|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 23 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: October 1985 Volume 23 Number 4, Pages 123–132 Spring Mill

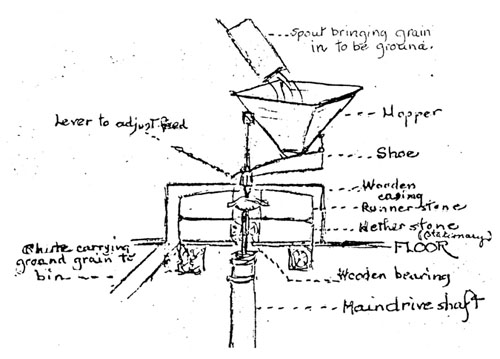

1. Gunkle's Mill : Grace Winthrop Over the door, as you come into the mill, is a date stone: "Spring Mill Michael & Chatharina Gunkle July 20th 1793". (The spelling of "Chatharina' shows that they were Germans; that is the German spelling.) They were my great-great-great-grandparents. Michael Gunkle first came to Philadelphia. He had two brothers who went out to Ohio, but he stayed in Philadelphia and married Chatharina Miller of Millbaugh. Her father owned one of the oldest mills in the state, and was often called "the old miller of Millbaugh". A painting of the interior of his home is on exhibit in the Philadelphia Art Museum. In the 1790 Census, Michael is listed as a buhr maker, living at 8th and Filbert streets with his wife, two sons, and a daughter. (The daughter died in infancy.) In 1792 they came to East Whiteland. He bought almost 1000 acres from an original Penn grant, on which he built a home, a barn, and this mill. (The home originally was not as large as it is shown in later pictures, and was built in two sections.) He was very industrious, and in three years he had three mills operating on this property - this mill, which was a grist mill; a saw mill; and a fulling mill. All three mills were run by water from a lake or pond that he had built with a mill dam across Valley Creek. The mill is pretty much in its original state, especially on the outside. Built of local fieldstone, it has 2-1/2 stories on the front and is banked, the 3-1/2 stories in the rear providing a lower level access for wagons. It did have several particular features, however, that were unique. In the office on the first floor there is a corner fireplace, and the office may even have had wallpaper! There also were no ridge pole and pulley, usually found in mills, to raise supplies to the upper floors. After Michael Gunkle died in 1816, the property was divided among three of his sons, (A fourth son, Michael, his namesake, took 2000 acres of land in Ohio, and moved out west.) The Spring Mill property went to his son John, except for two rooms in the house which, in his will, Michael Gunkle left to his wife. The house originally had one room downstairs and one room upstairs, with a winding staircase, and may have been here even before Michael bought the land. With his growing family, Michael added on the rest. The house is Federal in detail, and obviously dates from the Federal period of 1790 to 1810, In the will it was also specified that John should supply his mother with fire wood for as long as she lived! John Gunkle operated the mill until 1862, In 1863 he sold it to a Jonathan Miller, and he left it to his daughter, Julia, when he died five years later. In 1870 she sold it to Samuel Fetters. In 1897 the property was sold by the sheriff to a Joseph B, Townsend; his estate, in 1913, sold it to a Harry J. Reilly, In that same year Reilly sold it to William W. Atterbury, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, He had a big dairy farm here. When he died in 1937 the property was sold to a man by the name of Wilson Yeager, who continued the dairy farm operation. It was one of the largest dairy farms in East Whiteland Township. Top2. Spring Mill Today : Doris Powell Spring Mill represents post-Revolutionary development in the Great Valley, a period in which trails became wagon roads and then turnpikes, when a greater affluence resulted in the replacement of earlier log structures, once in great numbers, with stone houses and stone barns. It represents the period of a new nation at the time of Washington's presidency. It was our first decade as a nation. Michael Gunkle purchased the original 974 acres, containing choice timber, arable land, and water power, in 1792. By the time of his death, twenty-four years later, he had become one of East Whiteland's most progressive and prosperous citizens, and owned 1343 acres of land here in Chester County as well as 2200 acres in Ohio. In 1810-12 he was one of several local men (another was Colonel Bull, of the Bull Tavern) who financed a section of the Conestoga Turnpike, now Conestoga Road and Route 401, which ran past his mill in a northerly direction. (The venture was not successful!) When the East Whiteland Township Historical Commission was formed several years ago, we became interested in placing Spring Mill on the National Register of Historic Places. We went to the National Liberty Corporation, which had acquired the property in 1968, and they said, "If you want it, you can have it." It was as easy as that! In the summer of 1978 they deeded 1.772 acres of ground to us, including the mill, a carriage house, and a spring house. We received the property in July of 1978, and by December 14th it was on that National Register! Also placed on the Register were a house and smokehouse on the other side of Moore's road. To restore the mill, we asked for and got three HUD grants, totalling $80,000. We used them to put in a new flooring and new steps, things to make the mill safe and usable. With additional monies from the Township, and money we've earned, we have also put in lighting. We still have a lot of things to do - and they all take money. So we are interested in establishing a "Friends of Spring Mill", with a lot of members, to raise additional funds. The restoration work has been supervised