|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 39 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: January 2001 Volume 39 Number 1, Pages 13–26 Club Members Remember: Traveling by Train Herb Fry It is over forty years since the technology breakthroughs created in the aftermath of World War II relegated the passenger train to the sidetrack of choice by the traveling public. The number of automobiles produced rose exponentially, and the Boeing 707 jet-liner seating 200 passengers made its debut in 1958. Flying was soon to become the accepted norm when embarking on long-distance travel. By the 1960s the railroads were abandoning most passenger service, and in 1970 the Pennsylvania Railroad, after its fateful merger with the New York Central, declared bankruptcy. Since few of the "baby-boomer" and later generations have ever traveled by rail, it might be useful to reflect upon and record our experiences "traveling by train." My first experience with long-distance train travel came courtesy of the U. S. Army. In early September of 1944, after processing with a batch of raw recruits at New Cumberland outside Harrisburg, we boarded a troop train in the early evening under strict blackout regulations for our basic training - destination then unknown. Accommodations were standard Pullman sleeper with lower and upper berth. My lot was the upper berth. Awakening the next morning, it was soon apparent that we were in the Carolinas -and without air conditioning, it was noticeably warmer. A long day's journey lay ahead, unfamiliar army chow served by army cooks in the kitchen car and, finally, at dusk, our destination deep in the oak-pine woods and swamps of northern Florida. Camp Blanding would be "home" during our weeks of basic training. In the future lay some not-socomfortable travel on the bombed and strafed railroads of Europe in their 40 & 8 (40 hommes & 8 chevaux) box cars. Ten years or so later, around Easter of 1956, my work as a CPA took me to central New York state where a client company had bought a chain of grocery stores. They were called Market Basket, and their headquarters was in Geneva, New York, at the upper end of Seneca Lake. I was to oversee the transfer of accounting records to Philadelphia. It was very convenient to book space on the sleeper which left Reading Terminal at 10:30 p.m. bound for Buffalo. The Philadelphia car was hooked up in the Bethlehem yard with a train on the Lehigh Valley line from New York City (the "Black Diamond," I believe), and you woke up the next morning around Sayre, Pennsylvania or Elmira, New York. There was time for breakfast in the diner because it's a long trip along the lake to Geneva. When the next big chain store acquisition took place in 1961 it was in California, and the decline of long-distance train travel had taken its toll. On this trip to meet the West Coast accountants, I traveled by air -- TWA! Steve Dittmann The Republican National Convention to nominate a candidate for president in the next election took place at the First Union Center in Philadelphia on Friday night, and I was there to see some of the events. One thing I saw was 12 bright yellow railroad cars of the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska. Although I did not make a trip Friday night, I had an opportunity to go through each one of the 12 cars. They were built in the 1940s or 50s; three were observation cars, two were locomotives and the rest were things like dining cars and executive cars. It was quite an experience to see how the Union Pacific today still maintains this equipment for special events, including this week end's R.N.C. As I was leaving I had an opportunity to get a complimentary picture. You also hear (this is only scuttlebutt) that after George Bush is nominated president, on his way back to the West, he will ride in this Union Pacific train, picking it up in Pittsburgh and going out to Chicago. So that's just what I heard. My trip Friday night didn't go anywhere, but I had a great opportunity to see the Union Pacific trains, and it did remind me of a trip I took in 1954 with my mother overnight in a sleeping car from Philadelphia to Niagara Falls. Mary Lamborn This is going to be short. In the fourth grade, the early 1920s, I made the shortest trip. It was from Berwyn to Strafford on the train, and then by trolley from there to Upper Darby and the elevated train into the city. It wasn't far, but for a young girl from the country it was a big event. Mary Ives Back in the days when all the Pennsylvania Railroad trains going from New York to the West stopped in Paoli, I took two wonderful trips across our country. In 1955, I took a northern route, boarding the train in Paoli and sitting up during the overnight trip to Chicago. After a lay-over of several hours, I climbed aboard a train on the Milwaukee Road, which is no longer in existence, and having treated myself to a bedroom, made myself comfortable for the next three nights and two days. The train was beautiful, the food was delicious, and the train had dome cars on it where passengers could go to an upper level to watch the scenery. In addition, we were given a pamphlet describing all the places we would see and giving some history about them. We went north through Wisconsin to St. Paul and Minneapolis, and then turned west crossing Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Washington. It took 17 hours just to get across Montana. At one point along the way the train stopped, all the passengers got off, and we watched while some sort of mechanism washed the outside of the passenger cars. The railroad did not go through tunnels to get through the Rocky Mountains in Western Montana and Idaho. Four diesel engines pulled the train over the mountains, sometimes going so slowly we were barely moving. Of course, the scenery was beautiful. Eastern Washington was very flat, but we then came upon the Cascade Range which to me was even more beautiful than the Rockies. We saw many evergreen trees, and in some places sheds were built over the tracks to keep snow off them in winter.

