|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: July 1939 Volume 2 Number 3, Pages 59–74 New light on the encampment of the Continental Army at Valley Forge: Part V. The American outposts on the west side of the Schuylkill It is regrettable that so much traditional lore has been lost beyond recovery and that so little documentary evidence is available of the partisan warfare over the debatable zone of the trans-Schuylkill region during the British occupation of Philadelphia. Single and squad combats, deeds of daring-do and hair-breadth escapes were all enacted without a single historian to record or a bard to sing of the bravery, romance, or hardihood of the participants. The British were not well informed of the exact number and location of the Americans on outpost duty, but they never gave up the hope of establishing a strong post of their own west of the river, for, as early as December 22, 1777, an officer noted that the pontoon bridge having been laid, a considerable body was appointed to the defense of the lines, while the army marched across the river and hutted to an extent of three miles from Darby to Gray's Ferry. This movement, however, was only temporary, but as late as April 2, 1778, the chief engineer with a cavalry party reconnoitered the ground west of the river for a post, which they were unable to maintain. (Cf. Journal of Captain John Montresor). The enemy found a vast difference between a war conducted by regulars in accordance with the rules of military science and a series of guerilla skirmishes where all the advantages were with those fighting for their homes, especially in a wooded section broken by a series of hills, streams, and ravines. There was much skirmishing over the old Liberty lands (Blockley and Kingsessing Townships) where the British obtained firewood. The usual method of the patriots was to strike a sudden blow as soon as a small party appeared, and then flee before reinforcements could be rushed over the ferry or bridge, or at times to lure a party into ambush. Always, small, active patrols hovered before the van and upon the flanks of a superior force and cut off all stragglers. The time was indeed pregnant with deeds of heroism and the requisite endurance, nearly equal to but never beyond the best efforts of the hardy race of Americans. As early as October 1, 1777, the news of the day was that Smallwood's and Potter's militia had taken near Chester a large drove of cattle collected for Howe's army. On the fifteenth, Washington permanently detached the Tyrone-born Brigadier General Potter and his Pennsylvania brigade of militia from Armstrong's division and stationed them west of the Schuylkill to prevent the enemy from obtaining supplies in that well cultivated district. Potter was from Cumberland county as then constituted, and had, during the French and Indian war, served as an ensign in the battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Armstrong. He was wounded in the latter's daring expedition against a large war party at Kittanning under Captain Jacobs and his gigantic son, whom they killed with most of their murdering crew. The General is described as a stout, broad-shouldered, plucky, active man, five feet nine inches in height, of dark complexion, an excellent representative of the Scotch-Irish race, and his judgment and energy overcame his lack of education. He was ordered to collect provisions and clothing, especially shoes, stockings, and blankets, and to remove and secrete all running stones from the mills in the neighborhood of Chester and Wilmington, the former occupied by the British fleet and the latter by a detachment of Hessians under Colonel Lee. All millstones were to be marked so that they could be replaced later. The object, of course, was to prevent the enemy from grinding the confiscated grain at the mills on the Cobb's, Darby, Chester, Ridley, Naaman's and Brandywine Creeks. It is related that on one occasion a squad of British soldiers, observing a small party of Americans take refuge in the Robinson house on Naaman's crook, followed them into the hall and set guards at the front and rear stairs as the Americans retired to the second floor. The rear stairs being boxed or closed in, the besieged party removed their shoes, slipped down the stairs, opened a secret panel in the wall that led to tho kitchen, and escaped to their horses. This panel may still be seen. Potter's was a roving commission and Washington commended his activities and vigilance. He was reported in Newtown Township on October 14 with 1,600 men. (Cf. Diary of Robert Morton, Penna. Mag. Hist, and Biog. 1877, p. 18). According to tradition, the Lewis homestead on the Goshen Road a short distance west of Newtown Street, or Centre Square, served as his and Major John Clark's quarters for a time, and Garrett's house on the eighth of November. Since he needed mounted patrols, Colonels Cheyney of Thornbury and Gronow of Tredyffrin were ordered to form three or four troops of light horsemen without the loss of time. It was reported by an enemy spy that Potter had retired on October 14 as far as Foxhall and that of the 1,240 men with which he had been detached, he had hardly one-half when he arrived, the rest had disbanded. Hence an entire brigade consisting of five battalions of Pennsylvanians had been sent to Foxhall to reinforce him. (Cf. Baurmoister's letters, Penna. Mag. Hist, and Biog., 1936). Evidently