by Rudy Fields, a fantastic person from Alabama, full of homespun but down-to-earth advice. He was a millwright, and knows everything about mills. For the main shaft he looked for a large white oak tree (it had to be a white oak shaft), and finally found a huge one in Concordville. From it he crafted the shaft. It is 54" in diameter, and will go all the way across the bay. We have to restore the pier out there to support it, and also clean out the bay. But this is all in the future! If we ever get it running, it will probably be by electricity, though, because the original pond is gone and there's no way to run it today by water power. Top3. Grist Mill Operation : Alice Gilbert Siddal Stray Mills sort of run in my family. For three or four generations there have been millers in the family, or helpers in grist mills. My father was born at a mill over by West Grove which still stands, between West Grove and Chatham - it!s on the National Register as Gilbert's Mill - and I was born there too. So mills have been in my blood from an early age. When I was about two years old, my father, then thirty-two, left home and the West Grove mill and bought Strode's Mill. He ran Strode's Mill for three years, and then sold it and bought the old Taylor's Mill out of West Chester on Route 100 just below the golf course. The only thing I now recognize about that old mill home, where we lived for twenty-five-plus years, is an old scrubby maple tree! The nostalgia of a home at a mill is really great: there's something about a mill - the dampness, the smell, the chaff that keeps falling down. No matter how often you clean a mill, it still keeps falling. Part of the operation of a mill is to clean grain for farmers, for seed and planting. I can remember when I was a young girl, coming down the road from school - we used to walk to West Chester High School, and also to a little one-room school where I went for my first eight years of schooling - I could always tell when Dad was cleaning wheat or oats or something because it looked like it was snowing! The spout that took out the chaff was at the very top of the mill, and the chaff blew all over the countryside - "The chaff which the wind driveth away", from the Scripture, is very apt! So I have a lot of very fascinating remembrances of milling from when I was a young child. I was the oldest in the family, and when you're the oldest in the family (and have good strong muscles!) and your father is a miller and can't find anybody to help in the mill, he expects you to do the work that he wants done. And that's how I learned to run a mill! When the early settlers looked for a place to build their home, the first thing they looked for was a good water supply, and particularly a really good spring. Since they could live in their wagon if necessary, one of the first things they did was to build a spring house, where they could keep their food. (At Strode's Mill there is a marvellous spring, and the spring house had a floor over it; if worse came to worse, one could easily stay there.) Then they would build their house! If they were mechanically inclined, with all the streams running through this area, they would then build a mill to serve the area. The people really needed a place where they could get their grain ground or get feed for their chickens and animals. (They could't just go and get it from a feed store as we can today.) Mills were a real necessity, and there were a lot of mills around. When a farmer had to leave his farm work to go to the mill he didn't want to go too far - and travel by horse and wagon was slow. So mills were in demand, and to have three or four mills along the same stream was quite practical. In addition to grist mills, there were also cider mills, fulling mills, and saw mills. (At the mill where my father was born and worked for his father - and where I was born - there was also a saw mill. It had one of the longest up-and-down saws around. It would saw logs into lumber for the people in the area. Dad made a little model of it that for a time was in Chester County Historical Society, but I don't know where it is now.) Many of the creeks, such as the Valley Creek, a century and more ago were fast-flowing streams. The water supply had not been tapped with so many wells or clogged by pollution, and they were real fast-flowing streams. (If you get up to the falls of the French Creek you can get a feel of the way the streams used to run.) Frequently a mill dam would be built across the stream, forming a mill pond for the water supply. At one time all the area up the road, above this mill, was just a swampy area, the remains of the mill pond, full of mud. The mill dam and mill pond are very important. When you are running a mill for hours and hours and hours, you need to have a large supply of water available. (I remember that once our dam at West Chester filled up so much with mud that we had to have a steam shovel come out and clean out the mill pond and the race. It was getting so full of mud that it couldn't hold enough water to run the mill for more than about eight hours at a time - and Dad would sometimes run the mill day and night, especially during cider season. We had a cider mill, along with a grist mill and flour mill, at West Chester.) The water wheel is the main part of a mill. It supplies all the energy to run the mill. The wheel here at Spring Mill was a big, overshot water wheel, an overshot wheel being one where the water comes in at the top and pushes the wheel down and around. When