|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 42 |

||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Summer 2005 Volume 42 Number 3, Pages 82–94 MAPPING THE MAIN LINE

Hint for using the footnote reference links: Using the “Back” feature of your browser will return to the previous [Note] link location after you read the footnote. The Delete (Mac OS) or Back Space (Windows) keys often perform this function.

My dad started the Franklin Survey Company in 1928. He was first going to name it the Lincoln Map Company but changed his mind. Because of Ben Franklin, he named it Franklin Survey. The name is a little wrong in that we didn't do any surveying—we didn't have engineers—we had people doing map drafting and research. At a later date, before we moved from Philadelphia out to King of Prussia in 1986, I changed the name to Franklin Maps. My dad was a little upset, but I reminded him that he always answered the phones as "Franklin Maps" and that's why I changed it.

In the beginning—before my time—the business was publishing some atlases, basically in the Philadelphia area. My dad made a 1933/1934 Chester County, Volume 1 & 2 [Note 1] and a Main Line atlas, which included Lower Merion, Radnor, and Haverford. We now call it Main Line Volume I [Note 2]—at that point volume two wasn't planned. The first atlas he did of Lower Merion, Radnor, and Haverford was in 1937. He did a revision of the first volume in 1948 [Note 3]. In 1950 he did Main Line Volume 2 [Note 4].

He did some other areas: Lower Fairfield County in 1938, one over in Hamilton, New Jersey in the 1930s and revised in the 1940s. He produced 5 volumes for other parts of Montgomery County—the northern suburbs, four of them in the 1930s and a repeat of one in 1949. My dad produced a fair number of atlases in this general area, including ones for Wilmington and Atlantic City. He expanded to other parts of the country—as far as Florida. He also did local street maps in this area—Main Line, Upper Main Line, Old York Road, and other areas. He started in 1928 and then came the depression years. Now people come to the store and want to buy a sheet from an atlas of this period. There weren't that many made at that time. When they don't understand why, I explain that my father didn't have the money then to print any extra sheets just to have them sit around. Then came World War II and he had no employees because they were all off at war. In 1943, the G. M. Hopkins Co., also in Philadelphia, was up for sale. They produced a tremendous quantity of atlases in many areas of eastern United States. My dad wanted to buy it but the business had been sold to four employees with a note that they had to pay back Thomas' (I believe the owner's name at that time was Thomas) church $25,000. They didn't have the money. They didn't want to take the chance. My father put in an offer and bought the G. M. Hopkins Co. I'm not exactly sure of the price—it was somewhere between $1,400 and $1,500. He did not have to put up $25,000. They took whatever they could get. Map businesses at that time were not doing well. It was a tough time.

Atlases were being produced by many publishers in different parts of the United States and many of them were done for this area. A lot were produced, particularly in the centennial year of 1876, of different counties. All but 10 or 11 counties were done at some point for Pennsylvania. These atlases didn't have a lot of information on the individual plates because the areas weren't usually developed yet. They were a lot like Witmer's Chester County atlas [Note 5]—they would have detailed information on a borough or city for lot lines and properties. But when they did rural townships, the plates had a survey of the township and some of the owners names placed on the maps without property lines. The first book I know of that was different, at least in this area, was an 1881 atlas by Hopkins—Bryn Mawr and Vicinity [Note 6]. It covered one and a half miles on either side of the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks, an area originally considered the Main Line. It was a narrow stretch. The people from Gladwyne aren't very happy when I tell them they're not on the original Main Line. They're past it by a mile and a half. In the early 1900s we start to see more atlases produced for the Main Line suburban areas. Atlases were entitled farm atlases, real estate atlases, plat books. The ones around here, in many cases, were called railroad atlases. They're all pretty much the same thing. One is titled Property Atlas: Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad from Overbrook to Paoli [Note 7]. The Pennsylvania Railroad had nothing to do with producing these atlases. Instead, the publishers traded in on the recognition of the name of the railroad to sell their books. Here's a story. A fancy Main-Liner had a party. The people who came by rail were a half hour later arriving than the “scheduled” time. The host, upset, called the owner of the railroad, A. J. Cassatt. Mr. Cassatt promised it would never happen again. The next day, he took care of it—he took the train station down.

