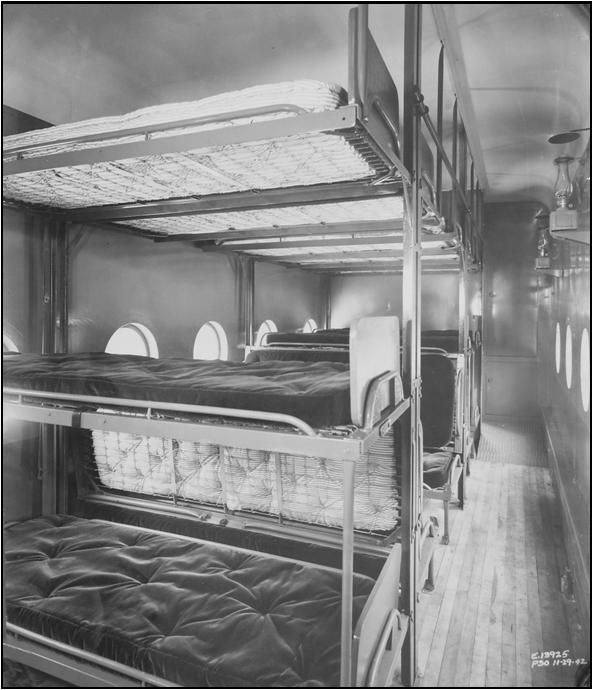

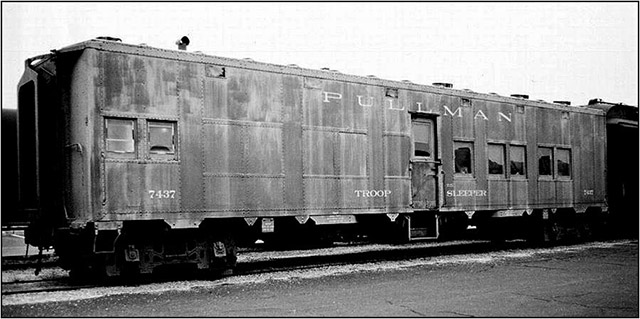

Above: Interior view of a converted box car dated November 29, 1942. (Hagley). When the war began, neither the PRR nor any other U.S. railroad had enough coaches for troop hauling requirements. Beginning in June 1942, the PRR Altoona Car Shop began converting some of its X32 round roof steel box cars into troop coaches and “sleepers.” They cut porthole windows in the sides and added hard riding bunks. The PRR also converted these box cars into dining car configurations with wooden benches. All interior arrangements were very Spartan. Then the government asked the Pullman Company to study the PRR's X32 adaptations, and capture all the PRR features for mass production.

Above: In 1943 the government began accepting delivery on a fleet of troop sleepers and troop kitchens to augment the lack of sufficient alternatives. Pullman built 1,200 sleepers and 440 kitchen cars were built by ACF. Both designs were based upon the common 50' long PS-1 box car. Such cars were generally used in service on a ratio of one kitchen car to three sleeper cars. The Pullman troop sleeper was built with center doors, end doors, and windows cut in the sides. Soldiers squeezed into three tiers of berths. Because the cars continued to use freight car trucks (a frame of wheels under a car), they rode hard, and, lacking air conditioning or ventilation, were dark and stuffy. Each Pullman sleeper car carried 29 servicemen and a Pullman porter. There was little to do aboard except talk, play cards, or sleep. (Internet)

Above: Camp Kilmer, located near Edison NJ, was the largest embarkation post in the United States, and processed more than 2.5 million troops for the European Theatre during World War II. Its rail terminal had a capacity of fifteen 20-car troop trains, with track leading to the rights-of-way of the PRR, the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. (Cupper)

Above: More than any other type of passenger locomotive, steam or electric, the PRR owned 425 of the K4 class (4-6-2 wheel arrangement) locomotives. In this 1946 photograph, a K4 locomotive leads a troop train. A Pullman troop sleeper is shown flanked by baggage cars, with standard heavyweight coaches riding behind. A troop “consist” would vary greatly depending on what equipment was available and how many men had to be moved. The K4s headed the vast majority of the PRR's steam “troop extras” during WWII, with K2, K3, and E6-class locomotives comprising the remainder of passenger steam power. (Heart)