you start the wheel, you open a little gate on the box that feeds the water from the mill race. The water runs "shussh" into the top bucket, then overflows into the second bucket, then overflows into the third bucket - (we used to watch this happen many times) - and it foams up as it flows from one bucket to another until it gets about one-sixth of the way around. Then, very slowly, the wheel begins to t-u-r-n, and then it goes faster and faster and faster until it is really going, "putt-putt-putt-putt". It's really neat to hear a water wheel start, and then to realize the power that is being generated by it and all the work the water is doing. (When I was in college, my classmates would come out and watch our grist mill run. Most people really have no idea what happens in a mill - and yet mills were a very important part of our country's early life.) The water wheel is fastened onto a strong shaft which runs all the way through the mill. On this shaft there are large gears, which mesh into other gears, and there is a continual working of wheels and pulleys all through the mill. A mill was a place of spinning shafts, crunching gears and slapping belts! (When we were working in the mill, Dad would say, "Always, always wear close fitting clothing. In those days, girls just didn't wear slacks - but we did, because if you wore a skirt you were in a dangerous situation.) Accidents did happen, though, when someone's shirt sleeve or whatever would get caught in the shafts or belts. When a particular belt wasn't being used, it was hung on a peg or tied up with binder twine. And every time some machine was put into use, you had to sling the belt off the peg and put it on a wheel to set the machine in operation. Then when that particular job was finished, you'd take the belt off and put it aside again. You can see the water power that was needed, to run all these belts. Spring Mill was considered to be a very quiet grist mill, because there were only four large gears on the shaft. Even when they were fastened up to run whatever machinery that was needed on that particular gear line the mill still ran very quietly. A mill made as much use of gravity as possible. Grace Winthrop has already commented on the lack of a hoist on the mill here, and I have often wondered about this myself. Whenever you see a mill, except for this one, you'll see a tiny, little out>-jutting gable, and that is where the hoist was. (Our mill had three stories and a basement, and we had to have a hoist. You would pull a rope, and bring the bags of grain up to the top floor.) Since the mill was planned to use gravity as much as possible, you pulled the unground grain up to the top floor, to let gravity take over. Throughout the building there were chutes, from ceiling to floor. The grain would come down these chutes by gravity, into a hopper over the millstones, to start the milling process. Some of the grinding was done on the second floor, and some on the first. On the chute was a handle that you pulled out and pushed in to control the grain coming down the chute. They were pulled out and pushed in so much they had the nicest feel of hand-rubbed wood which was so delightful! Sometimes the chute would get clogged up and nothing would come out, and you'd have to race up the stairs and hammer away on it to get the grain loose. That's why, in the early years, when they were using only the stones to grind flour or corn meal, they had to have a little boy stand by the chute all the time with a stick, and he would hammer, hammer, hammer on the shute and spout that fed the grain into the eye of the runner stone so that they would not get clogged up. Because this wasn't too practical, somebody invented a "hopper boy"; it was a horizontal V-shaped frame which vibrated back and forth and would bang against the spout to keep the grain falling in. So now you didn't need a hopper boy - but the mechanical one was still called the "hopper boy". This mill had two sets of millstones, powered by gears on the main shaft. The runner stone sat on top of, but not touching, the nether stone. In the early years, millstones were used exclusively to grind flour and corn and whatever. Since you wouldn't want the wheat or oats or rye used for flour to run through the same eye or into the same millstone that you would use to grind corn for chicken feed, there were two sets of stones here. One was for grain flour, and one was for cow feed, chicken feed, and so forth. The millstones here were French buhr stones; they are very fine and very, very hard. At intervals of about a month or a month and a half you had to sharpen the stones. A sturdy wooden upright, with a metal arm that looked like a pair of ice tongs, was used in the process. When you had to sharpen the buhrs, you would turn this device to take off the wooden covering around the millstone, and then you would turn it around and use the tongs to lift the runner stone. There were two holes, on either side of the runner stone, and the tongs would fit into these holes to lift up the stone. Then, with a mill pick that was made of steel with sharpened edges, you would pick, pick, pick. (Dad would take a stick or board that had red chalk on it and run it over the stone, and wherever you saw the red on the stone you had to pick, pick, pick.) Around and around and around you'd go, and the sparks would really fly! But it was really necessary, because if you didn't have sharp buhrs, the grain didn't "get ground finely enough, and you just get a mush or paste.