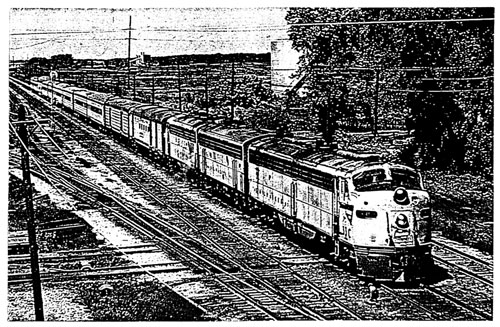

Milwaukee's "Hiawatha" southbound from the Twin Cities to Chicago about 1960. Note the full length dome car and the unique sky-top parlor observation car.

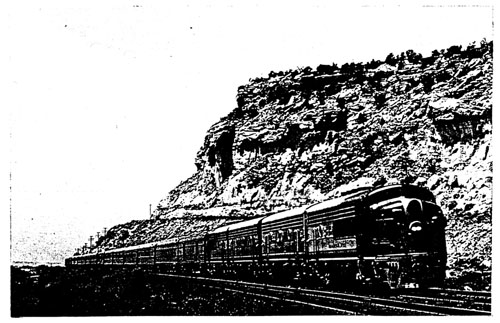

The Santa Fe "Chief" with its War Bonnet design near Valentine, Arizona, westbound for the Pacific Coast about 1960. The end of my journey was Seattle, where I visited the girl who had been my roommate when we were stationed in Iceland in 1943-44 during the war. We had a good time together seeing her part of the world. I returned by train from Seattle. After we left Chicago I made sure the Pennsy conductor would stop in Paoli to let me off. The eastbound trains did not stop to take on passengers in Paoli. Several years later I again boarded a train in Paoli bound for Los Angeles and San Diego. I had a bedroom all the way because my railroad car made the entire journey, this time on the Santa Fe line west of the Pennsy terminal in St. Louis. Again we were told about the sights along the way. Of course this was a more southerly route, and the land was flatter and browner - lots of desert. In Kansas City our car was detached from the train and left there for about 12 hours. Not too far from the station was the Crown Center, owned by Hallmark Cards, and several of us went there to see the hotel and the lovely shops and to have dinner. Back on our railroad car, we went to bed and sometime during the night a train from Chicago picked up our car and off we went across Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and into California. One stop, I remember, was at the little town of Gallup, New Mexico. My sister and her husband worked among the Navajo Indians at one time, and their oldest daughter was born in a hospital in Gallup. When I arrived in Los Angeles, I changed trains for San Diego where I visited another friend I had known in Iceland. Airline accommodations were becoming more usual by this time, so I flew home from San Diego. Bill Andrews Today when you travel by air, you go through a whole rigmarole, finally get a ticket, go to the airport an hour and a half ahead of time and then stand around. You turn in your ticket (maybe six pages, or more) and get herded aboard like sheep. Now, I remember a trip to Boston that was so simple. I bought a ticket, about this big (inch and one-eighth by two and a quarter inches), Philadelphia to Boston. You carried your bag with you or else checked it through on the train. You got on the train, changed at 30th Street. That was the whole deal. Jim Houston I was born and raised in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and I decided to go on the railroad right before the Second World War started. So I took an application in to the Pennsy employment office and, to my dismay at the time, they said, "You're going to be on the Paoli Local." Well, I didn't know much about anything along the Paoli Local, but I found out that all of the stations were approximately one mile apart. I don't know exactly when they decided on them. The stations were built before the towns became towns, because it was almost all graze land or whatever it was. When I came on it was 1941. I was only on the railroad one year as a passenger brakeman, and then I went into the war for four years. After the service I came out and continued on with the railroad. I was there 42 years, and of the 42 years approximately 30 years were on the Paoli Local. I had a regular run because I became a conductor, so I had a train that I had almost all the time with my regular people. I started out with the old red cars, no air conditioning, and eventually they were improved to where they are today. But I enjoyed it, and I ended up with Amtrak going between Philadelphia and Harrisburg. That was my experience with the railroad. Sometimes even now people say, "Don't I know you from someplace?" I say, "Well, I don't have my hat on!" Barbara Fry From 1946 until 1950 I worked at a department store in my hometown, Binghamton, New York, and commuted by bus to college in nearby Endicott. I did not plan a career in retailing, but after a time I was moved from my floater position at