|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 42 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Winter 2005 Volume 42 Number 1, Pages 3–20 SEGREGATION ON THE UPPER MAIN LINE:

For many, the word “segregation” conjures up images of dogs, flames, and violence. Certainly these graphic images of intolerance and hatred would not, in any way, describe the relationships between white and black residents on the Upper Main Line during any period, and in particular within the townships of Tredyffrin and Easttown. Yet, if one could turn back the clock 72 years to the Berwyn of 1932, subtle —and in some cases not so subtle—evidences of segregation and discrimination between the powerful and the weak were common. Across the pedestrian bridge connecting Lancaster and Cassatt Avenues next to the Berwyn railroad station is a structure called “Cassatt Crossing.” Built in 1917, this building was, for many years, the Berwyn Theater. During the 1930s, black and white children would walk together to watch the Saturday afternoon matinees, but the children knew that once they bought their ticket they would be expected to split up during the show. White children were allowed to sit anywhere, but black children were allowed to sit only in the theater's last three rows on the left hand side as they walked in. Farther east, at the Wayne Theater, the only other movie house in this area at that time, blacks were only allowed to sit in the first five rows on the left. And you would never find an incriminating sign to that effect; it was simply the “understanding.” In 1932 you would find no black-owned businesses along the Lincoln Highway, and there was only a single small black-owned business in all of Berwyn. Boy Scout troops would not allow black boys to join them. The meeting halls would not be rented to “people of color,” ultimately forcing the local black community to build the Robinson Wellburn Lodge 794, the Berwyn branch of the Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World near the intersection of Lancaster Avenue and Bridge Street in Berwyn. But despite these “understandings,” the schools of Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships were open to every student in his or her respective township without prejudice to color or nationality. In the early 1930s each grammar school held classes for grades 1 to 8. There were few kindergartens at that time. Students from either township entering 9th grade would attend the then consolidated Tredyffrin Easttown High School, dedicated in February 1909 and located on the southwest corner of present day Conestoga and Howellville Roads.

The Robinson Wellburn Elks Lodge 794, on Lancaster Avenue near Walnut Avenue in Berwyn, operated strictly for people of color for over 70 years.

Wilmer K. Groff came to Berwyn in 1926 as principal of the Easttown Elementary Schools. In 1931 he became the Superintendent for the joint Tredyffrin and Easttown school boards and the Tredyffrin/Easttown High School. The oversight of this arrangement had been cumbersome, with each township having its own elected school board obligated specifically to its taxpayers. Each school board was solely responsible for the administration of the grammar schools within their respective township, although in 1908 the two boards had agreed to join together to administer a consolidated high school. In May of 1931, however, in order to substantially increase the efficiency of the overall administrative process, both school boards voted to place all educational affairs for the two townships under the direction and oversight of a veteran school administrator, Wilmer K. Groff. Mr. Groff's official title was Supervising Principal for Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships.

It was into this social and administrative context that an article appeared in a major suburban newspaper that would change everything. On the front page of the March 10, 1932 Main Line Daily Times, published in Ardmore, was a piece entitled “Townships Will Provide Exclusive Colored School – Tredyffrin-Easttown to Support Institution With Negro Teachers In Charge.” The article informed the reader that plans had just been completed by the joint school boards for “Negro pupils of Tredyffrin and Easttown townships to have their own grade school.” The article continued: According to Norman Joy Greene, president of the Tredyffrin Township school board, the negro school, which is to be taught only by negro teachers, will offer a number of advantages to the colored residents of the community. Easttown and Tredyffrin townships are two of the few townships in the State which have not had colored schools, Mr. Greene explained. This has probably been due to the fact that neither township has heretofore had a sufficiently large negro population. In my opinion, this is the largest step forward that Berwyn has taken in the last 25 years. Our community is one of extreme natural beauty and it is a shame that the building-up process has been stagnated by inadequate schools and the policy of mixing the races therein. In explaining the proposed plan, Mr. Greene, a prominent investment banker from Tredyffrin, who joined the School Board in January 1931, outlined two principal agreements reached by the two boards: Agreement No. 1 – Provides that the two townships will jointly operate a colored school in what is now the comparatively new brick building [a 1912 structure then called the Berwyn Primary School and to be renamed the Lincoln Highway School] now being used by Easttown Township. It is anticipated that the property will be made attractive by the addition of suitable fencing and shrubbery. Teachers will be colored, as will also be the janitor. Experienced educators, with whom Mr. Groff, joint supervising principal, has been in touch, tell us that the colored children progress far more rapidly under colored teachers. It seems that the colored teachers are better able to understand the natures of their children and very often mix with the parents socially and know intimately the home conditions. Mr. Greene described the financial arrangements between the two townships, including proportional rental fees for their use of the brick school building, and that the “expenses of the (colored) school would be divided by the two townships in proportion to the number of their students enrolled.” Agreement No. 1 was to run for three years, beginning July 4, 1932.