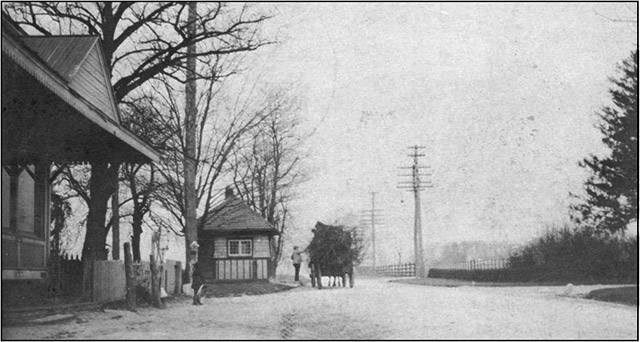

Paoli tollhouse at the intersection of present day Routes 30 and 252. Lucy Sampson, photographer, c. 1900. Chester County Post Card Album 1900-1930. William C. Baldwin, Paul A. Rodebaugh, editors. West Chester, 1980. The people who owned the railroad also owned the Lancaster Turnpike with the tollhouses. Maybe you've seen pictures or postcards of the tollhouses. The idea was to keep the turnpike tolls high so people would use the railroad. The Lower Merion Historical Society asked me to scan a poster that a member found in a frame behind a picture. I scanned it and printed it and we now have a very large poster showing the prices of the tolls on the turnpike in probably the early 1900s. If you translate these prices into today's terms and totaled all of them for one day, you could probably clear the debt of two or three townships in the area. For example, here's one of 67 cents. The green ink figures on the poster are charges for automobiles carrying six or more and less than twenty persons. Automobiles carrying more than 20 persons were charged double. Black ink figures are charges for automobiles carrying two persons, red ink figures for automobiles carrying four persons only. All the stops on there, all the way through. It gives you an idea of how many toll stops they had on Lancaster Avenue. That's what Cassatt was doing. If the atlases had been supported by the railroad, there would have been advertisements or information indicating that the Pennsylvania Railroad backed them. There aren't any. One other thing about the names of these atlases as Pennsylvania Railroad atlases. When a lot of the atlases were published originally, they covered counties. In this area, when you followed the railroad out to do an atlas—because that's where the influence was—it covered parts of three counties – Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware Counties. How would you name the atlas? Publishers came up with the Pennsylvania Railroad and listing the stations. In other words, the influence of the atlas was really where the railroad went. It had nothing to do with the railroad but it was a method to give the baby a name. There's an atlas published by Klinge in 1927 for the Reading Main Line [Note 8]. The Reading Railroad, which had tracks going north of Philadelphia on the east side of the Schuylkill River, also tried to trade in on the phrase “Main Line,” but it never caught on. The Pennsylvania Railroad just built the railroad and then Mueller made his 1908 atlas and said, “That's the area I'm covering. It's the best way I can title it, instead of saying ‘parts of' the different counties.” The 1908 Mueller atlas states it is “Indebted for hardy and most generous assistance to the local engineers, surveyors, public officials, and private citizens, as well as our public spirited patrons who have contributed for their liberal support to the publication of the Main Line Atlas. The publisher most respectfully dedicates this work to their use.” There is no mention of the railroad at all. At the end of the 19th century, Philadelphia was the center for making county atlases. That's one reason why there so many of these for all or part of Chester County. I'll go over some of these for you. Witmer's 1873 atlas covers all of Chester County.

Hopkins' 1881 Bryn Mawr and Vicinity Covers a very small portion of the pan handle of Tredyffrin Township. Breou's 1883 Farm Atlas [Note 9] was one of the first ones. What we love about Breou is that they counted the backs as pages, too. A lot of atlases did that, i.e., counted the in-between pages. All the plates have property lines on them, while the 1873 Witmer did not. The Breou has more detail and more information.

It took a lot longer to survey and get plot plans and to show who actually owned the property. This is a big change in this atlas that the some of the other earlier ones didn't have. J. L. Smith 1887 Overbrook to Malvern Station [Note 10]. His was the Philadelphia map store I ended up purchasing. I don't think Smith really did that much with the drafting of the maps because this atlas has G. Wm. Baist's name on it as the topographical engineer. Because Smith had a map store, he somehow became the publisher of it and helped to get it started. Smith also did an Overbrook to Malvern in 1900 [Note 11]. In this one the topographical engineer is given as E. [Elvino] V. Smith. Mueller produced many of the early atlases and did some of the nicest work around: Rosemont to West Chester 1897 [Note 12], Overbrook to Paoli 1908, Devon to Downingtown and West Chester 1912 [Note 13], Overbrook to Paoli 1913 [Note 14], Overbrook to Paoli 1920 [Note 15].