the British were not sure their information was correct, for, on the twentieth, 100 ammunition wagons and a train of heavy artillery of eighteen pieces were brought to Chester for Colonel von Loo's corps, who had abandoned Wilmington. The escort under Brigadier General Mathews was composed of the English Guards, a battalion of tho 71st and 10th regiments. Some troops of Pattison's corps lost their way in tho woods and fired upon this escort. At the time of tho battle of Germantown, Jacob Latch, of Rose Hill, Lower Morion, a scout enlisted under Captain Young and Colonel Paschall, volunteered to cut the west end cable of the Middle ferry (Market Street) and accomplished the feat while under fire. On October 24, the Hessians constructed a bridge of boats over the Schuylkill at this point and threw up defensive works to cover the Chester Road. On the twenty-eighth, Major Cuylor, Aide-de-Camp to Howe was sent with dispatches for England to the mouth of Darby Creek, in order to board the packet. Tho 71st regiment escorted him, and on the thirtieth it was reported that the Americans had set fire to several of the boats that formed the bridge to the Middle ferry. The diary of Robert Morton tells of the frequent raids by American troopers on the British boat at the Middle ferry which was operated by a pully rope. They generally succeeded in making prisoners of the guard, cutting the cable, setting the boat afire and adrift, much to the annoyance of the enemy, and would then retreat out on the Lancaster Road, and Montresor notes that on the night of the thirtieth "the Rebels set fire to several of our boats that formed our Bridge at Middle Ferry and were carried away to the opposite shore. Thirty-first, repossessed the tote do pont at the Middle ferry without opposition. Knocked off one of the rebels thighs with a cannon shot." On November 3, Major John Clark, Jr., chief of the spy service, had reported to Washington that the enomy were employed in building three bridges of rafts of logs and boats with draws in two places to allow boats to pass. These floating bridges permitted wagons loaded with firewood to be driven over them. It is known that Colonel Clark accompanied Potter part of the time while he was chief of the secret service and that his spies, as opportunity permitted, dressed themselves as farmers, entered the City with loads of horse meat butchered from the war steeds shot under the British dragoon or Hessian yager, which they sold for prime beef for British gold, while making observations. On the eighth, the enemy lighthorsemen attacked two squadrons of American horse and with some loss captured the Major and a French officer. On the ninth, a sergeant, six light dragoons and several grenadiers of the Guard were captured by the American cavalry. On the tenth, the enemy bombarded with heavy guns Fort Mifflin from the ships of the fleet and from Providence Island, and by the fourteenth forced its destruction and abandonment. The unconfined Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers of that period formed backwaters of bewildering extent, little realized today, and made the relief of Fort Mifflin impossible by land. Potter, whose force was variously estimated at from 600 to 1,600 men, seemed to have become something of a bugaboo to the Hessians, for on November 14, Major Baurmeister reported that their late opponent had retired as far as the White Horse and Yellow Springs, which was untrue. On the evening of the eighteenth, Cornwallis crossed the Middle ferry with 2,000 men, on his way to Chester, ostensibly to convoy goods from that place to Philadelphia. He drove in the American picket of thirty-three men on the Darby Road, who sought shelter in the Blue Bell Tavern on Cobb's Creek and fired upon the advance, killing two or three of the enemy, including the sergeant major. The enraged grenadiers stormed the inn, raised the cry of no quarter to the rebels, bayoneted five Americans and would have massacred the whole party but for the intervention of their officer. Cornwallis crossed the Delaware, united his force with the 3,000 men under Sir Thomas Wilson from New York and attacked Fort Mercer at Red Bank. As soon as Washington was apprised of this movement he detached Huntington's brigade to join General Varnum at that place. General Greene's division was also ordered to repair to the same point and an express was sent to General Glover, who was on his way through the Jerseys with his brigade, to file off to the left toward Red Bank, with the addition of such militia as could be collected, but before these troops could effect a juncture the enemy appeared in force and the works had to "be abandoned." Cornwallis had accomplished that which Donop had so signally failed to do. The impartial student of history will readily see the impossibility of defending successfully the river obstructions without the assistance of a large part of the army, yet had Washington the prompt cooperation of Gates, it might have been accomplished. As it was, the American army was not strong enough to defend the Delaware forts without leaving the upper country at the mercy of the enemy. It is well that Washington held to the maxim of prudence, not to attempt too much lost he accomplish too little. He was tenacious in his resolution to cover his line of communication between the South and West Point and neither Howe nor Clinton ever succeeded in breaking it.