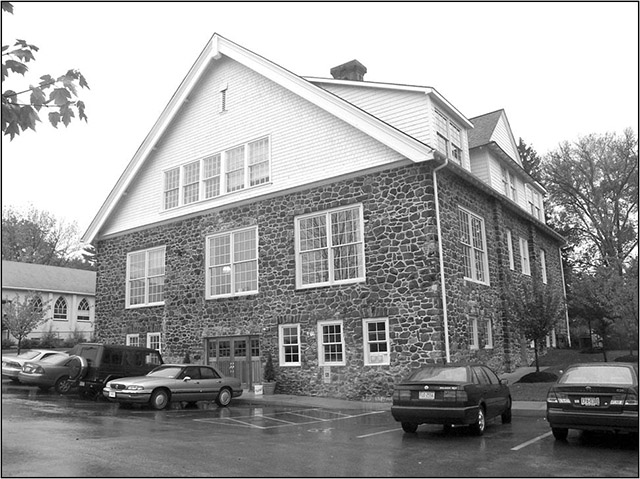

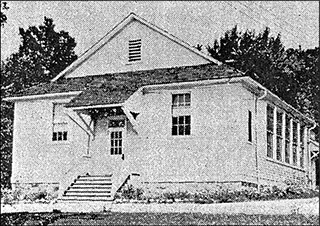

Originally called the Berwyn Primary School, the Lincoln Highway School, built in 1912, was brought out of retirement in 1932 as a blacks-only facility. During the intervening 20 years its condition had deteriorated badly. The Main Line Daily Times article then proceeded to outline Agreement No. 2, in which the Tredyffrin School District would discontinue the use of its old and obsolete North Berwyn

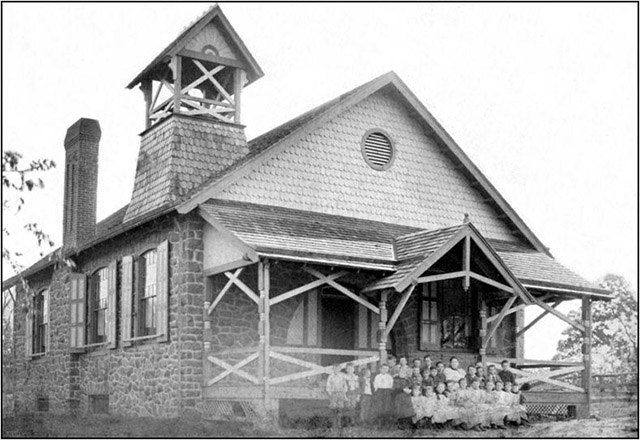

The North Berwyn School was built in 1892 as a one-room schoolhouse on the southeast corner of present day Conestoga and Howellville Roads. Later additions enabled it to operate until 1932, when it was closed to facilitate the agreement between the townships leading to the school board's segregation decision. School—at the southeast corner of Conestoga and Howellville Roads—and send its white grammar school students to the new, state-of-the-art Easttown Elementary School—at the intersection of Bridge Street and First Avenue in Berwyn—then under construction, for a specified fee per pupil, effective for three years beginning July 4, 1932.

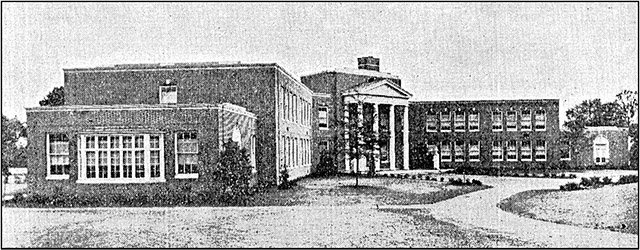

Opened in October 1932, the new whites-only Easttown Elementary School at Bridge Street and First Avenue in Berwyn became a symbol of inequality when compared to the old Lincoln Highway School for black children. Mr. Greene is quoted, saying that the array of advantages of this plan for both townships ...become obvious with a little study. The growth of the two townships has been retarded by the fact that we mix the colored and the white in our schools. Prospective home owners will undoubtedly be attracted to the communities and real estate values should be very much improved. . . . Easttown Township will benefit by being able to open their new school as an all-white school, and their per capita costs will be materially cut down by the fact that Tredyffrin Township will be sending them and paying for more pupils than they will find it necessary to send to the colored school. . . . A colored school in the location of the brick building [at the corner of the Lincoln Highway and Walnut Avenue in Berwyn] will not lower the tone of the neighborhood because the brick building backs up to Walnut Avenue, which is already a colored district. The change will give the colored of the district a fine school with the finest colored teachers, and the best equipment that can be procured. The article ended with the statement that this agreement “has been highly commended by the Business Men's Association and by the Berwyn Civic Association.”

Within hours of the distribution of that Main Line Daily Times on March 10, 1932, disbelief within the black community along the entire Main Line had turned into a firestorm of disappointment and anger, especially from the black parents within the two affected townships. Many of these residents had grown up in the South, had experienced hostile segregation first hand, and had moved, believing they had left segregated schooling behind.

Located next to the Elks Hall, the “APA Hall” was owned by the United American Protestant Association. It was one of the only places in Berwyn where people of color were allowed to hold meetings. The first “school fight” planning meeting was held upstairs. It is presently a nail shop.

