|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 8 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

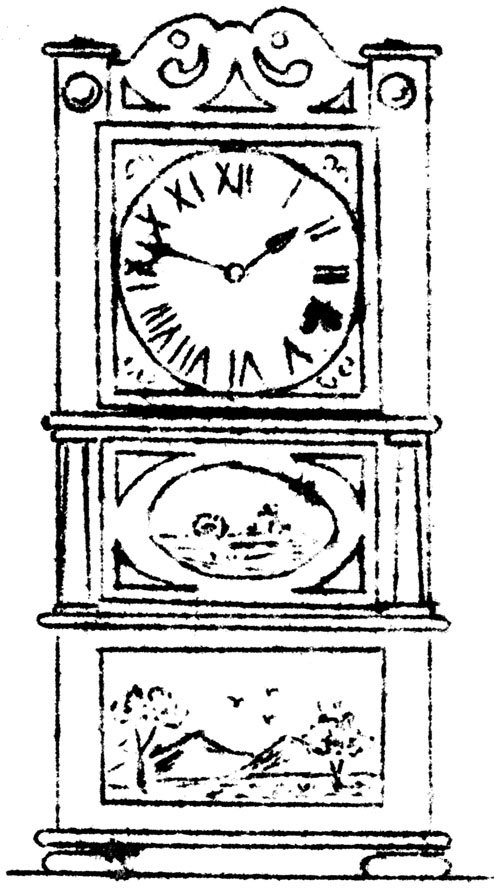

Source: November 1953 Volume 8 Number 1, Pages 15–20 The clocks in my house At the kind request of your fellow-member, Miss Atkinson, I am privileged to address you this evening on the subject "Clocks in My House." I will have to amend that title a little by stating that one of my most cherished clocks occupies a place in my office in Philadelphia and is included for convenience with the others. These clocks are seven in number and are of two groups - those operated with wooden works and those fitted with brass works. All but one were manufactured in towns in Connecticut, and from the uniformity of the parts must have been the product of a very limited number of makers who sold them to various firms who put them in cases and marketed them under their own names. However, this is but a supposition on my part, and I have never encountered any supporting information on this subject. The wooden-works clocks will be considered first, as these were the immediate successors to the "Grandfather" - or better still, to my mind, to call them "Hall" clocks, as they were usually placed in that position in homes so that their striking of the hours could be heard throughout the house. These Hall clocks admirably served their day and generation, which lasted, as nearly as I can make out, from the first importation of their brass works from England about 1760 until desire for cheaper timepieces began to intrude and the inventive skill of the Yankee came into play. About 1813 clocks with wooden works made their appearance, and later under the name "Grandmother" clocks became popular because of their smaller size, daintiness and adaptability for use in various rooms, usually being placed upon a shelf or mantel where they not only performed the duty of telling the time but served also as ornaments. Their day lasted until about 1845-50 when the brass-works timepieces came upon the scene. It is really astonishing that a piece of machinery requiring such accuracy as a clock could successfully and practically be made of wood. The weather has a decided effect upon their workings, and the long uncompensated pendulums have a tendency to extend themselves in hot weather and to contract in cold, yet one of mine to this day can keep time within three minutes per week in any temperature between 40 and 90 degrees, rivaling the performances of brass-works clocks. But my experience has been that a wooden-works clock requires constant attention to enable it to perform properly. It must be oiled at least three times a year, its weight cords regularly examined and replaced at once if showing signs of wear, and minor adjustments, particularly where the power is applied to the pendulum rod, must be carefully made. The wooden clocks ran only for a period of thirty hours, thus requiring daily winding. When the longer running brass rivals came out, reducing the necessity of winding to once in eight days, the wooden-works clocks were outclassed and eventually superseded.