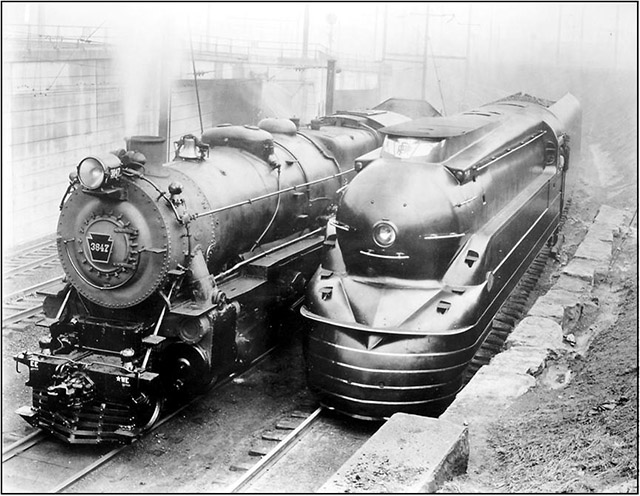

Above: In the late 1930s these two K4 steam locomotives stand side-by-side with and without their streamline shell, the latter an example of the pre-war Fleet of Modernism reflecting the popular Art Deco look of that time. At the time of WWII, the PRR owned 5 of the streamlined K4 steam engines. The streamlined locomotives were designed to haul the PRR's premier passenger trains, like the “Broadway Limited” from New York City to Chicago. The “Broadway” became the ultimate in passenger travel, offering every imaginable luxury and personal service. (Hagley)

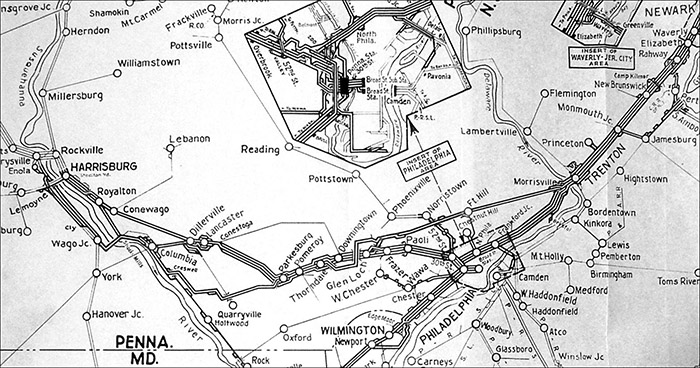

A PRR electrification map, focused from the Harrisburg area east over the Main Line through Thorndale and Paoli into Philadelphia, or over the Trenton Cutoff freight line northeast to the New York City area. (Cupper)

Right: With the electrification from Philadelphia in 1915, Paoli became the western commuter terminus on the Main Line. This rare photo postcard by Skilton shows the covered platform of the eastbound Paoli station just prior to WWII. Most of the PRR's “Blue Ribbon Fleet” stopped in Paoli throughout the war. From 1939 to 1944, the volume of passenger traffic quadrupled on the PRR system. (Postcards)

Above: To provide power on its electrified passenger routes of New York to Washington and Philadelphia to Harrisburg, the PRR had 139 of these sleek and stylish GG1 electric locomotives in its fleet. Shown above, westbound GG1 #4919 stops briefly in Paoli with a passenger “consist” in the immediate post-WWII period. The North Valley Road bridge is in the background, while in the foreground the “spur” track would be used to access the Paoli commuter yard. (Internet)

Right: Framed by a platform canopy and passengers, MP54s occupy both outside tracks at Wayne in this Paoli Local scene common throughout the War. The Pennsy had more than 400 of the owl-faced multiple unit cars, many of them rebuilt from steam-hauled coaches. (Heart)

Above: PRR's Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, built in 1882, was the terminal for the Philadelphia to New York “Clockers” and all Philadelphia to Harrisburg Main Line trains. The large horizontal building seen in the middle housed the PRR general offices. There were 16 tracks. A 1923 fire destroyed the original covered train shed. It was replaced with a series of smaller “umbrella” sheds which can be seen in this 1939 photo. A B1 switcher, seen here, shuttles cars between Broad Street Station and the coach yard in west Philadelphia. Looking east in the far background is City Hall. (Triumph III)

Above: On Sunday morning, September 12, 1943, fire broke out at Broad Street Station. Fanned by a stiff north wind, the blaze leveled all of the canopies and platforms, twisted the tracks, and destroyed the timber shorings. Also badly damaged in the blaze were several passenger cars of the PRR Clocker for New York. Even as the embers begin to cool by the next day, the PRR had rapidly mobilized 1,200 men to rebuild the station. By mid-week several tracks had been returned into operation, and the small army successfully restored the station to full service by week's end. In 1952 Broad Street Station, including the infamous “Chinese Wall,” was demolished to make way for Suburban Station where the tracks were now underground. (Hagley)