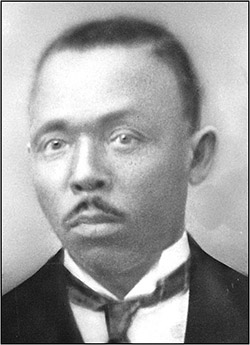

Primus L. Crosby was born in Alabama in 1884, attended Tuskegee Institute, and studied under Booker T. Washington. He came to Pennsylvania in 1918, and his wife Jesseye and twin daughters, Bessie and Essie, joined him later. During the “school fight” he assumed a significant leadership role in local black opposition to segregation. A meeting to plan a several-pronged response to the joint school board's decision took place just days later on the second floor of the United American Protestant Association Hall at the corner of Bridge Street and Lancaster Road in Berwyn. Mr. Primus Crosby, a printer and owner of the only black-owned business in Berwyn, presided over this planning session. By the close of the session a petition had been drafted upon which signatures would be affixed to be taken by a committee of three black Berwyn residents to the Easttown School Board. The first small response to what the black community came to refer to as the “school fight” had been taken. On March 16, 1932, the Main Line Daily Times reports the first mass meeting in Easttown Township to protest the joint school board's decision. Held at the Robinson Wellburn Lodge No. 794 in Berwyn, the meeting was attended by several hundred black residents as well as the leadership from the Bryn Mawr Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. David E. Long, secretary of the Robinson Wellburn Lodge, expressed his opinion that the decision of the school boards “tends not toward the betterment and benefit of the conditions surrounding the negro school children, but rather toward the degradation and segregation.” Mr. Long went on to say that, “the main argument against the proposed new school . . . is that the colored people cannot see why they should be forced to use an old school building no longer wanted by the school board, when they, like the white residents of the same section, have paid taxes to support the building of the new $250,000 grade school in Berwyn.” In the Minutes of the Easttown School District dated April 26, 1932, a notation states: “The president of the Easttown School District received a petition from certain voters of Easttown Township, headed by Primus L. Crosby, Chairman, Harvey Tyre, and Edgar R. Powell, in regard to the school arrangement with Tredyffrin.” On May 5, 1932, ten days after receiving the petition, an entry in the minutes of the Easttown School Board records a response to the black community: After consulting with members of the Tredyffrin and Easttown Boards prior to the meeting, the Easttown School District instructed the Secretary ‘to notify Mr. Primus L. Crosby, Chairman, also Mr. Powell and Mr. Tyre as follows:’ The action of this Board in adopting the plans which you protest was taken only after careful and mature consideration in the sincere belief that ultimately they will work to the best advantage of every pupil. We feel that you should show sufficient confidence in your Board to enable it to make a fair trial of this plan for the three years to which it is committed. Once the plan is in operation your Board believes that the results will prove entirely satisfactory to all our citizens. Relying upon your cooperation, we remain... Also, under the segregation plan, a front page article in the Saturday, May 7, 1932 Main Line Daily Times reported that pupils of the new school would be taught entirely by colored teachers and that the board had announced the receipt of more than 250 applications for the eight positions that were expected to be open.

It is easy to look back at this or any historical event without taking the time to place those decisions and actions within the legal, political, and social context of the time. So let us review the legal footing upon which the Tredyffrin and Easttown school boards, made up of well-educated and astute leaders of their communities, made their decision to segregate the township's elementary schools. Three previous legal actions had laid the seminal framework upon which the local boards made their pivotal school decision. The first of these was an act passed in Pennsylvania on May 8, 1854. Entitled “An Act for the Regulation and Continuance of a System of Education by Common Schools” (Laws of the General Assembly of the State of Pennsylvania Passed at the Session of 1854, No. 610), it created a state-wide system of separate education based on race within public schools and both authorized and required all school districts within the commonwealth “to establish within their respective districts separate schools for Negro and Mulatto children . . . so as to accommodate twenty or more pupils; and wherever such schools shall be established and kept open four months in every year the Directors and Controllers shall not be compelled to admit such pupils into any other schools of the district.” Twenty-seven years later, a second legal action overrode the 1854 act. In 1881, several challenges to segregation in the schools resulted in an amendment to Pennsylvania law making it unlawful for schools or teachers “to make any distinction whatever on account of, or by reason of, the race or color of any pupil or scholar who may be in attendance upon, or seeking admission to, any public or common school maintained wholly or in part under the school laws of this commonwealth.” But a third action, a decision at the national level by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896, overturned any gradual gains in the civil rights of minority citizens. A landmark case, Plessy v. Ferguson, (163 U.S. 537, 1896), ruled by a significant majority of the Court that separate but equal accommodations are permitted under the Constitution. Further, distinctions based upon race did not run contrary to either the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments, two Civil War-era amendments passed to abolish slavery and secure the legal rights of former slaves. Although nowhere in the Court's opinion will one find the phrase "separate but equal,” this ruling allowed legally enforced segregation as long as legal jurisdictions did not allow facilities for blacks to be inferior to those of whites. In the delivery of the Court's opinion, Justice Billings Brown stated: Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane . . . Justice John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky offered the sole dissenting opinion, prophetically stating in part: If evils will result from the commingling of the two races upon public highways established for the benefit of all, they will be infinitely less than those that will surely come from state legislation regulating the enjoyment of civil rights upon the basis of race. We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with a state of law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens, our equals before the law.

Clearly, in light of the overwhelming legal setback on civil rights from the highest court in the land, any chance of a successful legal response by the township's black parents would require a legal resource of substantial influence and tenacity. Not only would such a resource be expensive to working people, but in 1932 there was not a single black attorney licensed to practice at the Chester County Bar. And the president of the Chester County Bar Association, the powerful Colonel A. M. Holding, also acted as chief counsel for the joint school directors. What could the parents do? An initial contact for assistance to the NAACP in Philadelphia proved unhelpful. It is recorded, however, that through an introduction by Mr. C. A. Loeb, owner of a large lumber company in Devon and for whom Primus Crosby also worked, Mr. Crosby was able to meet with the very influential Judge Buck of King of Prussia to explain the dilemma of the black parents. Through Judge Buck's personal introduction, several men including Mr. Crosby and Mr. O. B. Cobb, president of the Bryn Mawr Branch of the NAACP, were invited to Philadelphia to present their case to the well-known attorney, Raymond Pace Alexander, at his office at 1901 Chestnut Street. Formidable talent and influence would be required for the fight ahead, and such strengths were to be found within Alexander's firm. Mr. Alexander was a Philadelphian, born in 1897. He was the first black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School, Class of 1920, and a 1923 graduate of Harvard Law School. By 1932 he had been in private practice for 9 years.

