|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

|

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

|

Source: Spring 2004 Volume 41 Number 2, Pages 56–61 Blacksmiths My presentation is [about] blacksmiths and how people think they should be portrayed compared with how they have actually been shown in paintings and illustrations throughout history.

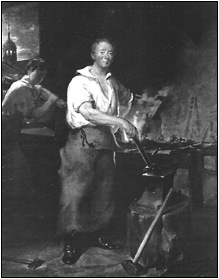

This is Pat Lyon at the forge. This is Philadelphia and this painting was done in 1826 by a man named John Nagle. Nagle means nail or nail maker. Pat Lyon is just the quintessential blacksmith in most people's minds. He's standing at his forge. He's got his anvil and his tools. He has somebody working at the bellows on the left side. Pat was working in Philadelphia at the end of the 18th century. He had been hired to work on the locks of the bank that had just been established. It was actually Carpenter's Hall. It was miserably hot that summer and he was rushing to get the job done. He wanted to get out of Philadelphia because of a yellow fever epidemic, so he was working a lot of hours. He finished the job and left town. Well, coincidentally, the bank was robbed that night, so guess what happened to Pat? He got the blame. I think he was down somewhere in southern Delaware. Word came to him of this, so when he came back to Philadelphia he said, “I didn't do this.” Of course, he was immediately incarcerated in the Walnut Street jail. They suspended habeas corpus. Pat was in jail for some ninety days before they proved that someone else who had been working with him on this rush job for a short amount of time had actually robbed the bank. Later in life when Pat was quite successful he had this painting done. It's more than full size. It is 8 feet tall, and the original, as an insult to the city of Philadelphia, is in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. For most people, this is what they expect a blacksmith to look like. You always have to have someone at the bellows. This young lad at the bellows is probably an apprentice. And that's what blacksmiths look like and that's it. I wanted to see if that was true. So I started reviewing paintings and illustrations of blacksmiths. Most of this work was done at the University of Delaware, by the way. Their library is fantastic, in my view.

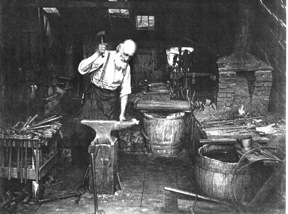

The next painting [on the right] is an older gentleman. Most people don't expect to see that. They expect to see younger people like in the first illustration above. It was painted in 1909 by local artist, Jefferson David Chalfont of Wilmington, Delaware. This painting had been in Los Angeles. I don't know where it is now. See the tool rack and a nice set of tools. What he's using is all laid out. He's a little disheveled though in his shop. He has a lot of tools on his fireplace. He's got a drill press in the back and he's got a nice skylight. Around 1980 I worked at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut with an older retired engineer who did some blacksmith work there. He looked very much like the gentleman in this painting and the shop at Mystic looked like this workshop. It startled me. Quite by accident, at the beginning of the 20th century and the end of the 20th century, you have these two fellows who look so much alike. If you continue looking at illustrations going back in time, what I'm struck with besides the ages of the people shown and the tools they're using, is the number of people. You don't see people working alone in the 19th century, and you don't see people working alone as you go back into the 18th century.

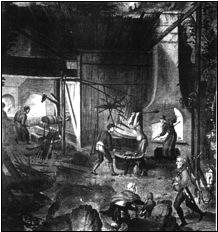

The next painting on the right is a workshop in Sweden. There's quite a bit of heavy work going on. There's four fellows with big hammers. There's something big and heavy being beat out, there's somebody waiting perhaps for their turn to pick up the big hammer, there's someone by the fire either getting warm or thinking about lunch, and you've got somebody with their back turned from the heat. You can't quite see the fire but there's a lot of coal piled up and some body's pulling a big bar—I assume it's an unfinished piece—into the shop. There are lots of sparks. If I could have taken the whole picture, you'd have seen another section where there's people watching the work. It looks like several married couples. There's another whole gang of workers in the back. There's a big heavy red bar and you can just barely make out what they're working on. I can't identify it. So the number of people you see as you go back in time in these shops increases dramatically from what you expect to find. Certainly, if you visit a museum shop or a living history museum today you find one person, perhaps a second person, but in the 18th century, when this is the primary method for producing tools, you find more and more people doing the work.