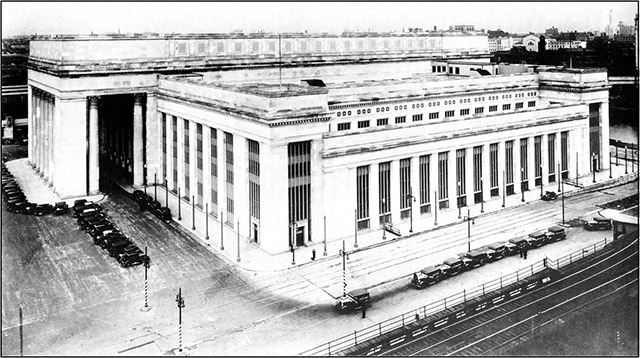

Above: Philadelphia's 30th Street Station—originally called Pennsylvania Station—was completed in 1933. It was the PRR station for its Northeast Corridor trains between New York City and Washington. In this war-era photograph, the trolley tracks for the subway surface cars can be seen along the side of the station and the “el” tracks for the Market-Frankford elevated line can be seen in the lower right corner. Later both of these sets of tracks were relocated underground. (PIM)

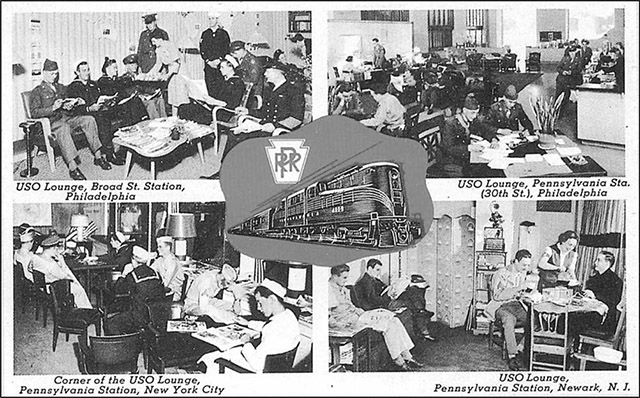

Above: This wartime USO-PRR postcard shows the USO lounges at Broad Street Station and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Station in New York City, and Pennsylvania Station in Newark, N.J. The USO did much to entertain the troops. (Internet)