Raymond Pace Alexander was a Philadelphian born in 1897, the first black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, and a 1923 graduate of Harvard Law School. He led the black community's legal response during the “school fight.” Practicing with Mr. Alexander were three young attorneys:

After considering the case facing the black families of Tredyffrin and Easttown, Alexander offered his services pro bono. This offer of diminished fees for the public good was gratefully accepted, and Alexander soon began visiting the black communities in Berwyn and the Mt. Pleasant section of Tredyffrin, establishing trust among families and taking depositions for the fight ahead. The July 2, 1932 Main Line Daily Times reports that “the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People will file suit in the Chester County Courts at West Chester . . . against the proposed exclusive school for negro pupils of Tredyffrin and Easttown townships.” Mr. Alexander is quoted: “The pleadings are under preparation and will be ready during the early part of next week.” Mr. O. B. Cobb, president of the Bryn Mawr Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, called the segregation plan a “great injustice.” He said, “This plan can do only one thing. It will perpetuate race prejudice, something that we have been trying to overcome for the past 60 years.” This litigation would clearly be an uphill legal battle of major consequence. Meanwhile, by the summer of 1932, the new, ultra-modern Easttown Elementary School at First Avenue and Bridge Street in Berwyn had been completed. New furniture had been moved in and the building was ready for occupancy in the fall term starting in September. At both the Mt. Pleasant School on Upper Gulph Road in Tredyffrin—now also designated as a blacks-only school—and the Lincoln Highway School, bids had been accepted for repairs and modifications to these structures. The school board minutes record that: “the school building(s) will be put into first-class condition . . . preparatory to [their] opening in September. This work will be done in line with the recent statement of the board that [these] building(s) will be in the best of repair, on a par with all of the other buildings in the township, when school opens for the fall term."

This school building on Upper Gulph Road in the Mt. Pleasant section at the extreme eastern end of Tredyffrin Township was designated one of the two blacks-only schools during the “school fight” of 1932-34. In August 1932, it is recalled that the joint Tredyffrin-Easttown school board issued official notices to all black parents and guardians in the two townships that their children would be attending schools specially designated for them in Mt. Pleasant and Berwyn. Busing instructions were provided. All during that summer and early fall of 1932—and for the next two years —the old Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church, built in 1861 and located on Berwyn-Baptist Road in Devon, was continually used as a meeting place for the black community.

Built in 1861, the old chapel of the Mount Zion A.M.E. Church on Berwyn-Baptist Road in Devon originally served an African-American enclave known as Quigley Town and acted as a continual meeting place during the “school fight.” It is recalled that the church “served as the place where people would gather together and vote on their actions. It was a natural meeting place, and there were times when you could hardly find a seat. It was a magnet for the black families. Primus Crosby would call a meeting and when he arrived, he often could hardly make his way to the front.”

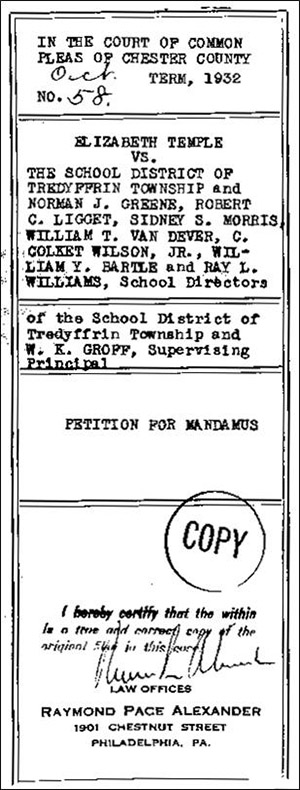

The fall school term of 1932 was scheduled to commence as usual immediately after Labor Day. However, on September 1st, the Tredyffrin School District minutes simply state that due to “the prevalence of infantile paralysis,” both school boards recommend that the opening of school be deferred until further notice —a peek into the days before Dr. Jonas Salk, when even the threat of this incurable disease brought dread to a community. One month later, on Monday, October 3, 1932, the public schools of Tredyffrin and Easttown townships did open. O. B. Cobb's memoir states: “On the opening day of the new semester, both schools intended for Negroes [the Lincoln Highway School in Berwyn and the Mt. Pleasant School in Wayne] were carefully guarded by parents and officers of the NAACP. Most children did not enter, and parents held firm to their resolve to keep their elementary children out of the segregated schools.” The “school fight” had begun in earnest. On the legal front, we have stated that there was not a single black attorney at that time admitted to the Chester County Bar. And no lawyer, white or black, could practice or plead a case in this or any other county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania unless he or she was admitted on motion of an attorney licensed in that particular county. Raymond Pace Alexander and members of his firm had prepared two restraining writs of mandamus against the joint school board decision, and Alexander now personally carried these documents to the Court House in West Chester. Not unexpectedly, the Clerk of the Court of Common Pleas promptly refused to accept them because Alexander was not a member of the Chester County Bar. Alexander attempted to persuade several members of the Chester County Bar to move his admission, but all requests were refused. In his memoir, Alexander recalls, “I took my case to the press, publicizing the inability of a Negro lawyer to even have a ‘just and proper’ complaint filed in court. But one single solitary gentleman of the bar, a [white] former District Attorney of Chester County, came to my support. Thank God for him!”