By Alice Gilbert Siddal The buhrs were raised or lowered to make either fine ground or coarse ground corn. Corn meal was ground very fine, and many farmers' wives made large kettles of mush, to be used as a hot cereal, or sliced when cold and fried. Dried beef and gravy over fried mush was a real "stick-to-the-ribs" family supper. One of the joys of milling was making corn meal for mush. The very finest corn meal is made of parched corn. Some farmers' wives would take the lovely yellow corn and shell it, and then very lovingly set it in the oven and stir it until it got a golden yellow - not burned, nor even really dried out, just parched. And then they would bring it to the mill and Dad would make it into corn meal. Sometimes he would bring in a scoopful of this corn meal that was made from the parched corn, and Mother would make a pot of corn meal mush. There is nothing more delicious to eat than corn meal mush that has been made from parched corn! It was nutty. It was tasty. It was delicious. Words can!t describe it! Sometimes the wheat brought to the mill was really bright and crisp looking and shiny. When you take some of this beautiful wheat, the grain, and put it in water, let it soak, and then boil it up, it will "burst-its-buttons" and make a chewy, gum-like type of cereal. And when you put sugar and real cream on top of it, it was the most delicious breakfast food you would ever want to eat! With the growing demand for flour, many mills later became roller mills, and began to use very fine steel rollers or grinders instead of millstones. (Dad had one in our mill over at West Chester.) They cut into the wheat must faster than the millstones we have here at Spring Mill. But a lot was also lost, because the steel rollers heated up much more than the stones did. Home bakers also complained that their bread lost its "keeping" quality, and that the flour was deprived of many of its nutrients by this new method of grinding - but the miller's profit from more flour for less time won out over the bakers' complaints! After being ground, you have to seive, or "bolt", the meal. The bolting cloth was a strong, sheer silk of the best quality, imported from France, stretched over a rectangular frame. As the meal is sifted, the fine white flour is separated from the brown husks, or "middlings", and from the bran. The middlings were used in scrapple and things of that sort. (In our mill at home, at one time Dad was making middlings and corn meal for three different butcher shops - Habersett's, Titter's, and Strode's.) In those days they didn't pay much attention to the bran, though they sure do now and for your health you eat a lot of bran. But in those days, the bran was mixed with the slop for the pigs! Every night it was swept up, and that's how we got a lot of chicken feed too, as the bran was mixed with flour from bags that the mice had chewed holes into. Mice were always living in the mill. One reason was the corn cob bin. You always had some customers who did not want the corn cobs ground in with the corn for their cattle feed or chicken feed. And so you'd shell the corn first, and the corn sheller would spill out the corn cobs into a corner of the mill that was closed in with wire. That was the cob bin. If you wanted a mouse for a scavenger hunt or treasure hunt, you could always get one by going to the cob bin. You'd see something moving, and then you'd grab its tail and keep pulling and pulling and pulling until you could grab the mouse behind the neck. I did it many times. Once I pulled the tail right out of a mouse! (I don't know whether it ever grew another tail or not, but I pulled it out!) You also always had about four or five cats around. They were the mill cats, and they were important too. There were also always a lot of birds around the mill. We had flocks of English sparrows, which would frequent the mill, and outside it where the grain came down the chute into the wagons, and flocks of grackles and starlings. You can see that the bird population throughout the years also changes. Every once in a while you might see a sparrow hawk which had come in an open window or through an open door, and was after the English sparrows. It was important to keep the mice population down to a degree, but it was a must to keep the muskrats out of the mill race since they bore holes in the banks and let the water run out. The first thing you knew, you'd have a big opening in the bank and your water supply was diminishing - all because the muskrats were doing things they shouldn't do to the mill race! There's plenty of room for muskrats out in the swamp! These are some of the things you always had to be watching for. In a rainstorm, while it was still raining, Dad was always out in his old raincoat with a rake. He would go up to the mill race and open up all the little gates to let the water out, so that the water wouldn't overflow and wash away some of the mill race banks. (When you had a real. long mill race, that was quite a job; sometimes I'd help too.) Then, after the rain stopped, you'd go out and shut them down again, so that you could save the water. You always had dust in a mill. If you didn't have on white clothes, you looked white anyway. (For me, a mill always smelled of the tar used to lubricate the belts, mingled with the smell of corn cobs and ground, wheat - and dust. It was a neat smell! When Dad used to run in for dinner he didn't even take off his white cap, because if he did the dust would be all over