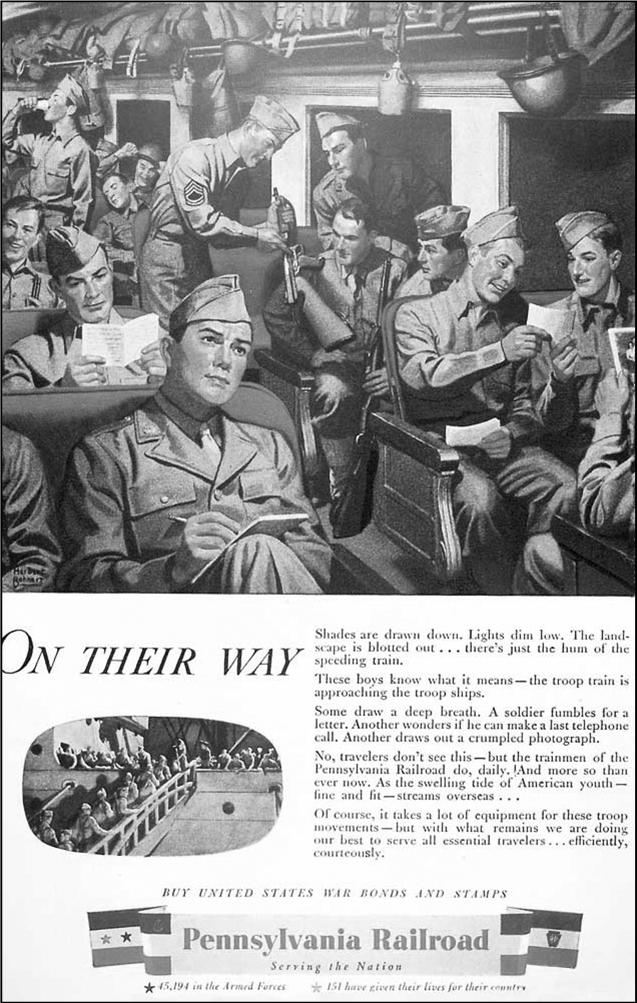

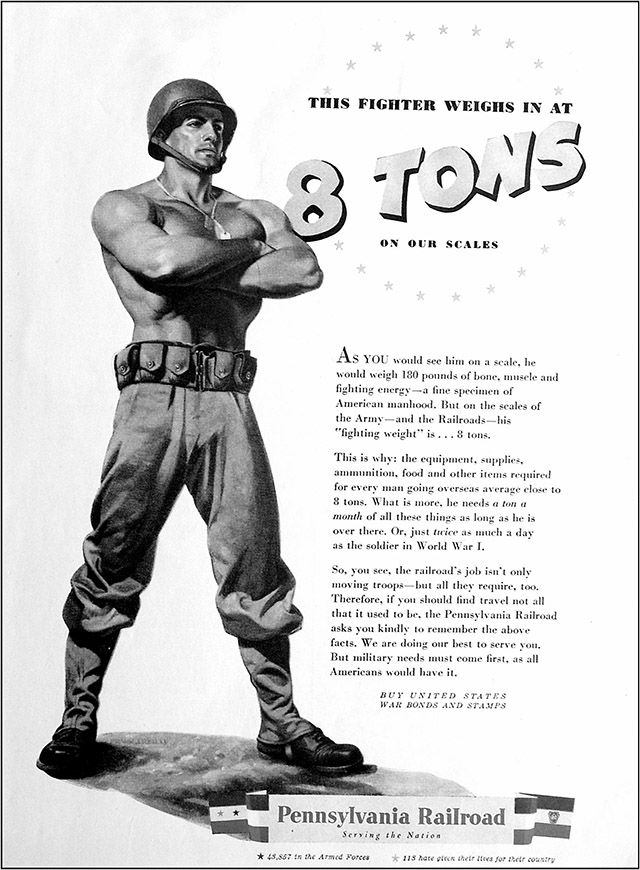

PRR advertisements emphasized patriotism and the need to win the war.

Above: This 1943 PRR magazine advertisement reminds the nation that “the equipment, supplies, ammunition, food and other items required for every man going overseas averages close to 8 tons . . . the railroad's job isn't only moving troops – but all they require, too.” (Cupper). Another advertisement emphasized the enormous task of supporting America's armed forces: “Coordination between the railroads and the ships is essential, and any delay could hold up the sailing of a convoy.”

Above: This PRR advertisement reminds Americans that “first things must come first. And food certainly is a first.” (Cupper). Another advertisement entitled Diary of a Wartime Freight Car–Pennsylvania 59944 shows how this car, and the other 1,800,000 freight cars of the American railroad fleet, serve the war effort by . . . hauling “more tons per trip – over longer distances – at greater speeds – than ever before in the history of railroading.”

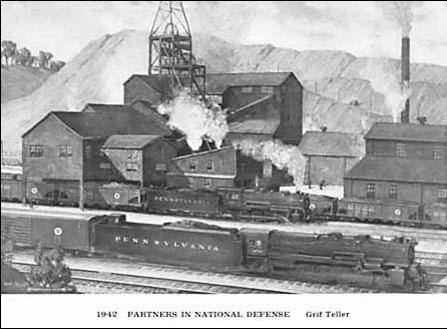

Above: In this Pennsylvania Railroad 1942 calendar cover, PRR artist Grif Teller, depicts the crucial job of hauling coal for the war effort. More than a third of all the hundreds of thousands of PRR freight cars were dedicated to hauling coal. (Hagley).

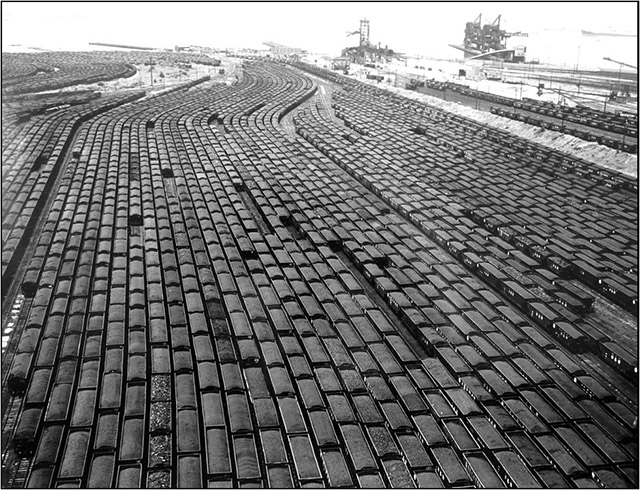

Above: In this extraordinary aerial 1944 photograph, thousands of Norfolk & Western coal hoppers await their turn to unload at the Lamberts Point Transship Dock, Norfolk VA . (Hagley)