The writ of mandamus, filed on behalf of Elizabeth Temple, sought to reverse the school board's position on segregation. It was signed by Raymond Pace Alexander and submitted to the Chester County Court of Common Pleas. And so, on October 8, 1932, under the auspices of this heroic former District Attorney, and with Alexander by his side, the two writs of mandamus were filed against the Tredyffrin and Easttown school directors and the supervising principal. “Mandamus,” a Latin term meaning “we command,” is an extraordinary order of the court commanding an official to perform an act that the law recognizes as an absolute duty rather than one for discretion. The two writs of mandamus, filed by Mr. Alexander and the former District Attorney —who remains unknown to this day—were filed on behalf of Harvey Tyre, a resident of Maple Avenue in Berwyn and the father of 11-year-old Lilly Marie Tyre, and Elizabeth Temple, a resident of Centerville - a small community in Tredyffrin Township near the intersection of Swedesford and Devon State Roads, just south of the present Gateway Shopping Center - and the aunt of Priscilla Temple. The first writ alleged that when the new elementary school was erected in Easttown Township, the Tyre girl was not permitted to attend classes there and was forced to attend sessions at the old Lincoln Highway School with only negro pupils. The second writ charged that the same conditions existed in Tredyffrin Township, and that the Temple girl was being compelled to transfer from the new Strafford School to the older and more distant Mt. Pleasant School. Both girls were recorded as “straight A honor students."

An old school at the corner of Upper Gulph and West Valley Roads was replaced in 1930 by the new, larger Strafford School built on a piece of adjoining property. It remained a whites-only school during the “school fight.” It is now the private Woodlynde School. Although the proceedings were initiated on behalf of only two pupils, the wording of each writ indicated that all black pupils within the two school districts were affected by the alleged actions of the school directors in segregating all Negro pupils from schools attended by white pupils. Alexander charged that the two school boards made an agreement whereby “certain” pupils would be sent to separate schools and would not be permitted to enter the new schools in Berwyn and Strafford. The “certain” pupils, he said, were all colored children. In early December 1932 the case was finally argued in the Chester County Court of Common Pleas before Judge Hause, with testimony taken at two hearings. Colonel Holding, representing Mr. Gross and the school directors, argued to quash, or annul, both writs on the basis that the Court of Common Pleas had no jurisdiction in this case. He further argued that the mandamus action should instead have been initiated by the Chester County District Attorney's Office or, preferably, by the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Alexander argued against the motion to quash these injunctions, stating that Colonel Holding's motion was merely taken for the purpose of delaying the final outcome of the case, and that such a delay would work a hardship upon the more than 200 black pupils of the two townships who had received no schooling so far in 1932 as a result of the alleged segregation. The December 6th Coatesville Record records that “while arguments were heard in court on the motion to quash the mandamus writs, upwards of one hundred and fifty colored residents of the school districts were present.” On December 11, 1932, the Chester County Court of Common Pleas, in an opinion signed by Judge Hause, refused to judge the case on its merits and ruled to quash the writs of mandamus. The opinion upheld the contention of Colonel Holding that the mandamus action should be declared invalid on the grounds that the Chester County District Attorney or the state Attorney General must bring such a suit in order to give it proper legal status. Round One of the legal battle had just ended in favor of the school boards.

State Attorney General William A. Schnader refused to become involved in the “school fight” until he needed the black vote because he wanted to be governor of Pennsylvania. He paved the way to end the segregation, but, ironically, lost the vote for governor to George H. Earle in a very close election. Round Two of the legal and increasingly political battle began on February 15, 1933 with a hearing and mandamus application held in the Senate Chamber in Harrisburg before an assistant attorney general of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Raymond Pace Alexander sought to have Attorney General William A. Schnader join the proceedings against the school boards. Colonel Holding argued that the school directors for Easttown and Tredyffrin Townships had, in fact, no power to effect segregation. About one hundred witnesses from Berwyn, who had rented buses to transport them to and from Harrisburg, testified at this proceeding. On March 2nd, hearings were continued in Harrisburg, and testimony by both sides was given before Deputy Attorney General Harris Arnold. Attending with the spectators, which included

Dr. James N. Rule was the Pennsylvania Superintendent of Public Instruction during the period of the Tredyffrin-Easttown segregation case, and applied significant pressure on the joint school board by threatening to cut public funding from Harrisburg. 150 black residents from the two townships, was the Pennsylvania Superintendent of Public Instruction, Dr. James N. Rule. Since school had begun the previous October, no legal attempt had been made by the townships to force the black children to attend their assigned school. On March 9, 1933, the following letter to the Tredyffrin Township School Board was received from Dr. Rule:

Mr. Robert G. Ligget, It has come to my attention that since about the first day of October 1932, your school district has refused or neglected to enforce the compulsory attendance provisions of the school laws in the district, and that as a result a large number of children of compulsory school age in your district have not attended school since that date. Therefore, you are hereby notified that on Monday, March 27, 1933, at 3:50 o'clock, P. M., I will hold a hearing in my office in the Education Building, State Capitol, Harrisburg, at which your Board is required to appear and show cause, if any you have, why the State appropriation allotted to your school district should not be forfeited...