the store to a regular place in the hosiery department. In those first years after World War II, with nylon again available, hosiery was a hot item and the department was carefully monitored by the store's president, Benjamin F. Sisson. The hosiery department was plagued by inventory problems, and finally the buyer left. When fill-in stock was needed, Mr. Sisson would call me to his office and we would make purchasing decisions. When the time came for a buying trip to New York City to view the next season's styles, I was invited to go along with the "real" buyers. The train that carried passengers from Binghamton to Hoboken was the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western. From Hoboken, travelers went either by ferry, or into "the tubes" under the Hudson River to reach Manhattan. I had never traveled this line, but from childhood on I was taken to the great Binghamton station to meet relatives arriving from the West and to send them off again when they returned home. The noise and the energy of the engines roaring and clanging into the station through the dense white steam was always a powerfully exciting moment. The store allowed each buyer a fixed sum for transportation, food and hotel accommodations. Rates on the Lackawanna ranged from sleeper down to a night trip on coach that made every stop. I chose the latter, seeing no problem with sitting up all night in coach. I left Saturday night after a long work day. This gave me a Sunday free in New York. Arriving in Hoboken after a long, long night, and armed with carefully detailed directions from the experienced travelers from the store, I quickly found "the tubes" and in no time I was in Manhattan. I checked into the Astor Hotel at 42nd Street and Broadway. After an ambitious day in New York, I went to bed early. I was awakened the next morning by the telephone. It was not my 7:00 a.m. wake up call. I never knew what happened to that. It was 9:00 a.m. and the linens buyer wanted to know why I was not at McGreevey, Warring and Howell, our buying office. I was ready in record time, and arrived at the buying office to amusement rather than anger. Mr. Sisson was soon ready to set off for the hosiery houses. He made a fine impression in New York with his tall, regal bearing, closely clipped waves of white hair and well tailored suit. I think his peculiarities were really games he played for fun. I was warned he would "hum" in halls and on elevators. We spent much of the first day at the Empire State Building where most of the big hosiery houses kept beautiful offices. We rode the elevator from one to another, and "hum" he did. We had lunch at a French restaurant. My sandwich came open faced, and I had to take a cue from other diners on how to eat it. All the food in New York was superb. That night I went to dinner with the other buyers, and then we all went to see a stage show, "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," starring Carol Channing. On Tuesday my schedule kept me in New York past the time the other buyers left. I reached Hoboken with just enough time for dinner before the train. I was alone at the counter. My meal was perhaps the best I have ever eaten, just ham and pancakes, served elegantly as train meals always were, by the gentleman behind the grill. The train home made fewer stops. I soon was given the title of hosiery buyer, but I would make only a few more trips before I married and moved to Philadelphia. In 1949, the president of the Lackawanna, William White, named his crack new luxury train the "Phoebe Snow" and revived the legend that had first appeared in 1903. The railroad at that time owned an anthracite mine in Pennsylvania. They produced and burned hard coal as opposed to bituminous coal used on the other railroads. Anthracite burned with less dust and soot than soft coal, so the ads showed that Phoebe, dressed all in white, arrived at her destination still the color of pristine snow. This campaign by the Lackawanna produced a number of jingles on advertising cards. The first of many was:

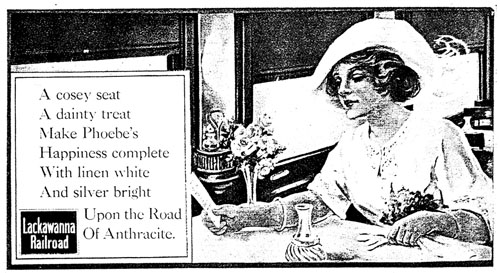

