|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 18 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: January 1980 Volume 18 Number 1, Pages 3–14 Diamond Rock School Situated in the North Valley Hills of Tredyffrin Township of Chester County, Pennsylvania, the octagonal school house, "Diamond Rock", bears mute testimony to the desire of the early nineteenth century residents of the Great Valley to see that their children had the advantages education would bring them. Here, on September 21, 1818, these foresighted citizens opened the first school of free education in the eastern part of Chester County, [Note 1] David Llewellyn, a Welshman, was one of the early settlers of the county. He owned a thousand acres of land, about three miles north of Paoli, As the country became settled, he sold five farms, retaining for himself the "Diamond Rock" tract of land of about 117 acres. It took its name from a piece of rough boulder on the farm, of extreme hardness, lined with beautiful crystalized quartz. The quartz is so hard it will cut glass; there is no other known quartz like it. On a sunny day, the early residents of Paoli could see the hill, sparkling like diamonds in the sunlight. William Perm was so impressed with the idea of precious metal being there that he withheld title to the land until an agreement was reached whereby 20 per cent of the output at the mouth of the shaft would be paid to Penn's heirs by Llewellyn. [Note 2] But there never was any precious metal. The daughter of David Llewellyn, Ann, used to say that "farm after farm was sold until only the home place was left, 'Diamond Rock', with the old log houses and stables, and as George Beaver wanted it, I just thought I would marry him and stay on, for I always liked it here". [Note 3] In 1817 George Beaver built a big stone house, where they lived for over sixty years. This house remained in the family when their only daughter, Ann E. Beaver, married George Wersler. George Beaver was interested in the education of the youth. He called a meeting of his neighbors, and together they planned a school building. He donated a plot of ground for school purposes for 999 years. In January 1818 construction began, and the school opened on September 21, 1818. [Note 4] They could not have chosen a more commanding spot, overlooking a scene of incomparable beauty. Here could be seen the beauties of the wondrous landscape so lavishly spread out in this picturesque valley of our forefathers. [Note 5] The cost of the school these early settlers so keenly desired was underwritten by forming a subscription list. Those who subscribed, under the date of January 12, 1818, formed the original agreement subscription list now posted on a wall of the restored building. Two of the subscribers to this agreement wrote in German script; their names cannot be deciphered. In fact, the founders of the school were largely of German and Welsh descent. The final cost of the school to the founders was two hundred sixty dollars and ninety-three cents. Those who were not able to subscribe money donated labor by hauling, carpentry, and masonry work. [Note 6] Why did the builders adopt an eight-sided design for their school? Actually, there were many octagonal school houses erected during the early and mid-nineteenth century. The builders in those days were practical people, and that which was the most functional gained their favor, A statement presented in an architectural journal of 1853 bears this out: "The nearer in form we can approach the circular, the better. The octagonal form serves better than the square and is preferable in every way," [Note 7] (Miss M. Ella Wersler, one of the last owners of Diamond Rock Farm and a former pupil at Diamond Rock School, often gave another explanation of why her grandfather, George Beaver, favored the octagonal shape. It combines a bit of history and a bit of legend: the story of John de Groat. It was that doughty Scotsman, according to the tale, who originated the eight-sided building, to keep peace among eight strapping and truculent sons. Back in the reign of James IV of Scotland, de Groat lived at the very tip of Caithness on land obtained by Royal Grant when he migrated from Holland. Annually, the clan gathered to celebrate its safe arrival in Scotland, and annually there was a row. Each son wished to sit at the head of the table. There finally came a meeting for which John de Groat had prepared in advance — by building an octagonal house, with eight doors, eight windows, and an octagonal table to stand in the middle. He escorted each son through a separate door, placed each at the end of the table, and so good humor reigned.) [Note 8] The octagonal design had its advantages. With eight corners, it conserved space. It also made for cheaper construction, better lighting, and more comfortable heating. All eight corners were closer to the stove in the center of the room than four corners would have been. Furthermore, a child sent to stand in a corner had eight to choose from, and he saw forty-five more degrees of the world than he would