Bromley did a 1926 Overbrook to Paoli [Note 16].

Franklin Survey continued producing Main Line real estate atlases after Mueller and Hopkins: Chester County Volume One 1933 and Chester County Volume Two 1934—volume 3 or 4 were planned, but never done—Main Line Two 1950 which also included Newtown Township, Main Line Two 1963 [Note 17], Chester County Volume A 1969 [Note 18], and Main Line Volume Two 1984 [Note 19]. This was the last real estate atlas produced for the area and it was a Franklin Survey atlas.

How were these atlases made? Some questions I can answer, some things I can show you, and some things I'd have to guess at because I'm still not old enough to go all the way back. A lot of time and man hours were spent in researching, drafting, and assembling an atlas. When we moved from Philadelphia to King of Prussia, anything in this part of the business was dying at that point. My father had bought the Hopkins Co. and rehired an employee he had known that was with Hopkins. That employee spent time working on getting field sheets and information ready. Drafting and putting together these preliminary sheets with the owners' names, the subdivision plan names, and whatever else they needed was just the start. I have a sheet that lists a number of subdivision plans that were gone through and looked at, so they spent a lot of time plotting. This is just a beginning stage. I have a sheet of some fieldwork that shows how it was done, first it was penciled in, then it was inked in, and then it was drafted. So the work was done twice. When you go out to field check an atlas, you drive it or walk it, depending upon the situation; you pencil in the sketch of the building, the construction material, the house number, any stables or barns—which later became garages. Then you inked it. Then you put a piece of mylar on top of the inked copy and drafted the atlas, tracing the lines from the bottom inked copy onto the mylar. Here's an original drafting showing part of Tredyffrin Township from the Main Line Atlas, Volume 2, 1963. This is linen, it's a material that's got a starch in it. To draft it, one person did the line work. Another draftsman added the large lettering. To do this, you either had to have a very good eye or space it out with pencil lines, then erase them later, so as to have the right balance as to the where the name was. This isn't “put it on a computer and move it here or stretch it out.” This is by hand, once you get the first letter down, the others have to follow behind —it's all got to fit. Then with a very fine pen, you do the fine lettering, which includes dimensions, house numbers, etc. If the scale was 200 feet to the inch it was easy to draft. If it was 400 feet to the inch, it would be very tight and time consuming. From this original drafting the basic atlas sheets were printed. We used photo offset. A film negative of the drafted atlas sheet was made. We didn't do this, we sent them out. Then it would be stripped up so that you could then plate it. Then we printed it on whatever grade paper we decided to use and in whatever quantity was needed. We used 50% rag paper. We probably printed 150 copies of the Main Line, Volume Two 1963 atlas. After printing, comes coloring. At the same time as the basic atlas sheets were printed in black ink, 5 or 6 or 7 other sheets were printed and then varnished—probably with a couple of coats. The varnished sheets were the stencils. After the varnish dried, you cut out all the areas on one that you wanted to be the same color, i.e. blue buildings all on one stencil, red buildings all on another, yellow on another, green on another, and so on. Streets had to be cut out on 2 stencils because if you cut the entire street out on one, everything would fall out. So you cut part of a street on one stencil and the rest on another stencil. After the stencils were cut the basic atlas sheets were water colored. We didn't do this directly. We had someone named Harry Kahn that my father used to fight with. He'd say, “Harry, you charged me more to color 100 sheets than you do for 125.” Here is a set of pans and brushes used for coloring I found upstairs. These are the actual brushes that they used to color the atlases. You'd color one sheet, put it aside, do the next sheet, put it aside, and on and on, going through that process for every color on every sheet.