Says Phoebe Snow The legend persisted for a generation until World War I when coal shortages forced the Lackawanna to burn bituminous coal. Another Phoebe Snow operated briefly in 1930, and yet another during World War II with this advertising jingle:

"Our first job now," The schedule for the Phoebe Snow in 1949 cut the time from Hoboken to Buffalo to eight hours. This was during my railroad traveling days. Even if the Phoebe was not on my schedule, the Lackawanna at this time was making efforts to upgrade all of its trains, and the service was good.

In 1960 the Lackawanna merged with the Erie, a freight line. Passenger service was chipped away, and the Phoebe Snow was discontinued in 1962. A brief restart in 1966 scheduled Phoebe to Chicago over other lines, but in November of 1968 it was shut down forever. The Interstate Commerce Commission would not give permission to abandon passenger travel, so for a time it was still operating in a manner to discourage even the hardiest passenger. The one train daily left at 12:15 a.m., with only one car and taking eleven hours to complete the run to Buffalo. Finally, the old Buffalo Station was sold, and passengers were put off a few miles short of the city in an industrial wasteland. [N.B. The Phoebe Snow lore is taken from an Oliver Jensen story in the December 1968 issue of American Heritage Magazine, "'Bye Phoebe Snow, 'Bye Buffalo," pp. 10-15.] Howard Housworth I once followed the same route that Mary Ives followed. It was during World War II. I left Fort Meade, Maryland, with a troop train and we went west. I guess it was the Pennsy then, a steam train. I remember we crossed the Mississippi river at Davenport, Iowa, and then we ambled on north and zig-zagged over the line of North and South Dakota. We went into Montana on flat tableland for miles. No wonder they call it "Big Sky" country, it was a beautiful trip. I'm not sure where we were, but I remember one morning looking out the window and seeing mountains off in the distance. I said to myself, "Oh boy, tonight when I go to sleep we'll go right through the mountains and I'll never see them." The next morning I woke up and we were just about getting there. It took forever to get to the mountains. We were on the Milwaukee Road, and the part we were on was pulled by electric. The train zig-zagged through the mountains. I remember a couple of times the train went through two tunnels with a bridge connecting the tunnels! You could see both ends of the train at the same time because of the curved track. You couldn't go fast. I looked down and there was a little road paralleling the track, with a mountain stream alongside. It was absolutely beautiful. I think it was June of 1945 approximately. The weather was perfect. There was no air conditioning on those Pullman cars, every window was open, men were sticking heads out admiring the view. Once I looked back inside and there were two guys reading comic books. "Hey, you guys," I said, "you'll never see the country again. Here you are reading comic books." The plea fell on deaf ears. Finally through Montana, we stopped in Idaho in a gorge. I remember it was just a little village in a gorge. We were trying to get into a store that sold fruit. I had my eye on on some strawberries, but they turned out to be not worth buying. They had been sitting there a long time. I guess we were only there a half hour or so. We proceeded on our way. We went through Washington, and we ended up in Oregon where we waited for a week or so before we went overseas. Going through Washington, I remember seeing these railroad cars that were just loaded down with logs. They only got two or three logs on each car they were so enormous. It was just fascinating to an Easterner who never saw a tree that big before. We got to Oregon and eventually overseas. It was a very memorable trip. That was worth seeing. I was on other troop trains. Later, making the return trip across the country, they took us through the southwest. By comparison, that was boring. Coming home, all you could think was "coming home," and the desert lands were seemingly less impressive. So that was my experience with a long train ride. Shirley Houston How many have experienced a summer trip from Philadelphia