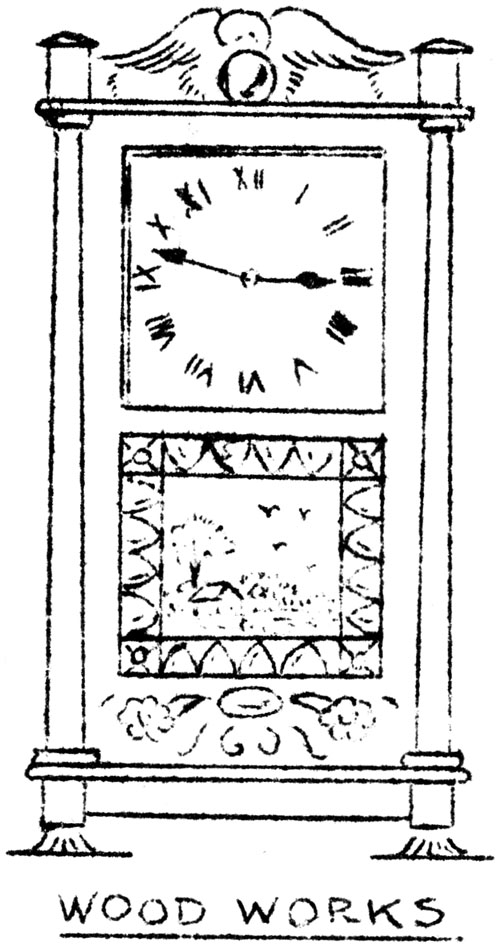

Wood Works Let us now consider this first group - the wooden-works clocks. The works consisted of a wooden frame, usually of oak 8 inches high, 6 1/2 inches wide and 2 3/8 inches deep, containing two trains of wheels - one for the running side and the other for the striking mechanism. Each of these trains consisted of about the same number of wheels; five wheels operate the striking side and eight the running side. These wheels were cut out of what I believe to be selected cherry wood, about 3/16 or 1/4 inch thick, and moved upon steel pins which in turn were fitted into brass bushings in the frame. Every wheel was made of wood except the escapement wheel, which was made of brass, and the escapement itself, made of steel, was a marvelously accurate and reliable piece of machinery, and performed its duty perfectly; it is a lasting monument to its unknown inventor. The wheels were large, averaging about 1 1/2 and 2 inches in size, and each wheel was interchangeable with another of its size and position in the scheme. This is a great advantage, for when a wheel breaks (which many do from age) it can easily be replaced with a similar wheel from another clock. The wooden wheels had one very great disadvantage. The grain of the wood was crossed in their manufacture, thus rendering one part of every wheel more liable to breakage than another. At the present time, I have two clocks with wooden cases, wooden works, and operated, by weights. No. 1 measures 30 inches high, 16 inches wide and 4 1/2 inches deep. This clock was a gift to me from my great-aunt, Mrs. Isaac Pawling, of Paoli, whose husband, my great-uncle, gave me to understand that he purchased it at a sale at Sugartown about 1850. As nearly as I can ascertain, this clock served him all the rest of his life, and after his death in 1902 at the ripe age of 92, my great-aunt presented me with it. It is now running with its second or perhaps its third set of works, although a few of the original wheels are still in use.