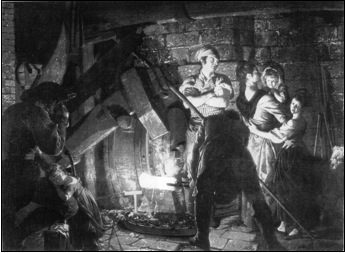

As you continue back in time, the next painting on the right is from the 1770s by an artist you might be familiar with—Joseph Wright of Derby. There's the gentleman in the lower left corner leaning with his hand on the little toddler. And perhaps the other people are married with their children. There's a dog in the lower right corner. The figure leaning over is working on a bloom of iron. What's right about this besides the technical details of the big heavy hammer attached to and powered by a water wheel, the cam, and the drive shaft lifting it, is the color. The artist got the color dead right on the money of what it looks like when you have a bar, big and heavy and hot. Wright is known for choosing an object as the center of the light and then placing all the other objects in shadow the way you see them in this painting.

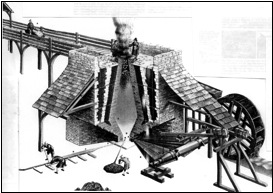

At the end of the 14th century they used the indirect method and blast furnaces for iron-making. If you have been to Cornwall or Hopewell, you may have seen some of the surviving stacks. The one illustrated here is about 30 feet. They're bringing iron ore and charcoal across the bridge and throwing it into the furnace. There's two water-powered bellows and the waterwheel. The hottest temperature here is about 3000 degrees Fahrenheit. The bellows are used to provide the blast for the furnace—they're smelting out the iron ore. When you pour off the slag you get pig iron. That's the same as cast iron. It has that name. When you pour off the troughs, you get these ingots, poured off the center bar in the lower left corner of the illustration. People thought they looked like sows, or piglets, so “pig iron” and cast iron are the same thing; they're synonymous. But you can't hammer cast iron, it has to be refined a second time to make wrought iron. That's what they were doing in the above paintings. They've taken that pig iron and driven off the carbon and they're re-hammering it with these big heavy hammers. This is what was going on here in Pennsylvania. They had these kinds of furnaces. In this part of the country, when they ran out of wood for charcoal, they used coal. The English certainly figured out how to use coal before anybody else. In England they were running out of wood in the 16th century, so they learned how to use all the coal that was so abundant.