No record exists of a March 27, 1933 meeting or of the “cause” which was requested to be shown. On April 3rd, a more formal letter from Dr. Rule to Mr. Ligget concludes: “it is my duty as Superintendent of Public Instruction to require your district to enforce the attendance of all the children of compulsory attendance age residing within Tredyffrin Township School District and to advise you that a failure to comply within a reasonable time will necessarily mean a withholding of the State appropriation in whole or in part as may be determined advisable.” Obviously, with any local district relying heavily upon the financial assistance of the state, such a letter would have a sobering effect on their school board. During the week of April 9th, notices were sent to all parents and guardians of absent black pupils by the Tredyffrin and Easttown School Boards stating that the state compulsory attendance rules would be enforced. An April 13, 1933 article in the Coatesville Record records that Mr. Alexander was consulted by some of the parents concerning these notices. He is said to have told the parents to disregard the notices and as the days passed these warnings were not heeded. Therefore, beginning on Monday, April 17, 1933, warrants signed by the President of the Joint Board, the Board Secretary, and the Truant Officer of the School Board were distributed to all parents and guardians of absent black pupils. Anticipating trouble from this warrant distribution, a member of the school board had gone to West Chester to confer with the district attorney and the Chester County Sheriff. He requested that additional law enforcement officers be sent to the Lincoln Highway School on April 17th to augment Officer Harry Lewis, Berwyn's only police officer. It is recorded that order was maintained as usual during the period for when the warrants were issued, and that no disruption of any kind was recorded. In May, after months of delay, Attorney General William A. Schnader issued a ruling stating that there were no grounds for his intervention in this issue. Mr. Alexander immediately filed a petition in the Dauphin County Court of Common Pleas in Harrisburg to order Mr. Schnader to join the mandamus action against the boards. Meanwhile, widened community support continued in favor of the black parents. In May the Bryn Mawr and Philadelphia branches of the NAACP sponsored a mass meeting at Union Baptist Church at 19th and Fitzwater Streets in Philadelphia. At the rally, which drew some 2,000 white and black participants, the crowd urged Attorney General Schnader to “join with the Berwyn parents in their fight for basic American principles.” At Mt. Olivet Tabernacle Baptist Church at 42nd and Wallace Streets in Philadelphia, the congregation passed a resolution urging the Attorney General to protect the black parents in the Berwyn district, and forwarded their message to him via telegram. The NAACP even picketed Schnader's home in the Germantown section of Philadelphia in support of the Berwyn parents.

On July 18, 1933, Mr. Norman Greene, the Joint School Board president whose quote in the Main Line Daily Times in March of the previous year had sparked such resentment, and who had been a lightning rod for opponents of segregated schools in the ensuing 16 months, resigned from the Tredyffrin School Board. His resignation, citing “the pressures of my personal affairs,” was accepted by the Board “with regret.” On July 31st, Raymond Pace Alexander participated with several associates in yet another meeting in the office of the Attorney General to seek his support in issuing mandamus. O. B. Cobb's memoir recalls Attorney General Schnader's attitude as "mean and insulting."

Opening day for the new school year in the consolidated districts of Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships was Thursday, September 7, 1933. White and black students alike in grades 9 through 12 registered without incident or apparent prejudice at Tredyffrin Easttown High School. For the many parents and guardians of the black children of grammar school age, however, solidarity with the school boycott continued strong—but not absolute. In order to attend school full time and wishing to avoid the lapse, with no apparent end, in formal education in their own local schools, many black parents had sent their children to live with friends or relatives in adjacent Delaware or Montgomery Counties, or in Philadelphia. Some black children of grammar school age had even been sent to live in New Jersey or Delaware to avoid the ramifications of the “fight.” In the first year of the “school fight,” the Mt. Pleasant School, staffed by principal Miss Mazie Hall and several black teachers, and the Lincoln Highway School, similarly staffed by a core of black educators, had virtually no black children attending classes after the first few days in October 1932. By the start of the 1933-34 school year, all the black teachers and staff had been fired and replaced by white teachers. A trickle of black students were returning to the two segregated schools, but the majority of the black children continued to remain at home without any formal education for a second year. The Coatesville Record reported on October 10, 1933 that out of the 125 children who should be registered at the Mt. Pleasant School, 11 pupils were attending classes. Four of these children lived in Montgomery County and crossed the county line to attend. Four were boarders whose parents lived elsewhere and had been enrolled in the schools by their guardians. The remaining three had parents in Tredyffrin Township. The Coatesville Record also reported “a most peculiar condition existing at the Lincoln Highway School where one 6-year-old girl, Margaret Hill, gets the entire attention of a principal and a teacher each day. This little girl has been placed in school by her guardians, since her parents work as domestics on the Main Line. She is the only pupil in this school where there should be more than 100 children.”

The Salem School, built in 1863 on the western end of Yellow Springs Road, was one of two schools built to replace the Diamond Rock School which closed the same year. At the small, remote Salem School, located on west Yellow Springs Road in the Cedar Hollow area of Tredyffrin Township, black children of mostly quarry workers had traditionally represented one-third of the 60 or so pupils in the student body. During the 1932-33 school year, black children had been barred from attendance at the school. For unexplained reasons, at the beginning of the 1933-34 school year, at least 10 black pupils living in that jurisdiction had enrolled for, and were attending, classes at the Salem School. As the second year of the boycott started, however, no black students attended the Easttown Elementary School, the Strafford School, or the Paoli Elementary School. For the majority of the affected children of grammar school age, the fall of 1933 was the harbinger of yet another year without a formal education, save for those few parents suitably educated themselves to teach their own children, or with the means of finding others to provide an appropriate home school program.

These black children, who could not attend public school classes, were provided with home-school education at the Mt. Zion A.M.E. parsonage in Berwyn.