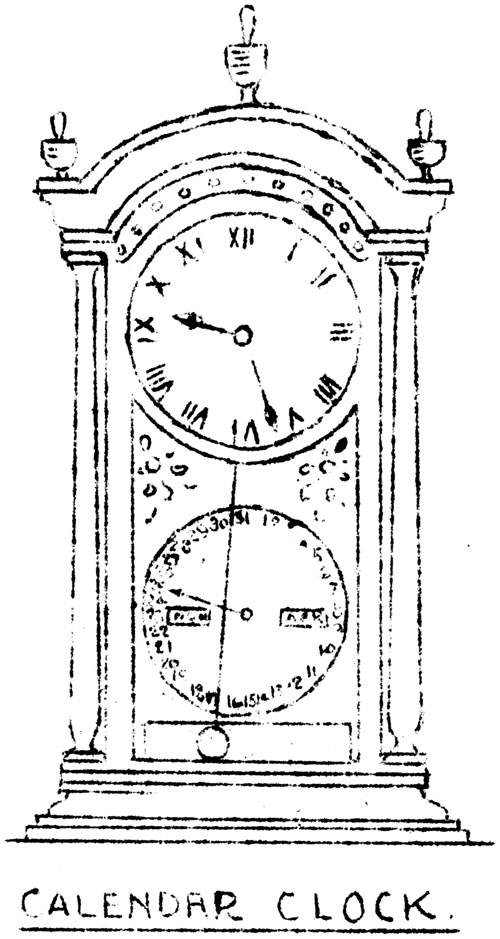

No. 2 clock, with about the same dimensions, is a composite affair, assembled by me. Its wooden case,face and works were all once parts of different timepieces, and as it stands it keeps time almost perfectly and is a reliable guide for catching any train on the Pennsylvania Railroad. It is an interesting piece of machinery. The second group of clocks, comprising those with brass works, number four, they are all of the eight day variety with wooden cases and powered with weights. No. 1 is in my office in Philadelphia and is an excellent timepiece and a fine representative of its period, which began about 1850 and has lasted until the present day. Its measurements are: 36 inches high, 16 1/2 inches wide and 5 inches deep, and the brass frame holding its works in place is riveted together by hand. Its lantern roller bearings must be among the earliest examples of an effort to overcome friction by causing the steel pins to turn in specially prepared bearings as the cog wheels turned upon them, This clock has square-pointed cog wheels - an unusual arrangement which allows them to perform their duty perfectly, and, when you consider the number of tiny holes required to hold the steel pins in place, the labor of fitting them was very great. The trains of wheels (running and striking) are estimated to require over a hundred small holes the diameter of a moderately thick needle to be bored in small brass disks 3/8 of an inch in diameter. This seems to be the earliest attempt at roller-bearings, and it is very evident how effectual they were, for in spite of the wear and tear of nearly a hundred years they still function. No. 2 clock has similar measurements and specifications and the same anti-friction fittings in its lantern pinions. It dates about the same as No. 1. No. 3 clock is older than either of these, and has practically the same specifications, including the anti-friction roller-bearings, but uses the conventional shaped cog teeth instead of the square-pointed ones. This clock is one of the first of this class, and I estimate its age as about 105 years. It keeps very good time. No. 4 clock is of later date; its construction was about 1875, and its brass works were formed in the usual modern way, that is, die-stamped from sheets of brass. This clock, while not in as good condition as the others, performs very nicely, varying not more than 1 1/2 minutes from correct time during a week. No. 5 is a Calendar Clock, that is, a time-piece designed not only to tell the time but also to indicate the month, the day of the month and the day name. This clock stands 37 inches high, 16 1/2 inches in width and 5 inches deep, and its face is 12 inches in diameter. Below this face is a second face of the same diameter, with numbers from 1 to 31 around its edge to which a hand points to indicate the date, while two slots, one on each side of the hand-bearing axle, name the day of the week and the month. The clock was patented by H. B. Horton in 1866 and was made by the Ithaca, Calendar Clock Co., Ithaca New York. It does not strike, and its brass works are comparatively small for the important work it is designed to do, being about 4 x 6 inches in size and 2 1/2 inches deep.

Calendar Clock The mechanism is somewhat difficult to describe clearly, but I will tell you about it as briefly as possible. At the rear of the works is a small cog wheel about an inch in diameter which operates a brass disk of partial elliptical shape which has at one point a direct cutout about an inch deep, toward its center. This cutout allows a projecting rivet from a thin brass bar to fall into the inch-deep cutout. This bar is about 5 inches long, and at midnight descends as far as the cutout will permit, carrying with it two wires attached to the calendar-face mechanism, causing the day and date to change and at the 31st day the month also. This makes some confusion when 30-day months are involved. The day and date then have to be set and the clock then proceeds to register as usual. When I bought this interesting timepiece I had a hard problem on my hands. The small cog wheel was apparently missing and so was the bar to which the wires were attached. I had but once seen such a clock and then had glanced at it but casually, so I was forced to do my own inventing. A super-diligent search of the case revealed the missing cog wheel, and with this essential encouragement I proceeded to gear up the bar to the mechanism operating the calendar portion below. This required the use of either very finely adjusted springs or the application of a gentle but firm force only sufficient to lower the bar at midnight and not to overpower the semi-elliptical hoist at the rear and thus interfere with the time-keeping of the clock. The original maker had apparently exhausted himself with employing springs which did not satisfactorily answer. I worked on the spring idea for over a month, when I became convinced that a small weight would be the real answer to the problem. This was applied with perfect success, and this morning the clock informed me that today was Thursday, July 22nd. This about covers my experience with clocks. I have not worked much upon modern clocks as they just run until worn out and are hardly worth repairing. Electrical clocks do not appeal to me, my interest having been solely in the clocks I have described. Cuckoo clocks do not attract me, although, as a friend recently remarked to me, "You have always been cuckoo about clocks." My one thought in acquiring these clocks was to make them go, as all of them were out of order and could not operate without complete overhauling. The idea that the clocks were antiques and should be restored was not my original thought at all - time-keeping and antiquity were far in the background. |