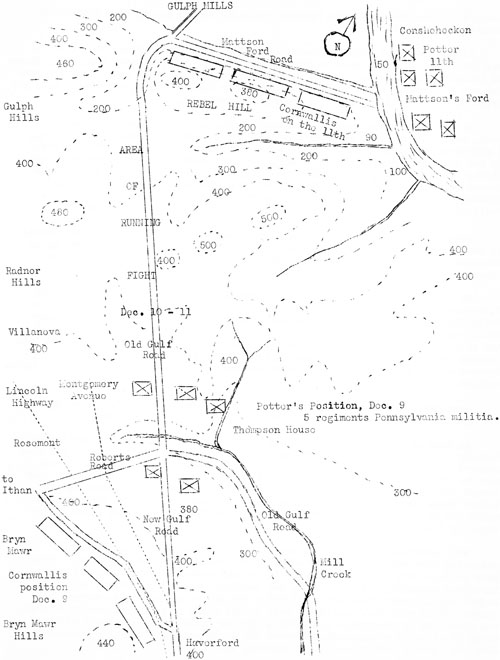

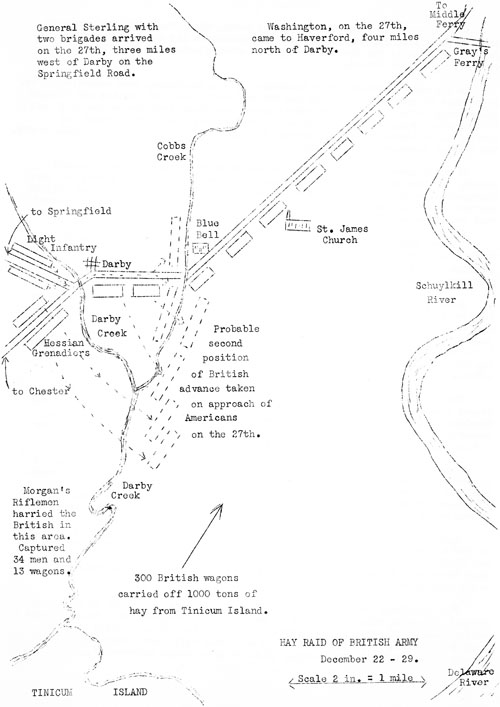

About the beginning of December all detachments, including that of Potter's, were called in, as information had reached headquarters that Howe was about to move upon the main camp at White Marsh. On the seventh, Colonel Webb's Second Connecticut regiment, supported by Potter's brigade, moved out to harass the approaching enemy, but, after a short skirmish in which many were killed or wounded, the militia were obliged to fall back. It was there that General Reed, in his attempt to rally them, had a narrow escape. His horse was shot through the head and came down, the enemy's flankers ran up to bayonet him, when Captain McLane rescued and conveyed him from the field. Immediately after the British retreated from Chestnut Ridge, Potter with five regiments returned to their old stamping grounds, when Cornwallis on the ninth of December, again crossed over the Middle ferry in a general forage beyond Darby. His van was fired upon by the alert American picket and by another patrol of 100 men from the Black Horse Tavern on the Old Lancaster Road. It was like a mouse confronting a lion. Cornwallis had with him 3,500 infantrymen and almost all of tho dragoons and yagers, and plundered both Whigs and Tories indiscriminately of their cattle and sheep, upward of 3,000 in number. This force included the light infantry, guards, 23d, 28th, 49th, 27th, and 33d regiments, chasseurs, Lengorke's battalion, 16th and 17th light dragoons, according to Major Andre, who acknowledged the great depredations committed on the march by the soldiers. It was feared for a time that they contemplated a raid as far as Lancaster; the papers and records of the Executive Council were removed by wagon from that town to York. Cornwallis spent the first night at tho Humphrey house, Bryn Mawr, and dispatched strong detachments as far up the Old Lancaster Road as the Sorrel Horse Tavern. Potter's men encamped on the estate of the Secretary to the Continental Congress, the Ulster-born Presbyterian, Charles Thomson (The "Harriton House," Old Gulf and Roberts Roads, now the residence of Mrs. Ralph Colton), and here the two forces, a short distance apart, confronted each other on what the early Welsh settlers called Bryn Mawr (Great Hill). Potter stationed two regiments in advance, who attacked the enemy with vigor; and on the next rise placed the three remaining regiments; with orders to the first, when hard pressed, to retreat and reform behind the second line. In this way his militiamen fought, retreated, and reformed upon hill after hill for four miles until Mattson's Ford was reached. He reported that his people behaved well, especially the regiments commanded by Colonels Chambers, Murray, and Lacey. Though pitted against the veterans of Europe, he had employed Washington's tactics with success and he declared that if General Sullivan's two divisions had supported him instead of falling back across the river, there would have been more cause for Washington's congratulation. It was a coincidence that the van of the patriot army arrived at Mattson's Ford from White Marsh on their way to Valley Forge on the eleventh as Potter's militia crossed and Cornwallis arrived to occupy Rebel Hill. The possession of that eminence absolutely commanded the ford, so Potter hastily withdrew and partly demolished the bridge of wagons. A writer states that they made a headlong flight in which they threw away their guns, but Washington, in a note to tho President of Congress, stated: "They (the British) were met in their advance by General Potter, with a part of the Pennsylvania militia, who behaved with bravery and gave them every possible opposition till he was obliged to retreat from their superior numbers." Cornwallis returned whence he came, recrossing the Middle Ferry where General Grey had been posted to secure the retreat of the wagons. In the records of the Radnor Men's Monthly Meeting there is an item of 284 pounds, 10 shillings, and 2 pence, the value of which was taken 12.12.1777, by the detachment under Cornwallis, and of only 5 pounds and 17 shillings by the army under Washington, and from Isaac Bartram and Abraham Loddon, same day by the British 96 pounds, 20 shillings, 9 pence, and by the Americans 3 pounds, 0 shillings, 8 pence, showing that the enemy robbed to excess while the Americans took little. The command of Cornwallis, upon one occasion, visited the house of Joseph Burn, Chester Road, Marple Township, and actually stripped it bare, as well as took the owner prisoner. An itemized list of his loss is on file, and includes all food stuff, household utensils, tools, arms, liquors, books, bedding, and personal apparel, not excluding stays, shifts, petticoats, aprons, caps, gowns, and bonnets of his wife, and of no possible use to the looters. Although the British army was largely officered by gentlemen, the opposition to the war in America by a large class of Englishmen rendered service in the ranks unpopular and led to the enlistment of an unusual proportion of the riff-raff of the nation, therefore, wherever the British army had been stationed in the Colonies, their more than occasional acts of rapacity, arrogancy, and cruelty had alienated many of the inhabitants. The prejudice in this vicinity had endured to the third or fourth generation. The writer as a small boy had often heard the expressions: "A dog before an Englishman," "'Damn' an Englishman a day old," etc., now happily forgotten by the commonalty. About this time it is related by the enemy that a patrol of mounted yagers fell into an ambuscade while attempting to engage an American picket. Two yagers were wounded and another fatally shot as was his horse near where many Hessians were cutting firewood at the Middle Ferry. Scarcely had the Continentals become established at Valley Forge, when on the twenty-second word arrived that the enemy was about to make another raid in force toward Chester. Washington ordered Generals Varnum and Huntington to hold their brigades in readiness to march against the enemy. Baurmeister writes: "A scanty supply of forage and fresh food compelled General Howe to cross the Schuylkill with a larger part of the army and encamp on the left of the main road this side of Derby in a line four and a half miles long. The Hessian grenadiers were ordered to encamp beyond Darby. To make their left flank secure against a possible attack from Springfield the English light infantry took position on the Springfield Road. A scouting party of one officer and twenty horse of the 17th dragoons followed the Darby Road toward Wilmington and foil into ambush, they lost thirteen horses and eleven men were taken prisoner. On the twenty-sixth and twenty-seventh General Washington sent two brigades under General Sterling from Valley Forge to Springfield while he himself advanced as far as Harford (Haverford). On the twenty-ninth Washington retired to camp and Howe to Philadelphia." According to Major Andre's sketch (Cf. Andre's Journal) Howe's position the twenty-second was as follows: The 44th regiment, flanked by tho yagers, guarded the approach to Gray's ferry; then the guards, 29th, 28th, 5th, 27th, Anspath battalion, 7th, 63d, and 26th regiments were encamped along the Darby (now Woodland Avenue) Road between the ferry and the St. James (Old Swede) Kingsessing P. E. meetinghouse, in the rear of which was the general headquarters.

Hay Raid of British Army December 22 - 29 Between the church and the village of Darby, along the same road, were the 33d, 42d, and 17th regiments. The British grenadiers lay north of Darby, and the Hessian grenadiers, the 1st and 2d light infantry guarded the roads beyond the village, as already stated. On the twenty-seventh, when threatened by the Americans, Howe consolidated his left flank by drawing in the 17th and 42d regiments, also the British and Hessian grenadiers, to the east side of Cobb's creek; the light infantry to the west bank of the same stream, on either side of the Darby Road, and neither sought nor desired an engagement with Washington. In their retreat by way of the Middle Ferry, the British destroyed Gray's Ferry. It would appear that this force was accompanied by Quartermaster General Erskine and they had 300 wagons. Morgan's riflemen harried their flanks and took thirty-four prisoners, and according to Christopher Marshall's diary, the militia captured thirteen loaded provision wagons. Hay on Tinicum Island was the enemy's real objective and they removed 1,000 tons. General Knyphausen, with a depleted garrison had remained in Philadelphia. Colonel Bull with a brigade of Pennsylvania militia, was sent in a counter demonstration against the enemy's line east of the river. He planted his battery and discharged cannon balls as far as Christ Church and caused a general alarm. Washington's report from headquarters was: "The enemy returned into Philadelphia on Sunday last, having made a considerable hay forage, which appears to have been their only intention. As they kept themselves in close order, and in just such a position that no attack could be made upon them to advantage, I could do no more than extend light parties along their front and keep them from plundering the inhabitants and carrying off cattle and horses, which had the desired effect." The vigilant Potter, Morgan, and Smallwood doubtless commanded the light troops thus employed. The latter had been ordered, on December 19, with the two Maryland brigades of Sullivan's division to occupy Wilmington (which had been evacuated by the Hessian detachment), to put that place in the best posture for defense and to cover Darby and Chester. Soon after Cornwallis' raid, Wayne despoiled this narrow debatable zone of everything he deemed worth carrying away, in a sweep across the Delaware through New Jersey, completely encircling Philadelphia and the British army. The latter to conceal their chagrin, dubbed him "Drover Wayne," but he brought home the beef on the hoof, which otherwise would eventually have fallen prey to the enemy. Again Major Baurmeister writes: "The British army, active as it is, has got no further than Philadelphia, is master of only parts of the banks of the Delaware and Schuylkill and has no foothold whatsoever in Jersey from where, as well as from Germantown in front and Wilmington, Derby, and Chester in the rear, it is being watched and constantly harassed by the enemy's outposts. "The Americans are bold, unyielding, and fearless. They have an abundance of that something which urges them on and cannot be stopped. Then their indomitable ideas of liberty, the mainsprings of which are held and guided by every hand in Congress. With little show the Americans will exert themselves to the utmost to gain complete freedom and they are by no means conquered."