Courtesy Franklin Maps Red represented brick buildings. Yellow was for frame buildings. Blue was for stone. There may have even been brown for stucco. So that would be four colors for the buildings. In some cases, you tinted out the different subdivision plans using blue, yellow or pink for that, so that's 7. Green areas would be 8. Water would [be] 9. The streets had to be done twice. So you can easily see that each sheet had to be handled about 10 different times just to color it—a long process. Sometimes you can see the actual brush strokes on the atlases. It wasn't perfect—a little overlap, a little “underlap.” Spots were missed. Color separations used in later printing methods on printing presses also used this same basic principle of a separate printing for each color. Now the atlas would be bound. Most of the volumes were bound, up until the late 1940s, with hand sewn bindings. The Breou is hand sewn. I've got plenty that were hand sewn. My dad did one book in 1942 with a post binding, Upper Darby & Vicinity [Note 20]. But he went back in 1948 and did the Main Line Atlas Volume 1 with a hand sewn binding. I believe that was the last one. After that, they used what was called the Chicago Post, whereby you could actually take a sheet out of the book. That started in about 1950. There was a company in town that used to mount these sheets on linen or muslin to give them more strength and backing. When Bill Andrews was in the real estate business, he would buy the linen books because he knew they would hold up better. When the Main Line Atlas Volumes 1 or 2 were published, they would have each cost $275, or $325 if they were on linen. I don't know what we paid to have it mounted on linen, but if you wanted it mounted on linen today, you'd probably spend $25 or $30 per sheet.

The price didn't include an updating service. We would make a book and then put revision stickers in it. One way to make the revision was to make a drafting on a piece of linen of all the different little pieces of all the changes. The revision sheet was printed on a 17” x 22” piece of paper with a glue backing. We'd take these to a couple of women in New Jersey, who'd pin two sheets together, one on top of another, cut each revision out, and put all the copies of the stickers representing each revision in a blank book with so many pages in it so that in the end you'd have all the stickers together that were to go on page 1, page 2, etc. of an atlas. We'd go out, pick up the atlases, and bring them back here. We'd line them up, wet the atlas—not the sticker—and use a binder's bone to push the sticker down. If you look at these pages through the light, you can see how many revision stickers a page had. You can see where it's darker. The Sanborn Company did it a little bit differently. Sanborn made fire insurance atlases. These were at a much larger scale. The company and its atlases were only interested in buildings. They didn't care how the sticker fit in. They just slapped it down. We had to be more careful and concerned because if you stuck a revision down and the first one was off a little bit, and then you had another revision the next year, you might cover up something here and there. Sanborn used to do its revisions by sending ladies out to where the books were located. They'd paste the revisions down real quick because they didn't care if they covered up the lot line—they just wanted to get the building revision stuck down on the atlas sheet. If you think our books were heavyweight paper, the original pages in the Sanborns were like heavy cardboard. By the time you'd wet the pages enough to get all the stickers on they would become wavy and not lay flat.

Drafting our real estate atlases was a long and involved process. To do field research in my day and age—the 1960s and 70s—we'd drive either with one person or two, if we were lucky. The rider would sketch all the buildings in by eye. It cost so much time and money to do this, that today, with the merger of real estate offices, you're not going to see anybody doing anything like that again. We stopped producing real estate atlases in 1984. My father had started producing sheet maps of streets—these are very different from real estate atlases—in the 1940s and 1950s. Now street maps are our main product and we do them as both folded sheets and atlases. If you wanted something similar to the real estate atlases after 1984, you probably checked with your local township office. Some local planning agencies are willing to cooperate with mapmakers. Others are not. In preparing our street maps and atlases I've gotten good cooperation from Lebanon and Luzerne Counties. Many government agencies revised their emergency planning mapping after 9/11. If you ask Montgomery County, for example, for house number or other information that may have been remapped as a result of 9/11, they don't help. They feel they've spent money on it and they're not going to give it to you. They don't care if you have the name right or wrong or whatever. Today, the information is all out there. It is on the Internet. The real estate atlases had a tremendous amount of use. I have one 1937 Atlas of the Main Line of the area down around the Haverford School from the McMullin and McMullin realtor office. They wrote in all of the dates, and prices, and names of people that were buying individual properties. This was before the multiple listing service—this was their multiple listing book. I bought a house in Merion Park from the original owner and the realtors have the date that he bought it and his name and what he paid for it. There's these long lists of this type of information all over the whole book. It's unbelievable. Our atlases got a tremendous amount of use from appraisers, from engineers, and from others, including a few banks in the area. By the 1960s and 70s the atlases only had maybe 60 or 70 customers, maybe 75 if you were lucky, that actually had the books and kept them up to date. At a later date I changed from selling them to leasing them because that way we knew we were going to get the sale of the revisions. Otherwise, we weren't sure of that. Our atlases were for real estate brokers, real estate appraisers, and mortgage companies. Title insurance companies were heavy users of them. They would buy the atlas. There wasn't anything in the way of sponsorship of either the real estate atlases or the fire insurance atlases. The Sanborn atlases were almost totally for fire insurance. Sanborn was a big company and is still in existence today. The insurance companies would buy their fire insurance atlases to look at their properties, then split the atlas up or do whatever they wanted with them. On those atlases, the scale is larger and there is a lot more detail, but the detail and interest is on the building. On ours, although the detail and interest on the building was there, it is more on the land and the ownership of the land and what was around it and who could grab what piece of property for subdivision or how it could be appraised. On the Sanborns the buildings were all labeled. They would show how many stories there were, the construction type, detailed drawings of individual buildings with the scale around 20 feet to 50 feet to the inch where ours ran basically 200 feet to the inch. That‘s a big difference and there's a total difference in the usage of it. The only customer of ours that I know of that purchased both is the Free Library of Philadelphia. I can't think of a builder or broker or bank or title company that was interested in a Sanborn atlas.