have seen from a four cornered room. The old one-story, one-room school house is a near-perfect octagon. It is a little more than twenty-six feet across at its widest point. Each of its eight twelve-inch thick walls is about ten feet long. The teacher sat at a high desk across the room from the one and only door on the west side. Her back was to the wall, but the hickory stick lay on the window sill close at hand. The children sat on benches arranged around the stove, but they turned their backs to it when they were reading or writing. This meant that their hands got cold, but they had plenty of light from the eight windows. [Note 9] Near the center of the room stood a table with low benches for the small children. These little ones would often cry with cold when the fire was built late on a cold winter morning, but most of the time they were nearly roasted by the cast-iron wood stove which stood in the middle of the room. They must have been pretty well smoked, too, for the wood donated by their parents was often green. [Note 10] The desks were crude and unpainted, blackened by use, and hacked by penknives. The walls had no pictures, and there was nothing to view but the weather-stained and crude, umbrella-like rafters. [Note 11] The pupils sat on hard, backless benches, so high that many feet swung above the floor. [Note 12] Mary Rossiter, a former pupil, "could recall just where she sat on a bench near the stove which occupied the center of the room. The stove pipe passed straight up in the middle toward the ceiling. The low benches around the stove were reserved for the small folk. She remembered afterward being promoted to the dignity of a desk". [Note 13] Drinking water for the school was carried in an old oaken bucket from "Sycamore Springs" on Yellow Springs Road. A visit to the school today will show many things used when the school was in operation. Many of these have been donated to the school by descendants of former pupils. The original school master's desk, quills, hickory sticks, the kettle and lunch pail racks, copy books, samplers, textbooks, teacher's glasses, slate pencils, little double slate pads, a school bell used by one of the teachers, these and others are all on display. Think of teaching sixty to seventy pupils, both boys and girls, in so small a room! The teachers were chosen by the trustees or directors. To attract teachers, advertisements sometimes appeared in the newspapers. The teachers were boarded at the homes of different pupils. Their salary was low — three cents per day per pupil. [Note 14] The curriculum consisted of reading, writing, mathematics (including surveying), grammar spelling, geography, and history. The degree of thoroughness varied with the teacher. The teacher also had to be an expert in manufacturing pens from goose quills. A large bundle of quills was usually found upon the desk, and in leisure moments were shaped into pens with the aid of a knife. [Note 15] Instructing pupils in the "three R!s" was the declared aim of education, but discipline was a prime part of pedagogy in those days. "A boy has a back; when you hit he understands" was a popular axiom. Many a lad knew that a thrashing in school brought another at home. In the first half of the 19th century, school was not graded. Each pupil represented a separate grade. He carried to classes such books as his family owned, and the teachers accomodated the lesson to the book. Unconsciously, teaching began to bow to psychology: instead of featuring punishment for misdemeanors, they rewarded good conduct by bright slips of paper attesting that the recipient had merited approbation by "diligence and application". [Note 16] Following are a few excerpts from an article written by W. W. Thomson about the teaching situation when his brother, Joseph Addison Thomson, taught at Diamond Rock. It appeared in the Daily Local News in 1918 and was entitled "In the Early Fifties": "During the period of my brother's teaching here, he conceived the then rather progressive idea of forming a class in what he termed 'Syntax', in which he intended to give the older pupils an opportunity to express their thoughts on subjects he chose to select for them. He went down into his trouser!s pockets for the necessary dime with which to purchaae the copy books for the use of the class. In each book he wrote the subject assigned the holder, and I recall that mine was 'Cider', how it is made and its uses. "I had about filled the bill of requirements to my satisfaction when three members of the township school board entered the school room and very forcibly expressed their dissatisfaction at what they were pleased to term "a new fangled idea" and ordered it to be set aside at once. We pupils heard the order given and we looked in wonder as to what would come of it. My brother respectfully listened to the gentlemen through and then made the following reply: "'Gentlemen, I recognize the fact that I am subordinate to your ruling and must comply with it or lose my position, but I wish to remark that inasmuch as all of you are comparatively