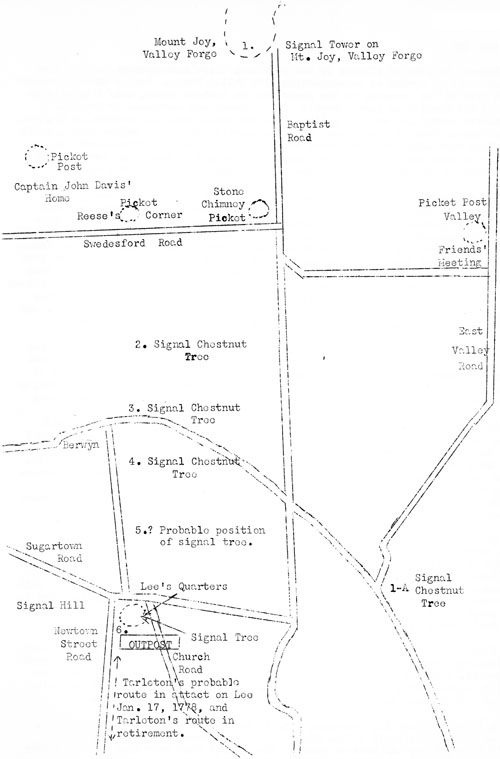

Beyond the line of pickets of the main camp there were outposts with a more or less complete system of communication with Valley Forge. One of these connected Signal Hill at the crossing of the Sugartown and Newtown Roads, half a mile or so south of old Cockletown (now Berwyn). This outpost was commanded by Captain "Lighthorse Harry" Lee who had a line of signal trees from his quarters to Mt. Joy, Valley Forge. Some of these trees had been pointed out to the writer when a small boy. They were large chestnut trees with their tops lopped off to permit the erection of rude scaffolds for the observers to signal to camp, the detection of an approach of the enemy or of a farmer hauling supplies to the City Market. An observatory of this nature stood in the middle of Cassatt Avenue, half way between the Conestoga Road and the Turnpike, Berwyn, until removed to grade that avenue. Another stood in the clearing of tho Burn farm, nearly on the rear line of the present Bair estate. Its immense trunk is still visible after repeated efforts to burn it. A third stood on a private cartroad which may easily be traced - along the Burn and Reese woodlots and on down into the valley to the Griffith John plantation. This was an unusually lofty Chestnut with a girth of twenty-six feet near its base and stood on the west side of the private right of way on the northern slope of the South Valley hills overlooking Valley Forge. Its fallen trunk lies rotting on the ground. This tree apparently formed a link visible between Mt. Joy and the tree on the Burn farm, and the latter to the one on Cassatt Avenue. There was probably another tree along the Waterloo Road bordering the Coates estate, and, of course, there was tho one on tho crest of Signal Hill. The exact method of communication employed is unknown but it is thought that the report of gunfire brought one after the other vidette to his observation post where messages were conveyed by means of flags, mirrors, or torches according to circumstances. On the highest point along the Newtown Street Road, in front of the David Thomas house, now the Aronimink Golf Club grounds, there was a sentinel or signal tree, an oak, now gone. This tree top commanded a view quite to the City on a clear day, and, it possibly linked with two others on the north with Signal Hill. By the aid of those observation posts the vigilance of Lee and his troopers intercepted a large part of the supplies intended for the City market. The drivers usually received a stated number of lashes upon their bare backs and their produce was confiscated. The late William Wayne, Jr., had a letter from General Wayne to his wife which throws some light upon the prevailing habit of all classes to evade the embargo on provisions. Probably through Captain Lee, General Wayne had received unofficial word that his thrifty wife had been detected in her attempt to run the blockade. In his note to her the General wrote in substance: Though British gold seems more desirable than Continental notes, the American Army is striving hard to keep supplies from the enemy and your actions, if repeated, may compromise my honor as a Continental officer. Since the British were in great need of country produce, and as Lee had been particularly active in stopping the supply from this quarter, a scheme was formed in January, 1778, to surprise and capture him in his quarters at tho stone house owned by James Scott, now the estate of Dr. Stout. Tho same buildings were also used as a storehouse until the goods could be transported to the camp. A force of about 200 dragoons, led, it is said, by the notorious Tarleton, made an extensive circuit on the night of the seventeenth, probably by way of Gray's Ferry, Darby and Newtown roads. They seized four patrolmen without giving an alarm and arrived at dawn in a most daring raid. According to tradition in the Tryon Lewis family, one of the women in the farmhouse along the Darby Creek Road observed the long line of horsemen as they passed, but being a Quakeress and in fear of bloodshed, she did not awaken the men. The farmhouse in which she lived was used as a billet by some of Morgan's men probably attached to the commissary. Lee's force, at his quarters, was insignificant, five men and four officers including Major Jameson who commanded two troops on the eastern side of the river and here present on a visit. One of the men saw the British coming and Lee had a moment's warning. The quartermaster sergeant attempted to save some of his stores, was severely sabred, and made prisoner. The British dragoons immediately surrounded the house, sounded a parley, demanded instant surrender or the house and its defenders would be burnt. Lee's reply was "Who but a fool ever threatened to burn a stone house?" Meanwhile the patriotic owner, who, at the first alarm, had succeeded in evading the enemy, carried word to a detachment quartered in the Great Valley and Colonel Stevens was dispatched with a battalion of infantry to the rescue. (Cf. Signal Hill, by Julius P. Sachse.) The doors were immediately barred and though there were not enough men to guard all the windows, Lee placed his men so effectually that he repulsed an assault. One of the bravest was Ferdinand O'Neil and but for the flashing of his carbine, Tarleton would have fallen in his attempt to enter a window. However, he glanced up with the utmost coolness and exclaimed, "You have missed, my lad, for this time." There was little protection in the yard, so the dragoons fell back, though their shots spattered the