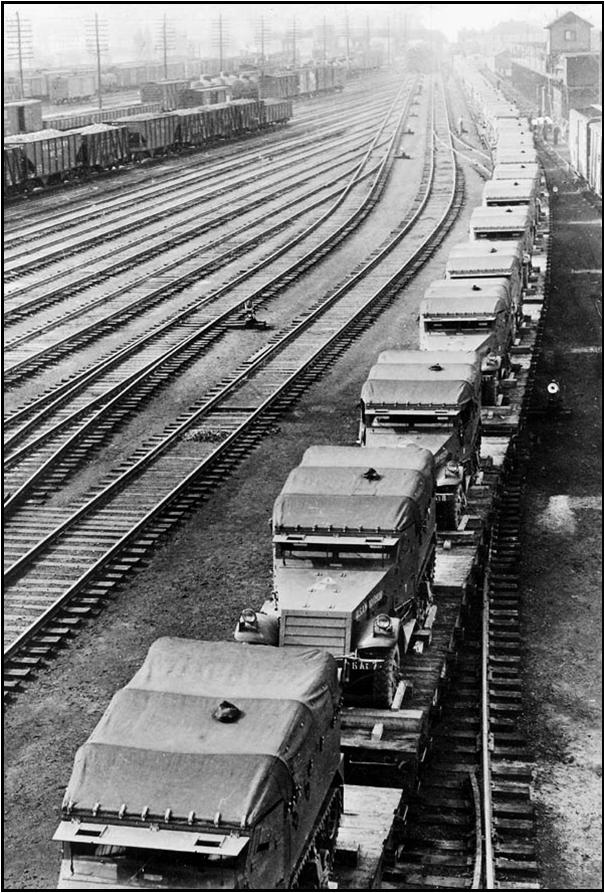

Above: In this 1944 photograph, half-track personnel carriers, here shown as far as the eye can see, are loaded two to a flatcar and secured with wood chocking around their wheels and tracks. Such photographs are scarce because national security forbade civilian photography of military shipments. (USASC)

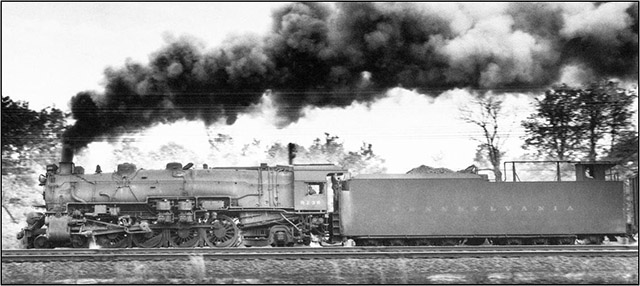

Above: The PRR (2-8-2 wheel arrangement) L1 class Mikado locomotive was, because of their identical boilers, the freight counterpart to the famous K4. The PRR had 574 of the L1 class in its fleet during the war. (Internet)

Above: The PRR (2-10-0 wheel arrangement) I1 class Decapod locomotive 4245 at Columbus, Ohio in 1937. The I1 was a slow freight lugger, called the “mortgage lifter” by enginemen because they were generally not permitted speeds over 50 mph. They often hauled long strings of coal and ore hoppers in hilly and mountainous areas and was mostly seen west of Harrisburg in heavy grades for heavy freight. The PRR had 600 of the I1 class in its fleet during the war. (Internet)

Above: The PRR (4-8-2 wheel arrangement) M1 Mountain class locomotive #6924, photographed in Chicago just before WWII. Called "mountains" because they were big and powerful, they were considered the best steam freight locomotive the railroad ever owned. The M1 became known as "the hallmark of the Pennsy fast freight service." In the 1940s the M1 class locomotive was often seen with a “coast-to-coast” tender, complete with the “dog house” for the head-end brakeman. Because of the significant weight of this locomotive and tender, the M1 class was not allowed to haul freight across the Delaware River bridge at Delair into Camden, NJ. The PRR had 300 of the M1 class in its fleet during the war. (Heart)

Above: GG1 4820 leads an eastbound freight around the curve at Bradford Hills in the 1940s. The GG1, generally used to haul passenger “consists,” nonetheless did its share of freight hauling. The PRR had 139 of the GG1 class in its fleet during the war. (Triumph II)