young men, I take occasion to say here and now that you will live long enough to realize your mistake in your stand taken today.' "The spring session of the school extended well into warm weather. During Addison Thomson's term as teacher, it was his custom and pleasure to take the pupils to the 'Diamond Rocks' in the woods, west of the school, and there hold the afternoon session, a change which was highly enjoyed by all participants." [Note 17] The fame of a good teacher would lead ambitious young men to tramp several miles to attend school. We find them enrolled from Charles-town on the west, from Valley Forge on the east, and from all parts of the valley. They walked these long distances willingly, for the sake of an education. [Note 18] Mary Ann Clemens, a pupil at Diamond Rock, it was reported by her son, Lewis Pyle, ofter described her three mile walk to and from school morning and evening. Oftimes in the morning she had to run much of the way to avoid being late. [Note 19] Miss Annie M. Dunlap also told of the old horse, "Tobby, perfectly blind, upon which her mother, the former Ann Sloan, and other children rode to school. The animal made its way home when released at the school grounds". [Note 20] During the winter term, as many as sixty scholars attended Diamond Rock School. They were mostly young men and women, as the younger children were allowed to go only during the spring and fall. The pupils placed their kettles and dinner buckets on the open cupboards which flanked the door. The only provisions for their clothing were a few pegs. [Note 21] The larger boys exercised their muscles during the noon hour by sawing cordwood into stove lengths. The wood was donated by their parents and nearby farmers. Boys' hats were often found replacing broken window panes. [Note 22] Boys were a discipline problem then, too. W. W. Thomson also recalled, in his memoirs previously quoted, when John and Ephraim Brooke, from the village of Cedar Hollow, were pupils at the school: "John was a mischievous boy, and frequently his antics called into action the governing power of the teacher's rod. On one occasion John seriously interfered with the discipline of the school. My brother, Addison Thomson, proceeded to administer a flogging upon the offender. The boy was a supple fellow, and before the teacher was aware of it John was upon the shoulders of the teacher. The situation was unique. The teacher being unable to inflict the prescribed punishment, a compromise was effected between the teacher and pupil, before the latter descended from his perch." [Note 23] Not long before her death in 1933, Miss M. Ella Wersler, a former pupil at Diamond Rock, reminisced of her school life at Diamond Rock; "I was born November 5, 1850, Guy Fawkes Day, and began going to school the fall of 1856. My first teacher was Mr. Brown with beautiful hair. The pupils loved him but the directors discharged him. Next was Mr. Carpenter, greatly disliked; he it was who held me up before the crowded room as an example of plagiarism: I a timid eight year old who had never heard the dreadful word before. I had copied a pretty little child story for my first essay, and I can still feel the hot indignant thrill as I stamped my foot and vowed, 'After this I will do my own writing.' "Carpenter used leather spectacles to punish us for whispering. I wore them once. His career culminated in a free rail ride by the big boys, of whom in winter there would be eighteen or twenty, almost grown-up, and a more loyal, independent bunch would be hard to find. "The classes in spelling and geography would wind around three sides of the room — no honor to be head because you could not tell where the head was. With over sixty pupils and a hot stove in the center, it was a busy, bustling company. The north side desks were filled with girls up to young womanhood. Back of the teacher's desk was a long blackboard which supported a row of hickory switches, used to punish refractory pupils — mostly boys — but I have seen girls struck with a flat ruler on the palm of the hand. "I recall most clearly the delight in sports — great rings of Copenhagen and tap" hands on the front lawn... But oh! the games of ball — corner ball — played in the adjoining fields by the big fellows. The next grade would be wildly enthusiastic over 'Tickley I Over', which was sung out shrilly as a swift ball sailed over the roof to be caught by the opposing force on the opposite side of the building. 'Socky Up' was played on the south side — shutters closed, a boy standing near the wall alert, for in the road was the team with a hard ball, doing their best to hit him — he by swift jumps avoiding. "There was roll call in the morning, singing and Bible reading, and in the geography classes, the State Capitals and on what river was sung and indelibly impressed on our minds. "As no institution of learning can flourish without a nearby Emporium, so we had ours at the top of Diamond Rock Hill — Daddy Hill, who sold pencils, paper, gum drops, and stick candy. He was a great favorite — also the local shoemaker.