The Paoli Elementary School, built in 1927, was located on the north side of the railroad at the corner of Fennerton Road and Central Avenue in Paoli. It served as a whites-only school during the “school fight.”

Round Three of the “school fight” began on October 5, 1933 with a protest rally outside the Easttown Elementary School from which black pupils had been barred for over a year. Many of the 225 black pupils of the two townships attended the meeting with their parents. The meeting is both recorded and remembered as being peaceful. As October continued, it appeared probable that a number of black parents would be fined, or jailed for five days in lieu of paying their fine, for failing to send their children to school as ordered. Truant officers from the school district called on each black home asking why the children there were not attending school. They explained that if the children remained truant, the parent would be issued a fine until the child once again returned to classes in his or her segregated school. The fines for violation were $1.00 for the first offense and $2.50 for each subsequent offense; this is equal to $43.00 and $105.00 in 2004 dollars. Two Justices of the Peace, one from Devon and one from Berwyn, instructed Raymond Pace Alexander that they were prepared to carry out their threats of imprisonment under the commonwealth school compulsory attendance law. Alexander was given five days to file an appeal. He announced, however, that he would not appeal the fines, and would delay any further action to determine whether the prison threats would actually be carried out. On October 19, 1933, the first four black men, all from Berwyn, were arrested and transported in handcuffs to the Chester County Prison to begin their 5-day sentences following their refusal to pay a $2.50 fine imposed upon them for failing to send their children to school. They were: Andrew Hearn, his son Virgil Hearn, Walter Harrison, and the Rev. Charles Shepard, lay minister at the Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church in Devon. It was recalled that these four volunteered to lead those still to be jailed, and said of the jailing: “Someone has to go first – let it be us.” Dozens of parents and guardians were fined or jailed, but no individual was jailed more than once. O. B. Cobb recalls in his memoir that, “some paid fines for others. Many, while in prison, were supported by their neighbors.” Raymond Pace Alexander told the black parents that, “when the next person goes to jail, you bring your children. Tell them: ‘I don't have anybody to care for them, and my children must go to jail with me.’ ” It is recorded that one mother with an infant in arms finally broke the jailing cycle. Recollection names this woman as a Mrs. Williams, who refused, on principle, to have her fine paid by the NAACP, and, knowing that her husband would be fired from his job if he did not show up for work, agreed to go to jail in his place so he could keep working to support their family. At this point the court ceased arresting parents. Easttown School District minutes note a proposition unanimously approved on November 14, 1933 by the Joint Board whereby a personal solicitation would be made to have all absentee children in the Tredyffrin and Easttown School Districts return to school by Monday, November 20th. A member of the black community, Mr. Morris Ray, would be appointed "to a Committee who shall pass upon all applications that may be made for reassignment." Further, all pending prosecutions against the parents or guardians of all children returning to their classes by November 20, 1933 shall be suspended during the period necessary "to pass upon any applications for such reassignment." The Joint School Board's plan was found unnaceptable by the local black community and the Bryn Mawr Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and further consideration was refused.

What about the ongoing legal battle to resolve the “school fight.” As Alexander himself describes in his memoir: “. . . for two long years, battling in Chester County, rebuffed; then to Harrisburg to the Attorney General of Pennsylvania for state supported mandamus, then returning to Chester County, back to Harrisburg and innumerable trips – all at night – at least 50 in all – to take testimony in various churches.” The second year of the struggle had turned very political. Pennsylvania Attorney General Schnader had political ambitions - he wanted to occupy the governor's mansion. The second term of Republican governor Gifford Pinchot was due to expire in January 1935, and Schnader wanted the nomination to succeed him. To do that he needed the widest possible support, including the state's black vote. Although Schnader had repeatedly declined to cooperate up to now in the mandamus action, on March 8, 1934 he told a delegation including lawyers and ministers that he would consider their request for assistance to end segregation of black and white children in Berwyn.

With his hat in the gubernatorial ring, Attorney General Schnader now sought a way to favorably settle the segregation case. O. B. Cobb describes how Schnader appointed two Deputy Attorneys General who were to confer with the School Board for the purpose of settling the case. The Bryn Mawr Branch of the NAACP wrote Schnader a letter reminding him of his former negligence and asking him to recall the deputies and to contact the school authorities himself. On March 17, 1934, the following letter was received by the Bryn Mawr Branch of the NAACP:

Dear Mr. Cobb:

William Schnader Forty-four days later, the Berwyn “school fight” was over. The May 1, 1934 Coatesville Record records the end: Tredyffrin township's segregated school controversy ended yesterday when Negro boys and girls and white children attended the same schools. Announcement was made by Raymond Pace Alexander, colored attorney representing the parents of more than 220 Negro children who refused to attend schools specially designated for them, that the joint school boards of Easttown and Tredyffrin townships had notified him yesterday that the segregated system would be done away with at once. Alexander, in turn, sent notice to the parents that they should send their children to school yesterday morning, and a check up showed that nearly all of the parents had complied. It was the first time since June 1932, that the Negro and white children in the two townships were in the same school buildings. In Tredyffrin township they were attending Mt. Pleasant School, and for the first time since the new Berwyn School was built in Easttown township, white and Negro children were in the same classes yesterday morning. The old Berwyn School, on Lancaster Pike... was closed yesterday and will remain closed for the remainder of the term.