Above: A pair of P5-A “Modifieds” move oil tankers and mixed freight out of the fog east of the COLA Interlocking (MP 38.4) in the 1940s. These electric units resembled, but lacked the power—or the class—of their GG1 cousins. The PRR had 28 of the P5A Modified class in its fleet during the war. (Triumph II)

Above: P5-A “Boxcab” 34704 hauls a mixed freight under the wires on the New York-Washington Main just before WWII. The PRR had 61 of the P5A class in its fleet during the war. (Triumph III)

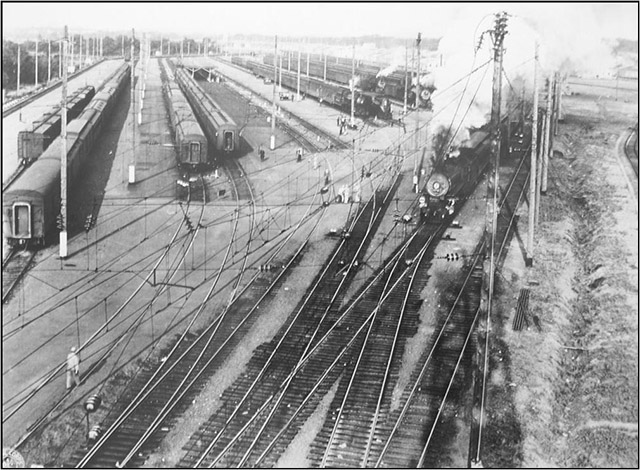

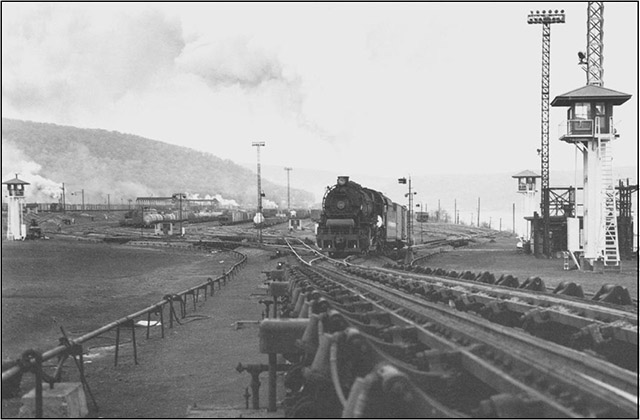

Above: The PRR's Enola Yard held the distinction of being the largest freight classification yard in the United States throughout the second World War. Located on the west side of the Susquehanna River opposite Harrisburg, Enola expanded to 145 miles of track during the war. In 1939 movement through the yard averaged 11,200 cars per day. By 1942 the volume had increased to over 15,750. Enola had its busiest day during 1943 when it processed 20,661 cars within a 24 hour period. Also, as a result of greatly increased freight and a shortage of electric units, the number of steam locomotives serviced at the Enola engine terminal increased from an average of 99 per day in 1939 to 166 by 1942. (Heart)

Above: Heading east out of Enola Yard, PRR freight trains generally followed the A&S Branch (Low-Grade Line) through Columbia and Parkesburg to Thorndale. The Thorndale Yard served not only as a water and coal point, but as a classification yard for local freight service to industries in western Chester County, including Lukens Steel in Coatesville. Shown here is the coal wharf at Thorndale Yard, with strings of coal hoppers and locomotives queued up on March 28, 1937. (Keystone)

Above: An M1 hauling mixed freight on the Trenton Cutoff before the line was electrified. During WWII most freight tonnage was headed eastbound toward the New York City area. Trains heading for this destination had two options to bypass Philadelphia and connect to the freight-only Trenton Branch, also called the Trenton Cutoff. They could either leave the Main Line at Glen Loch—two stops west of Paoli—or traverse what was called the Philadelphia and Thorndale—or the P&T—Line, west of Downingtown. This bypass of Philadelphia ran some 45 miles from Glen Loch northeastward to connect with the Morrisville Yard near Trenton New Jersey and the Main Line from there toward New York City. The Trenton Branch thus freed the PRR Main Line east of Glen Loch from all freight except what was destined for Philadelphia and reserved it for the commuter and fast limited passenger service. (Triumph II)