wall and woodwork of the house. Obviously the surprise had failed, so after half an hour's indecision they turned toward the stable to drive out Lee's horses, but drawn to the west windows, Leo's men delivered a volley while the Captain shouted, "Fire away, boys, here comes our infantry, we'll have them all," and Lieutenant Lindsay, with the blood dripping from his wounded hand, rushed upstairs, opened a north window and eagerly beckoned, as if reinforcements were close at hand. The ruse was successful, the enemy spurred quickly in tho direction whence they came, having accomplished nothing commensurate with the boldness of the enterprise. They vented their rage upon unprotected farmhouses in their retreat by way of Newtown and Darby Records of various claims are on file, among others that of David Thomas (Wyola). "To clothing and other articles taken out of my house by light horsemen on their return from an attack upon Captain Lee in Easttown - 5 pounds, 3 shillings, 2 pence." The British loss was a sergeant and three privates killed, and three privates wounded. The dead were buried in the old Welsh graveyard across the road and the spoils of war, the arms and cloaks of the wounded were gathered. Lee had saved his horses. So far as we know this futile attempt was the only armed attack so far west of the enemy's base. Later Lee met Tarleton in the Carolinas where the odds were not so great. On the twenty-first, Washington, in his general orders, gave thanks to Lee for his gallant conduct, and later, recommended him and his officers to Congress as having uniformly distinguished themselves by conduct of exemplary zeal, prudence, and bravery. Congress, to reward their merit, resolved that Captain Lee be promoted to the rank of Major and empowered to augment his corps by two troops of horse. Lieutenant Lindsay was promoted to the rank of Captain and to command one of the troops and Cornet Fayton became Captain Lieutenant. It is said that Captain Lindsay never recovered the use of his right hand and was obliged to resign, but Sergeant Winston, Privates O'Neil and Gardner eventually received commissions in Lee's Legion. Henry Lee was the son of Washington's "Lowland beauty" and he regarded the youth with favor. At this time Lee was only twenty-one years of age and fresh from Princeton College, yet he had already distinguished himself with his small troop of Bland's regiment when he cut off a detachment of the British some days before the battle of Brandywine and brought in twenty-four prisoners. Blond, florid, and freckled, with alert blue eyes, a slight active figure and round chin, his appearance was even more youthful than his years. He is said to have worn his hair powdered and tied in a queue. His uniform consisted of a bright green jacket, high frilled stock, tight lamb-skin breeches, polished boots, and a leathern cap surmounted by a resplendent white horsehair plume. He later became a Major General and the father of the great Confederate General Robert E. Lee. (Cf. Signal Hill, By Julius F. Sachse). Rebel Hill commanded a narrow and important pass known as the Gulf and also Mattson's Ford, the lowest on the Schuylkill. Here a regiment of militia was early stationed. With little discipline, they were in the habit of exciting false alarms, in consequence of which the troops of the main camp at Valley Forge were obliged to turn out constantly. General McDougall became exceedingly annoyed and recommended that Lieutenant Colonel Aaron Burr be given the command of the post. Colonel Burr at once instigated a rigid system of police, visited the sentinels every night and at all hours of the night, while during the day he kept the men under constant drill. In consequence, he was advised that the men contemplated mutiny. He then ordered the cartridges withdrawn from all the muskets, provided himself with a well-sharpened sword, and paraded the detachment on a cold, bright moonlight night. When formed, he marched along the line until he came opposite the most daring ringleader of the malcontents who advanced a step, lowered his musket and shouted, "Now is your time, my boys." Burr smote the arm of the mutineer above the elbow, nearly severing it from his body, ordered him to take and keep his place in line. In a few minutes he dismissed parade. The next day the man's arm was amputated and no more heard of mutiny nor were there any more false alarms, though Burr narrowly escaped court martial. (Cf. Memoirs of Aaron Burr, by Matthew L. Davis). Colonel Daniel Morgan, next to Anthony Wayne, was probably the greatest natural-born soldier of the Revolution. He was born somewhere along the banks of the Delaware, but whether in New Jersey or Pennsylvania is unknown. His regiment was nominally included in Woodford's brigade but often acted independently. An old chart of the encampment places his command on the extreme left of the outer line, while Woodford's position was on the extreme right. It is probable that Morgan's riflemen manned John Moore's fort, since his quarters, according to tradition, was nearby. But his stay in the main camp must have been brief for he was soon assigned duty in the advanced outposts. Potter on December 28 in a letter from Radnor stated that a detachment of Continentals with Morgan's riflemen were sent from Valley Forge to operate with the Militia under his command and that they had kept close to the enemy's lines. On the twenty-third, but one American had been killed and two wounded, while upward of twenty British had been captured and a number of deserters had made their way to his lines.