The struggle for equality of education had finally ended successfully. It is reported that in the remaining month of the 1933-34 school year, the approximately 225 black pupils reported to their nearest grammar school to be reintegrated with the rest of their class and grade. Over the seven decades since that time, participants remember the crowded classrooms during that final month of classes, and nothing but kindness on the part of both teachers and pupils as former classmates were reunited. By the following September, at the start of the 1934-35 school year, class balancing had been completed and normalcy had returned. The price of victory had been high, leaving casualties from the struggle. Many black children, whose parents were without the means to provide suitable and ongoing education during the two-year boycott, had fallen behind academically, requiring them to leave their old classmates and be reassigned to another grade. As happened to many, a student scheduled to enter the third grade in 1932 would now be obligated to enter the third grade in 1934 even though the child was two years older than his or her classmates. Children can be cruel about such things, and those insults are recalled over the decades. Of particular concern, were students who would have entered 7th or 8th grade in 1932, and who would now be forced to catch up academically in the grammar schools even though they had grown to near-adulthood physically. Many individuals recalled leaving school permanently rather than face taunts of alleged retardation. Furthermore, because the case had been settled on BOTH legal and political fronts rather than solely within the court's jurisdiction, no clear precedent had been established for others to follow. When a group of black parents sued the Chester, Pennsylvania, School Board for maintaining segregated high schools, the school board retaliated by failing to renew the contracts of 50 black teachers. School segregation remained pervasive in much of Pennsylvania well into the 1940s. In 1948 the NAACP conducted an extensive survey of school segregation in the state, and found that more than a quarter of the surveyed school districts maintained some form of formal separation between black and white students. They had either segregated schools or segregated classes within schools. The towns of Chester and West Chester continued to operate all-black elementary schools. Willistown Township, Downingtown, and Kennett Square continued to operate segregated classrooms within integrated schools, with black teachers teaching only black children. In some of these segregated classrooms, black children of various ages and ability were combined in a single room, called a “union room,” resulting in an educational experience not only separate but inferior to that offered to white students. It would be another 20 years until the case of Brown v. Board of Education was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954, and the "separate but equal" doctrine previously adopted in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson was unanimously struck down and found to have no place in public education. Chief Justice Earl Warren, reading the decision of the unanimous Court on May 17, 1954, underscored that segregation of children in public schools based solely on race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. The Court's decision was a major step toward complete desegregation of public schools. And yet, two decades before this sweeping decision from the highest court in the land, a lawyer of uncommon brilliance, and hundreds of brave, local men, women, and children acted upon their conviction that a line had been crossed, and started a “fight” that served as a precedent of what could be done when equality was compromised. Editor's note: On 22 April 2024, minor revisions were made to the last paragraph on page 17 at the author's request.

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS INVOLVED IN THE “SCHOOL FIGHT”

In preparing this narrative I received extraordinary assistance from many individuals to whom I wish to express my sincere gratitude for their ideas, information, and encouragement during the research of this seminal, yet little-known, civil rights struggle:

I also wish to thank members of the Tredyffrin/Easttown School District, and members of the School Board, including, but not limited to, Dr. Peter Motel, Mrs. Liane Davis, Dr. Dan Waters, Dr. Mary Lou Folts, and Mrs. Nancy Letts. Thank you for your interest and guidance.

Davison M. Douglas. “The Limits of Law in Accomplishing Racial Change: School Segregation in the Pre-Brown North.” UCLA Law Review, vol. 44, no. 3 (February 1997). p. 727-28. Joseph H. Rainey. “Segregation Ends in Public Schools of Two Townships.” Philadelphia Record, May 1, 1934. Raymond Pace Alexander. “Outline of the School Situation in Easttown and Tredyffrin Townships” (October 18, 1933). NAACP Papers, Box 1-D-48, Library of Congress. Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, Race Relations Committee. Minutes for 1929-36. Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Easttown School District. Minutes for May 5, 1932 through June 14, 1934. Tredyffrin School District. Minutes for January 29, 1931 through September 25, 1934. Tredyffrin Easttown History Club, Berwyn, Pennsylvania. Newspaper clipping files. Frederick Douglass Institute, West Chester University, West Chester, Pennsylvania. Newspaper clipping files. Robert L. Ward. “Public Schools of Easttown and Tredyffrin Townships – Part II.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 3, (July 1997). pp. 81-96. A Short Summary of the Life and Activities of Raymond Pace Alexander. (Judge, Common Pleas Court #4, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). May 1966. Paper provided to the author by Mr. Robert Wright. Oscar Bullock Cobb. A Brief History Of The Bryn Mawr, Pa . Branch Of The National Association For The Advancement Of Colored People. Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, 1934. Paper provided to the author by Mr. Robert Wright. Chester County Court of Common Pleas. Legal documents filed with the court pertaining to the “school fight.” Provided for review by the author by the Tredyffrin/Easttown School District. Main Line Daily Times. Various issues for the period March to July 1932. Microfilm collection, Free Library of Philadelphia. Lisa Cozzens. “Brown v. Board of Education.” African American History. 1995. http://fledge.watson.org/~lisa/blackhistory/early-civilrights/brown.html Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). http://www.nationalcenter.org/brown.html U.S. Department of State. Basic Readings in U.S. Democracy. Introduction to the Court Opinion of the Plessy v. Ferguson Case. http://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/democrac/33.htm Roger Thorne, a retired executive for an international services company, became president of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club in 2003. A May 2004 Philadelphia Inquirer article first exposed Thorne to the “Berwyn school fight,” and provided the catalyst to pursue the details and context of this little-known event in our local past. This talk was presented at the October 24, 2004 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Page last updated: 2024-04-22 at 15:29 EDT |