to Wildwood or Atlantic City on non-electric trains with the windows open and the soot coming in along with the noise? From Philadelphia you had to take the trolley car to the ferry at the foot of Market Street, then ferry across the Delaware River to Camden, and from there you got on your train. You did the same thing in reverse on the way back. When you got to Atlantic City, all you wanted to do was get in the water and feel that ocean breeze. It was a fun thing. Another experience I had was going to New York on the train -a little bit after the war. It was noisy and crowded, filled with exuberant service men coming home from the war. One of them got up and gave me his seat while he stood all the way to New York. It was exciting to be caught up in their enthusiasm - another happy memory of a train ride. Susanna Baum I had a train trip taking my daughter to college in 1992. We boarded the Amtrak Los Angeles to Chicago train in Flagstaff, Arizona. I continued on beyond Chicago to Paoli. The people I met were fabulous. One of the Navajo Indian tribe got on the train in Gallup, New Mexico, and told us about the sights along the way until we arrived at Albuquerque. There was a spot of about 20 miles where there wasn't any scenery of note, so she told us about her father who was a Navajo code talker in World War II. That was really interesting -how a small group left their reservation to join the Marines and use their language to code messages that the Japanese were never able to decipher. And from that trip I began a correspondence with Zonnie Gorman, who was employed by Amtrak, and later met her family. She and her brother, famous Navajo artist R. C. Gorman, made a film about Navajo culture in which they interviewed their father, Carl Gorman, and others who told of their experiences as code talkers in the war and how they devised the code. In 1996 on another trip, coming home from Chicago, I met a Chinese couple behind me. The woman couldn't speak English, but her husband told me they were celebrating a holiday in China where people go visit their family. It was in August. The woman gave me a cake she had made especially for this trip. While we could not talk to each other, we understood the genuine feeling of warmth and friendship between us. Libby Weaver All of my train rides took place during the 1920s, 30s and 40s. We lived at the intersection of Yellow Springs and Mill Roads in Tredyffrin Township in the small green and white house now being remodeled and made into a much larger house. My father was head farmer for Mr. Philip Ten Broeck. When I was between the ages of six and fourteen, my mother and I usually spent a week or ten days in the summer visiting cousins in Brooklyn, New York. Our only means of transportation was a horse and wagon, so my father took us to the Berwyn railroad station. We waited exactly at the spot where Millie Kirkner, Dorothy Hayes and I stood or sat on June 29, 2000, the night of the Berwyn Walk. We probably changed trains in Philadelphia, and went on to Pennsylvania Station in New York. There our cousins met us, and we went to Brooklyn. In the evenings we would walk down, and sit on the stoop at the sidewalk. I was always homesick and wanted to come home early, but we always stayed the planned length of time. It was so noisy. The horses and milk wagons clopped along the brick and cobblestone streets early every morning. I recall grocery shopping, but I don't remember any other shopping trips. We did visit Coney Island, and Rockaway Beach. In 1932, I graduated from Tredyffrin Easttown High School, and in the fall entered Taylor Business School in Philadelphia. For two years I rode the Paoli Local from Paoli to Philadelphia and back each school day. Then in 1942, Wally and I were married in Great Valley Presbyterian Church on the day before Easter. All of my bridesmaids are still living, Mildred Kirkner, Mary Ives, and Esther Yake of Paoli. Raymond Kirkner, also my nephew, is the only usher still living. We could not get gas to go on a trip as it was wartime. The reception was at my mother's home in Paoli, so Raymond drove us to the Paoli railroad station. This was the big ride - on