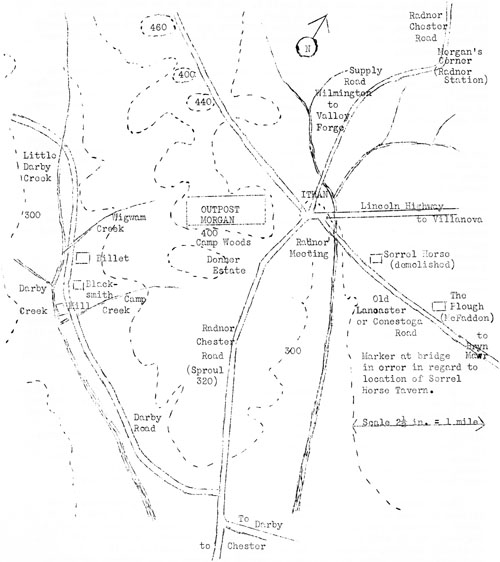

Morgan's sphere of action and of observation was between the Darby Creek which flows into the Delaware at Tinicum, and the Gulph hills on the Schuylkill. The Radnor Friends' meeting house was appointed as the rendezvous in the event of a repulse, and was also used as a hospital. Camp Woods on an easily defensible hill at an elevation of 400 feet, a short distance south of Ithan, harbored some 200 of his troops, and the intermediate territory was covered by a numerous patrol of horse and foot, while the main detachment moved from place to place as circumstances demanded. Morgan was charged to watch every movement of the enemy and he had scarcely been on the ground a week when a force of 1,000 enemy foragers appeared near Darby. Morgan's frontier riflemen were joined by Lee's and Pulaski's Cavalry and a number of small detachments from the main camp, for Morgan had the authority to draw upon the Army at any time for any number. Lieutenant Colonel Butler fell in with a troop of dragoons and captured eleven men and twelve horses beside recovering a prisoner from Lee's troop, captured only an hour or two before. The letter recounting this exploit is dated December 23, and after this date a party of the enemy was fortunate indeed to pass unchallenged through the line occupied by Morgan's command. The outposts had also to guard the Radnor-Chester Road and its continuation along their front, over which the wagons laden with supplies from Wilmington and below were routed for Valley Forge. The course of this road may easily be traced part of the way west of and parallel with the Sproul Road, through Marple and Radnor Townships. It continues as of old from the Ithan store through Morgan's Corner (Radnor station) and over the hills to the King of Prussia Tavern, where it connects with the Gulph Road. One can readily see its value also as a military road over which the light parties of troops could move quickly to any threatened point. Woodman states that Colonel Morgan's quarters were at Mordecai Morgan's home at Morgan's Corner, now Radnor, but his was a shifting command, and sometime curing the winter he returned to his home in Virginia for a few weeks' rest to recover his health. Lieutenant Colonel Butler was promoted to the command of a Pennsylvania regiment so the command of the backwoodsmen devolved upon Major Posey until Morgan's return in the spring. No adequate biography of Morgan has been published. He was born in 1756 and as a young man worked his way through Pennsylvania to the Virginia frontier. Here he was a teamster in the quartermaster's department during Braddock's campaign against the French and Indians. During this war he exchanged some words with a British officer who struck him with a sword and Morgan promptly knocked the officer down. For this he was sentenced to receive one hundred lashes and actually was given ninety-nine, which cut the skin and flesh of his back into ribbons and only his strong constitution saved his life. It is said that the officer later became conscience-stricken and publicly begged Morgan's pardon and was forgiven. This incident left a deep and lasting impression on Morgan, however. When his own men were convicted of misconduct they were never whipped in public, but led to a secluded place, admonished for their misdeeds, and sometimes received a few sound whacks with a stick if the case seemed to warrant it. Public whipping, he rightly claimed, destroyed a man's morale. On one occasion he is said to have shed tears when, during his absence, a man of his command was whipped before the regiment. He said that he knew the victim's family who were of the best and he mourned the lost character of the boy. (Cf. Life of General Daniel Morgan). Woodman states that Morgan, while he confiscated the produce and goods of a farmer caught bound for the City market, never inflicted the extreme penalty of lashing commonly practiced at the main camp. His letters are few and command a good price, selling recently for $37.00 each. His early letters written while a wagoner in Braddock's army are quite illiterate with phonetic spelling but they improved later. Something may be learned of the partisan warfare from the enemy's letters, "March 24, 1778, On the seventeenth a detachment of light infantry surprised a troop of rebels on the Westfield Road on the other side of the Schuylkill, killing four and taking eighteen prisoners. At Gulph ferry mill is a strong enemy outpost. On the night of the nineteenth and twentieth this post sent out a party of sixty men who crept up opposite the 10th redoubt where they collected some cattle and set