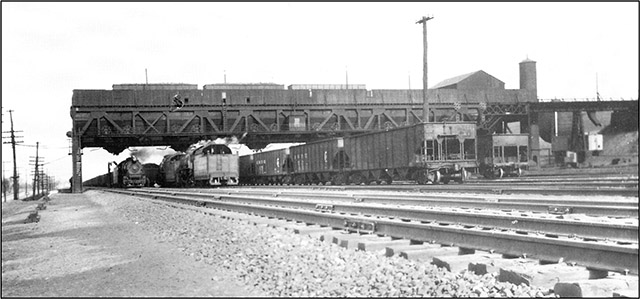

Above: At Whitford, west of the present-day Route 30 bypass in Exton, where the double-track P&T connection to the Trenton Cutoff crossed over the four-track Main Line, hopper cars rumble overhead on the massive truss bridge while below the PRR Chicago-New York Admiral heads east toward Paoli behind a GG1. (Heart)

Above: For freight traffic continuing east on the Main Line, elevation becomes a problem. In the 14 miles from Thorndale to the Greentree—a location between Malvern and Paoli that no longer exists—and Paoli area, the elevation increases 225 feet. Here, L1 #714, added as a “helper” in front of a P5-A at Thorndale, charges east up the grade out of Downingtown toward Paoli. Once a heavy eastbound freight attained Greentree, one mile west of Paoli at mile post 21, (elevation 549 feet), its helper would uncouple and return to Thorndale to repeat the process. (Heart)

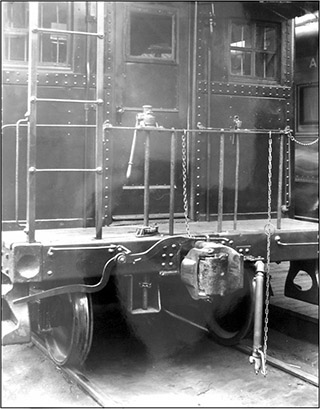

Right: From the highest elevation at Greentree and Paoli it was about a 450 foot descent on the Main Line east to Philadelphia. At this point, the brakemen would engage enough of its freight car retainers to retard the train's speed and the crew would await the dispatcher's signal to proceed. For freight trains climbing west out of Philadelphia toward Paoli, this was one of the toughest grades on the Main Line east of the Alleghenies and “pusher” locomotives were attached to the rear of freight trains at the 46th Street engine house in Philadelphia. Upon reaching Paoli, a brakeman standing on the rear of a caboose—called a cabin car by the PRR—would cut off the compressed air line using a chain, shown above, to detach the pusher “on the fly” and the train could continue west without having to stop. (Hagley)

Above: The Paoli tower was located just east of the division post between the Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Terminal Divisions of the PRR. Constructed in 1896 to operate the interlocking (control the Main Line switches), it also acted as the entrance to the mobile unit yard, seen here with commuter cars. Beyond is the Paoli substation, one of two brick substations built in 1915—the other one is in Bryn Mawr—supplying power to the overhead catenary along the Main Line. (Triumph III) Servicing the Delaware River docks in South Philadelphia, the Greenwich Yard was the primary freight destination for coal, ore, and cargo traffic in Philadelphia. The Yards Were Expanded in 1942, and again in 1944, to accommodate increasing wartime export volume, and route traffic for the nearby Philadelphia Navy Yard. Traffic in the yard increased from a prewar capacity of 2000 cars per day to 4500 cars in 1942, and nearly 5000 cars in 1944. In the 1920s the PRR constructed an extensive South Philadelphia freight terminal and produce yard on Oregon Avenue, along with a 2 million cubic foot cold storage warehouse. This complex helped feed the city during the war.

Above: A Pennsylvania Railroad freight train, with an L1 steam locomotive in charge, charges westbound “under the wires” through Strafford, PA, February 11, 1940. (Keystone)

As more than 43,000 experienced male PRR workers were drafted into the armed forces during World War II, women were employed to help keep the trains rolling. Approximately 22,000 women served the PRR “for the duration” in occupations as diverse as hostlers, ticket agents, trainmen, train passenger representatives, telegraphers, brakemen, and welders. Right [this refers to above image img_v42n2p046c.jpg]: Beginning in 1943, Sada Turnbull served out of Philadelphia's busy Reed Street yard as a freight brakeman. In this PRR publicity photograph, she is shown adjusting the manual brake on a hopper. She received her termination notice in 1946 when servicemen with higher seniority returned from active duty. (Triumph III)