We got a call or an e-mail the other day: “I have your atlas and I built that subdivision and I named the street after my wife and her name is Lorraine and you've misspelled it on your map. You only have one ‘r'.” So I checked. The post office has two “r”s. The Delaware County website and tax assessment office has two “r”s. I looked at MapQuest, MSN and Yahoo and they all have two “r”s. We run into that. The name on a street sign might be spelled one way and the official records spell it another way. I did a 2002 street atlas of Schuylkill County and one woman didn't want to talk to me because my map had one thing, and the local agency map prepared after 9/11 had another. In Pennsylvania, the townships have a lot of authority and if you want to try to get a street name changed, you have to start at the township and go through the county. They can put the pressure on, but you can't always get them to change it. There are always mistakes on maps. In our restroom, we hung up a map with an error on it to remind us that we can make mistakes. Others do too. A while back I was driving up to Morris County, New Jersey, because we did an atlas up there. I looked at the map and at a major intersection – it might be 78 and 287 – it's been around for thirty-some years. The map said Exit 30 and the sign said Exit 29. I e-mailed the state. They e-mailed back and said, “Yeah. We dug into it and you're right. We've had it wrong since 1972. The maps are right. The signage is wrong. We're going to change it one of these days, but we have to write the township, advertise it, put up new signage saying ‘formerly Exit 29' ...” A trap is a street or other feature on a map that doesn't officially exist. A map publisher may put them in to try to catch other publishers violating his copyright. It doesn't always win copyright cases. There's a U.S. Supreme Court case called Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. (499 U.S. 340, 1991). Feist basically says you cannot copyright facts and therefore you cannot copyright non-facts. A non-fact in and of itself is not an infringement of copyright. Somebody had a list of attorneys in the south and had put in a few that were not attorneys and somebody copied the list. This case went up to the U.S. Supreme Court and they decided you can't copyright facts—which is understandable—but you can't copyright non-facts either. Trap streets are not facts, so, yes, you can put them on maps. It's a fake street. ADC [formerly Alexandria Drafting Company] put a church on the wrong side of the street once. Was it a trap? No, I don't think so. It was a mistake. There's a difference between a trap and a mistake. You don't want to put anything on a map that you know is incorrect. If you put a feature on a map that isn't really there, that's probably a trap. But if you put something in the wrong place, that's an error.