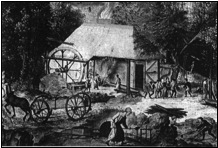

The next painting is from the 16th century and is called “Landscape with Iron Works” by Herri met de Bles. The 2 following illustrations are close-ups from this same painting. Here the same thing is going on. You see, though, that the artist captured more than just the technical operation of the furnace—the blast furnace in the center where they're drawing off the pigs, the refinery forge on the left, and the mining operation in the lower right corner. This kind of huge, almost mythological, painting came to be typical. This is an early example and it is very much accurate. It's not totally mythological—this was the middle of the 16th century. When we get to the 17th century, they start out looking quite accurate. The first close-up is the second painting on the right. It shows the center of the full painting where they have the water power which is connected to the bellows—it's not clear in this picture. The stack is inside the large structure. They're pouring off the long trough. It's the pig iron that has a great deal of carbon in it that's being poured off. They have nice piles of pigs ready to go to market. There's a gang of people carrying off one of the ingots to be weighed. It also shows some mining in the lower right corner. The second close-up is the third painting on the right. It is of the left side of the full painting and shows the second step I was trying to describe. A refinery forge is on the left side of the painting. They've taken the pig iron and put it in here to heat it. They have the water-powered bellows again, and as they heat it and drive off the carbon they get a spongy lump. That's what the fellows are working on in the middle. They're beating that spongy lump into a solid bar. In the operation on the left they take these lumps and hammer them into shape—get them ready to go to market. So there are two steps going on here. The detail in this painting and its close-ups is wonderful for its accuracy. I think if you were to step back in time and go to this place, you'd find that the artist very much captured what was going on. It's typical of the technology of the time—the right state of the art. What you probably haven't seen is what the blacksmith sees when he or she is standing and looking at the fire. I've spent an enormous amount of time reviewing books and reviewing the Internet to see if anyone has even considered trying to capture this. It hasn't been done. When you look at the colors of the fire, you are looking at heating temperatures. You've probably seen oranges at home in fireplaces or in camp-fires. They are 1800 degrees Fahrenheit. With pale yellow and into white fires you are heading towards 2200 to 2500 or 2600 degrees Fahrenheit. The white in the Joseph Wright painting is 3000 degrees Fahrenheit. One of my favorite parts of my work is setting the metal down. I like watching things cool after I finish a job, particularly when I do a big run of something. At the end of the day, I put the last piece of work down and watch some of the different colors go from yellow to orange until it is black. I don't dip it in water. I like to watch it. I do that all the time. When it's cold in the winter and when it gets dark at the end of the day it's a very pleasing sight to watch something cooling down. Are there any questions? Q: Do you ever wear gloves or something to protect your eyes? A: It's pretty unusual to get sparks in your eyes when you're doing this. I know it seems like it should. It's really hard to hold the tools through the gloves. If your tools are slipping through your hands it's even more difficult. You get a few sparks on your hands every now and then, but anyone who's ever cooked bacon at home has had the same experience. Usually it is not enough to make you stop. Q: We visit in Maine and every fisherman has an old anchor dominating the front of his house. They're really old. A: Yes, they're wrought iron and they're all forged. And all of them would have been joined together at the white hot temperature, so not only are they forged but they're made out of more than one piece. In the paintings where they're hammering and stretching out the bars of iron—that's peculiar to this process and you get this grain, if you will, and you can work the grain. It's very specific. The advantages to that, for the most part, if you have iron, are it's going to rust on the outside and seal the inside. That's why some of those things have lasted so long—the material is uneven. The grain is from rusting and the uneven molecules—the molecules that are in there are not pure iron. There's some other impurities in it but for the most part it doesn't have carbon. That's the main thing they try to get out. It's that process of stretching it and hammering down the grain and when you compact it, it makes it very strong even though it's not particularly heavy. It's very strong for its size. Q: Do you wear an apron sometimes? A: Yes. They're really heavier than you would guess. There's a point at which you can't move. It's kind of like sending little kids out in a snowsuit. They can't move. Q: What kind of objects are the most sought after as reproductions today? What kind of orders are you getting? A: Mostly I've produced hardware reproductions for three 17th and 18th century sailing ship replicas—the 1607 Susan Constant at the Jamestown Settlement in Virginia, the 1638 Kalmar Nyckel near the rocks on the Christina River in Wilmington, Delaware, and the 1768 Sultana home ported in Chestertown, Maryland. But mostly it's small things like hinges, latches, and occasionally kitchen utensils. I talked to people about a fireplace crane just yesterday. Things that people can't get any longer that they'd like to have in their homes. I teach a lot of classes and spend some time making presentations. It takes about 6 months of work at the library to prepare. I've spent winter days in the library. It was fun. Q: What kind of consulting work were you doing for the Smithsonian? A: They invited me to review hardware on the sailing yacht, Cleopatra's Barge, that was excavated by the Smithsonian underwater archaeologists. They wanted me to identify objects and parts of objects encrusted in rust and crustaceans, such as a shroud hook. They invited me down for a few days to do that. I get e-mails occasionally. I'll tell you a funny story. I made this very simple mistake when I did this project. In making handouts for students I was looking for drawings. The gentleman I was working with said, “Where'd you get this —what book is it in? I said, “It's in The Ship book.” He said, “It's not in The Ship book.” I was embarrassed because I hadn't made a note of where the drawing had come from. I said, “It's either from The Ship book at the University of Delaware or from the book next to it on the shelf.” So, he went to this shelf and, sure enough, the book next to the book I was talking about is where I got the drawing. Sometimes I can't find things and he said, “Well, we have some books down here. In fact, we have a library that we use occasionally—the Library of Congress.” It's pretty impressive to have lunch in the shadow of the Washington Monument and see the president's helicopter come by; I can tell you that. It made my head turn. Well, I thank you for having me. Kelly Smyth is the blacksmith at the Newlin Grist Mill, 219 South Cheyney Road, Glen Mills, PA 19342. E-mail: ksmyth@newlingristmill.org. This was presented at the January 28, 2004 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. It was transcribed by Bonnie Haughey. |

|