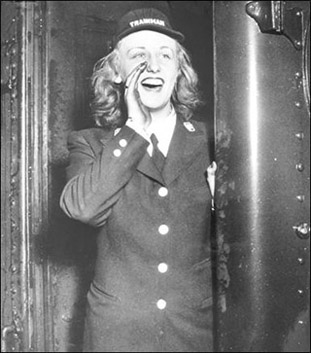

In both these views, new PRR employee, Elizabeth Johns, goes about her duties in 1943 as a “trainman.” On the left she collects tickets on a standard mobile unit commuter car in what could be the Paoli Local. On the right, she calls out “All Aboard.” Notice her sooty hand. Even though this is an electric car, there were many steam locomotives and you could not rub your hand along the side of a coach and expect it to come away clean. (Hagley)

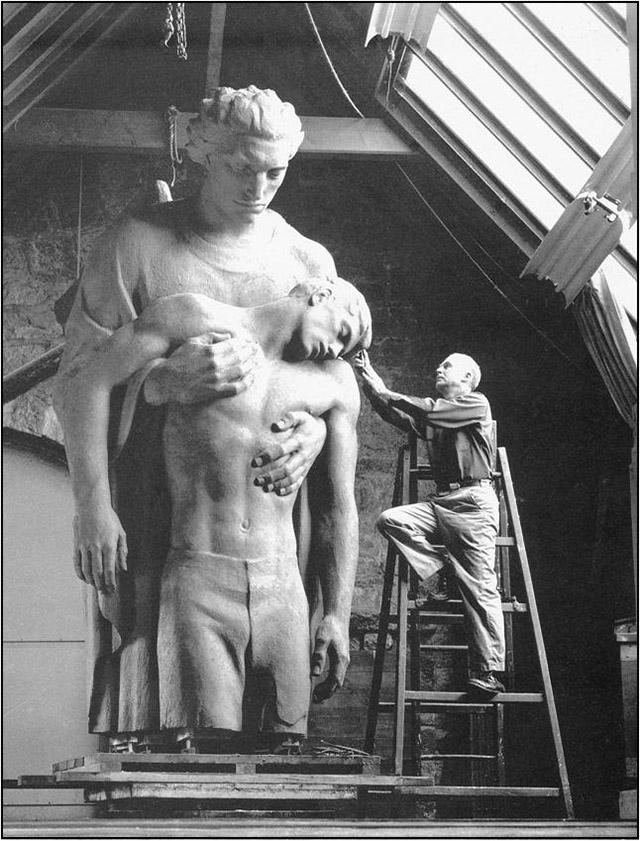

Above: During World War II almost one-third of the PRR's 150,000 employees left to serve in the armed forces. 1,307 gave their lives for their country. Renowned sculptor Walter Hancock is shown with the plastiline model of his statue, The Angel of Resurrection. This large bronze statue now rises on the east side of the waiting area of Philadelphia's 30th Street Station as a memorial to their sacrifice. General of the Army, Omar Bradley, delivered the dedication speech for the Memorial on August 10, 1952. (Keystone)

Cupper – Courtesy of Dan Cupper, nationally recognized railroad historian. Hagley – Courtesy of the Hagley Museum and Library. Wilmington, DE Heart – Robert S. McGonigal. Heart of the Pennsylvania Railroad: The Main Line, Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Books, 1996. Internet – Image provided by author. Keystone – The Keystone, vol. 24, no. 4 (Winter 1991). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society. PIM – J. W. Boorse, Jr. Philadelphia in Motion: A Nostalgic View of How Philadelphians Traveled 1902-1940. Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr Press, 1976. Postcards – Postcards from Paoli album, Paoli Library. Triumph II – David W. Messer. Triumph II: Philadelphia to Harrisburg, 1828 - 1998. Baltimore, MD: Barnard, Roberts and Co., 1999. Triumph III – David W. Messer. Triumph III: Philadelphia Terminal, 1838 - 2000. Baltimore, MD: Barnard, Roberts and Co., 2000. USASC – U.S. Army Signal Corps. This material was presented at the February 20, 2005 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. Carl Landeck grew up in a PRR family, and at the start of WWII obtained employment with the PRR in the Valuation Engineer's Department, the group responsible for the precision of the railroad's maps. He served the PRR “for the duration,” visiting on-site many of the locations covered in this presentation. Although Carl followed a vocation in broadcasting, his love of railroading led to his becoming a charter member and officer of the Philadelphia chapter of the PRR Technical and Historical Society and a PRR historian well respected for his attention to detail. Roger Thorne, who serves as president of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society, remarks that “the opportunity to coordinate a presentation combining the mighty PRR and the “home front” during World War II with a specific focus on the contribution of our local area, was too good to pass up. Many experts and actual participants of that time were there to lend a hand, for which I am sincerely grateful.” He may be contacted at rdthorne@verizon.net. |

||||||||||||||