the house.) But you always had to keep the mill as clean as possible, to reduce the possibility of fire. There never was any spontaneous combustion in our mill - never. It has happened, though, and so you had to keep the dust down. You went around with a broom to sweep down the cobwebs, which were always there, covered with dust. After the grinding was done and all the grist bagged, the farmers came to get their grist. It was always quite a job to get their wagons loaded properly. (I can remember at times we had grist piled up in bags all the way to the ceiling, waiting for the farmers to come and get it.) You really needed a lot of space just to hold the ground flour, and the floor of a mill was like a maze. We tied the bags with binder twine. You had to pull the twine tight, because if the bag wasn't tied up tight, when you put it in the wagon the top would become untied and the farmer would lose all his grist. More than once (but not too often!) I was scolded because I didn't tie the bag tight. When you pull the binder twine tight, it kind of screeches, and when it screeches, you know you have a good, tight pull. A mill used an awful lot of binder twine. The flour was also put in barrels. (I can still see Dad putting the lid on a barrel of flour or on a barrel of corn meal.) In the early days of selling flour, the barrels had to be carefully inspected, because some of the millers in those early years would try to get away with something. The inspector would bore a little hole in the bottom of the barrel, because some millers were putting in a false bottom. Instead of getting a whole barrel of flour, you'd have a space where there was nothing! Spring Mill sold many barrels of flour, all of which were stencilled, with the mill's logo. Some of the stencils used here on bags and on barrels of flour had "CCC" or "XXXX" on them. These showed that it was an unusually fine brand of flour. (Fine flour wasn't always an advantage, however. When we had Strode's Mill during the First World War, there were inspectors who went around to make sure that you weren't taking too much out of the flour. As a wartime measure you were expected to leave some of the middlings in the flour. So this inspector came around, and asked, "Gilbert, have you changed over for wartime flour?" And Dad said, "What do you mean, 'changed over'?" "Well, are you making flour to the standards of the government?" And Dad said, "Well, I'm making flour, and if you want to see how the flour is made, fine. Do you know how to make flour?" "I have no idea," he said, and Dad said, "I thought so!") Spring Mill was a grist mill for about 80 years, but after Mr. Fetters bought the mill it became a merchant mill. When a mill just does custom grinding for farmers, it is called a "grist" mill, but when the miller buys quantities of wheat and sells many barrels of flour, the name "merchant" mill is used. Mr. Fetters saw a need for supplying flour to the growing populations of Philadelphia and Lancaster and Wilmington, and realized that the railway, then the Chester Valley Railroad, running near his mill could provide the necessary transportation. Being a business man, like Mr. Gunkle before him, he decided that here was a chance to make some money. The farmers in those days had trouble, and didn't make any money, and so they couldn't pay their bills for flour. (I can remember that even in the '30's they still didn't have much money.) So the miller would simply keep some of the grain for payment, instead of having the farmer pay any money. The records were kept on a toll board that showed the number of pounds of grain ground for each farmer. In the Jeffersonian for September 21, 1872 Fetters' Mill was described as "a large business". "Of the county grist mills", it was reported," throughout Chester County, there is probably no one that surpasses in business the one owned and worked by Samuel Fetters, known as 'Spring Mill' in East Whiteland Township. The monthly quantities of grain, flour, etc. supplied to customers from this mill are as follows: Corn, 50 tons; Flour, 200 barrels; Oats, 1000 barrels; mill feed, from 50 to 60 tons. The mill is required to run 18 hours out of every 24, Sundays excepted, in order to meet the demands of the patrons, and even with this effort on the part of its go-ahead proprietor, he sometimes falls short. During the last year he has hauled from his mill with one pair of little mules, over 18000 tons of flour, feed, etc., and his business has now so increased that he has found it necessary to double his means of transportation, and to this end he one day last week purchased another pair of mules." In November 1894, it was reported in the Chester County Democrat "Carpenters are building an air tight and frost proof house over the twenty foot water wheel at Spring Mill. The mill has a capacity of about fifty barrels of flour in eighteen hours at present, which can be further increased at short notice to one half more. Some new improved flour dressing machinery will be added, also more smooth rolls and another purifier, all in the near future as the rapidly increasing flour trade demands additional machinery to keep abreast of the times." So these are some of the nostalgic memories that come to me when I am in a mill - and that's why I like to talk about a mill. I hope this will give you a feeling of all the belts and machinery, and the sacks of flour and grist, and all the activity and work that was going on in a grist mill like Spring Mill. |