the Broadway Limited to New York - for three whole days. Ray Noll My first train ride was in the cab of a Baldwin locomotive, a 36-inch gauge quarry train. It had worked in a quarry. That was fun. But Eva and I went to the other extreme last summer. I had been reading all the stories about the Chunnel (the train under the English Channel), and we wanted to find out if it was really as fast as they said it was. We got on the train, a very, very fancy thing, streamlined completely, in London. It went through the English countryside, the telephone poles were going by like picket fence. Finally we went through sort of a long train yard where a lot of switching was going on and into the tunnel. We were under the English Channel 30 minutes and then came out the other side. We had gotten on in the center of London and got off in the center of Paris. The whole trip (about 220 miles) was three hours. We had breakfast on the way over, and we had supper on the way home. I followed the construction over the several years it took to build. I'd been in the drilling business, and I was interested in just exactly how they made that tunnel, how they kept the water out. It consists of twin single-track railway tunnels and a central service tunnel for ventilation, maintenance and emergency evacuation. A crossover cavern about halfway over enables trains to switch from one tunnel to the other, if necessary. Construction was aided by "moles" or rotating cutters -- tunnel boring machines -- equipped with laser beam instruments to keep the tunnel digging on course. One little trip. It was very interesting. Herb Fry During the war the railroads were such a big factor in keeping passengers and war materiel moving that, in retrospect, it is difficult to understand completely their rapid demise in the years following. In March of 1937, when President Roosevelt was inaugurated for a second term, Pennsylvania Railroad officials planned for weeks how best to handle the rush of traffic. When it was all over, 68,000 people had traveled between Philadelphia and Washington in one 24-hour period, pulled by the new GG1 electric locomotives. It was a mark thought not to be soon seen again. Then came December 7, 1941. In the wild days that followed, passenger traffic mounted by leaps and bounds. Servicemen traveled to Southern training camps; others came home on furlough. Businessmen rushed to Washington and as promptly rushed home again. Tire and gasoline shortages forced thousands of automobiles off the road and caused their owners to use the rails. On Saturday, April 4, 1942, the day before Easter, 103,430 passengers were carried between Philadelphia and Washington in 24 hours. On the following Monday, the figure rose to 105,856. PRR had accomplished the impossible! Then the "miraculous" began: Friday, July 3, 1942, 110,513; Saturday, September 5, 1942, 137,540; Saturday, February 20, 1943, 141,950; Monday, April 26, 1943, 158,963. PRR officials couldn't sleep. The figures kept mounting until December 24, 1943, when 178,892 passengers were handled. During 1942, an average of 211,763 passengers arrived and departed Pennsylvania Station, New York each day. This was topped in 1943 with a figure of 270,837 a day, and with as many as 900 trains entering or leaving the station every 24 hours. But the movement of armed forces materiel, as well as raw materials, food and finished products, placed an equal burden on the freight train operation. During the peak of the war, as many as 11,000 freight cars passed Gallitzin, west of the Horseshoe Curve, in 24 hours, as the Pennsylvania Railroad System, with its then 9,914 miles of track and 4,500 locomotives, did its part in securing the victory. All this occurred at a time when 38,000 of its employees were serving in the armed services. Sadly for the trains, the great victory effort merely showcased the ability of the U. S. economy to produce goods and services wanted in peacetime by consumers: automobiles, highways, and faster transportation by air. [N.B. The Pennsylvania Railroad statistics are from a column titled "Remember When?" by William G. Dorwart in The Suburban and Wayne Times, December 10, 1987.] |