Q: What about wall maps? Do you sell many of them? Are there many around? A: No. The problem with large wall maps is that they are so big that to handle and sell them today is unbelievably difficult. Most were produced on a heavy material and mounted with sticks on the top and bottom. They were rolled up and in many cases they were varnished. Their condition is tough and when you display them, you lose a whole wall. They're worth a lot of money if you can find a buyer. One of the first county atlases was taken from a huge wall map of the county. They cut around the shapes of the townships and pasted the pieces onto another backing. They cut the townships out and pasted them into the atlas from a wall map. Lancaster County was done this way three times in 1864, 1875, and 1899. There were three of them. I have all three. Q: We have one wall map 6' by 8'. It's in great shape, has been covered by glass, and is undiminished in its clarity. Would it have any market value? A: Yes, probably between $2,000 and $5,000. Maybe higher. But you have to find someone who wants it. Q: We were going to put it on eBay. Comment: this is our version of Antiques Roadshow. Q: What type of person would be interested in getting into this line of work? Scholastically, what would they take up? Were they printers or were they artists. What would they study to get into something so detailed? A: I doubt they were artists or printers because all they did was drafting. Honestly, by today's standards, it would be boring. I probably have a ruling pen around. A ruling pen is a difficult instrument to use just to draw the lines. There's two little nibs, you screw it together, dip it, wipe the ink off the edges, then to get it to run you run it along your finger, then you draw your lines. The lot lines are pretty thin lines. With thicker lines, you have to make sure it doesn't spill over. It was just somebody who wanted a job as far as drafting is concerned. My father was not brought up in the production part of the business. He started in mapping by doing sales. He would sell maps or wall maps or atlases, then he would get someone else to do the drafting of the atlases. He didn't know as much about that as I did. Q: Where would somebody get the training? A: The G. M. Hopkins Co. was started in 1865 so the training was passed on from generation to generation. It wasn't something you went to school for. It was something where you went out and got a job and became an apprentice the way you would if you were making shoes or blacksmithing or whatever it was. You learned from the prior generation. Q: Do you have any descendants coming into the business? A: My son's in the business but I don't think he'll apprentice to that part of it. Maybe one of my two grandsons or my granddaughter will be the apprentice. They're very good on the computer. Hopefully I can wait and will make it for 20 more years and be able to train somebody. Q: When did computer methods start to take over? A: I can't speak for everybody—National Geographic started in 1989— but at one point we were doing drafting with ink and pen, then at a later date we started to do scribing, then scribing gave way to computerized mapping, which we started doing in 1992 or 1993. It's changed everything, how the whole business operates, what direction we're going in, how we're doing things. Q: Is there still a great demand for the old atlases? A: Yes, there is a demand for them which we sort of create. Except for a couple that may be an original here and there, most of the ones up on the walls here are reproductions; I scan them in, correct or do what I have to do in Photoshop, and print them out on a canvas material with a pigmented ink. We do our own framing. At this point, we only sell the reproductions framed and that's probably the way it's going to stay. The one you're sitting next to is based on the 1881 Hopkins Bryn Mawr atlas but you can't find that plate in the original atlas because I've added in parts from the 1920 Mueller atlas. I put four plates together in the computer. It needed a little touch-up in a few spots here and there, but Wayne is a popular area so I thought I would try it. They were scanned in at 300 dots per inch (dpi) and combined into one map. That one file is probably close to a half a gigabyte of memory on the computer. Q: Is this the resort development of North Wayne? A: Yes, that was a summer resort at one point. Of all the atlases that have really detailed information of property owners and limits, the 1881 Hopkins atlas is probably one of the earliest. It is the oldest atlas of the suburban Philadelphia area on a large scale. Our old printing presses are in the back. One, from the 1950s or 1960s, is from Zable Brothers and is in the pressroom. We do the printing of our up-to-date maps on those old pieces of equipment because I don't have the money to buy a new press. My scanner's at home. It's a little more than 36” of usable glass. There's a slit of about 1½” in width that the piece feeds through. I scan the atlases at anywhere from 125 to 300 dpi. A normal atlas page is 32-35 megabytes. If you scan at more than the 300 dpi level, your memory requirements go way up. So most of my stuff is on external hard drives with backup on external hard drives. I have 300 gigabyte hard drives and I wish they made 500 gigabyte hard drives. Q: Will a 1995 or 2000 atlas be available in 2010 or 2020 in hard copy format for people to look at? Will this be stored in some kind of hard copy format where people will be able to access it in 10 or 15 years from now? A: There's no equivalent today to these old atlases. The last one we made was 1984. There's no one to sell it to. People use street atlases now for driving. Q: What about official township records or records from some other governmental level? Will they have their own data on a computer to print it out? I've worked for the government doing engineering work and we've had problems where some of the drawings we generated in the early 1980s were stored in computer systems that were not PC-based. We left them to go to a PC-based system and now we don't have the ability to go back and read those old drawings. In some cases we still have hard copy, but sometimes, it's like, “Where is version 3?” A: Gone. I have tried to preserve the atlases of the area around here. I have most of them scanned in, but there's a few that are not. Some are on my Internet site but they cannot be printed. I don't want users to be able to print them because I don't want to compete with what I have for sale here. They're for information purposes only. Q: Do you have duplicates of the originals in case of fire? A: Yes, I have a full set at home. Andy Amsterdam graduated from Temple University in 1961 and has been connected with Franklin Maps ever since. This talk was presented at an April 17, 2005 Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society open house meeting at Franklin Maps, 333 S. Henderson Road, King of Prussia. It was transcribed by Bonnie Haughey.

|

||||||||||||||||