fires. Captain von Munchansen, with forty mounted yagers under Lieutenant Metz, was fortunate as to catch up with this party the following morning just as they reached Black Horse tavern (Lancaster Road or 54th and City Line). He captured an officer and ten men and killed and wounded several more." "April 16. The entire Hessian yagers corps crossed the Schuylkill and advanced beyond Darby, Captain von Wreeden covered the right during the march in the dark. His pickets, marching directly in front, encountered an infantry patrol of one officer and eighteen men. Several rifle shots betrayed the presence of the yagers, one of whom was wounded slightly. One rebel was captured, from whom we could learn almost nothing." (Cf. Baurmeister Letters). The enemy listed the American outposts west of the Schuylkill as at "Darby, Ready Tavern, and the Gulph, with an observation post at Springfield." There was another at "Camp Woods," now the estate of William H. Donner of Radnor Township, on the summit of a steep hill which required breastworks only on the north. Nearby there were formerly two small buildings. Some little distance in the rear along Darby Creek where the Wigwam and Camp runs enter, there is a stone farmhouse where, until recently, the same iron pots hung in the kitchen fireplace from which the soldiers were said to have boiled their mush of corn meal. Nearby are the sites of the blacksmith shop and the grist mill. From this not uncomfortable rendezvous the riflemen cheerfully sallied forth daily, eager for a brush with the enemy. It is possible that from here or from Morgan's Corner, a line of signal trees extended all the way to Valley Forge, but only one, a chestnut, is known. This tree stood at the northwest corner of the Eagle and Conestoga Roads, just west of the Spread Eagle Tavern. By early spring the British army was obliged to import from Rhode Island, forage for their horses, and of the seven transports loaded with hay, two were boarded and burned on March 8 by nine armed boats and galleys on the Delaware between Reedy Island and the mouth of the Christiana Creek. At the same time the British schooner "Alert" was captured by Commodore Barry. It was laden with tho trappings and cloth, blue, buff, and scarlet, enough to clothe all the officers of the British army. This was a gift very much appreciated by the Americans at Valley Forge. There was also a package of letters and drafts from Counsellor of War Lorentz to Paymaster Schmidt, which, on the tenth were returned under a flag of truce, with a very courteous note from Washington to General von Knyphausen. Many dispatches passed from Headquarters to the outposts signed by Tench Tilghman or John Laurens, two of General Washington's Aides-de-camp. On May 23, Morgan was instructed to keep strict watch near the enemy's bridge over the Schuylkill and other places for an eruption in his way and to communicate with Colonel Smith at the Gulph and also with Colonel Schaik. On the seventeenth, Morgan detached fifty men under Captain Parr to join Lafayette at Barren Hill where the Marquis had taken post. At the same time Morgan marched his main force from Radnor to some distance down the eastern side of the Schuylkill and then up to Mattson's Ford to protect Lafayette's retreat, after which he returned to Radnor Township. On the twenty-ninth, Morgan was instructed to warn Smallwood if the enemy was prepared to move, to keep two of his best horses ready mounted and dispatch them to Smallwood, one a little while after the other for fear of an accident to the first horse. He was also ordered at the same time, as soon as he received certain intelligence of the evacuation of the City, to return with the whole force of his command to camp and not suffer a single soldier to enter Philadelphia. It is no disparagement to the general historian that he had failed to mention the remarkable system of coordinated outposts employed by Washington but the local historian should not be ignorant of these facts. The tale of how Potter with his local militia boys and, later, of Morgan with his hardy, scrappy, and sharpshooting Pennsylvania and Virginia bordermen defended the trans-Schuylkill region, might be continued further. It is evident that Morgan's later glorious victory at the Cowpens was the fruition of his experience at Saratoga and at Valley Forge. Editor's Note: The following list of corrections to the text of this multi-part extended article was included at the end of this section in the original publication. The line numbers refer to the original printed layout and may differ from this digital version. Errata

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||