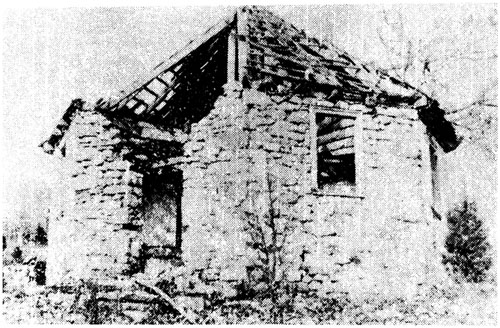

"So — down many a year, I seem to hear The school days at Diamond Rock were not all discipline. Friday afternoon spelling matches quite often attracted visitors. Picnics were frequent on warm days. In the spring the entire school often went out of doors for afternoon sessions. On crisp winter days the pupils would crowd into a neighborhood farmer's sleigh and visit another school to "spell down" its students. [Note 25] The few former pupils used to say that the students of today do not have the fun they used to at Diamond Rock School. When the school closed its doors in 1864, the original deed became void and the property reverted to the former owners, the Wersler family. Time and the elements had their inevitable way with the beloved structure as it stood idle and abandoned. The furnishings which had been donated when the school opened were returned to their owners. For forty-five years it fell into a terrible state of disrepair. The roof collapsed, the windows were broken, the wooden floor rotted. Ruin and decay were its destiny from 1864to 1909.

Diamond Rock School in 1909 before restoration. In 1909 there were still a few in the community who cherished its memories and set about to retore it to its original state. Miss Emma W. Wersler, living on the Diamond Rock Farm nearby, aroused a few friends and undertook the task of restoration. [Note 26] It is related that the restoration of the Diamond Rock School building originated with an entertainment given at Great Valley Presbyterian Church, arranged by Miss Wersler, William Ellis, and John O. Roberts. The proceeds from this entertainment were forty-five dollars. This was the nucleus to restore the school to the splendid condition it is in today. It was quite difficult to arouse interest in the school's restoration, but Miss Wersler persisted. [Note 27] In 1918 the restored building was reopened, and the "Diamond Rock Old Scholars Association was established. (It was renamed the "Old Pupils Association of Diamond Rock" in 1925.) An annual reunion meeting is held every year in June. In 1925 the Association also took over care of the nearby Mennonite Cemetery, which was closely associated with Diamond Rock as many members and pupils had relatives buried there. The Mennonites had completely abandoned the cemetery many years before. [Note 28] How well the secretary knew the interest that had been aroused when, in 1922 with only twenty members, she confidently wrote in her minutes: "As a chartered organization and with the added encouragement of funds given and in prospect for endowment purposes, we have on the whole every reason to look forward with optimism to the continuation of the progress of present attainment." [Note 29] A few years later, she expressed it: "In the passing of this meeting we were impressed with the thought that in the preservation of this little building we in a measure assume the responsibility of the ideals and principles as exemplified in the solidity of these walls placed here stone by stone so carefully by those sturdy builders of the long ago." [Note 30] Since the restoration began, there have been many who have become interested in the preservation of the building and surrounding grounds, and the short byroad which formerly cut through the property was closed, thus preserving the grounds entirely. The stones for the wall were taken from the old Mennonite Church which had been demolished. [Note 31] In 1928 a new door was acquired for the school, with the upper part of glass being protected by an iron grille. The same year the Twin Valley Garden Club propagated cuttings from the old boxwood bush of the original Diamond Rock Farm, owned by the Wersler family, and planted them around the grounds: in later years, unfortunately, they were removed by "passerbys". [Note 32] In 1930 a marker or tablet was placed in a conspicuous position for the benefit of those going past the old building. [Note 33] In 1932 a gift of the deed to the property, from Miss M. Ella Wersler and George B. Wersler, took place at the annual meeting. The deed, together with the original deed of 1819, was displayed on a table for inspection. [Note 34] As the interest and membership of the Old Pupils Association grew, so the outside interest grew also. Many families of the former pupils and teachers returned books, copy books, slates, and the many other interesting items that can now be seen at the school. In 1942 an organization of well-behaved young people held their monthly 4--H Club meetings in the school, under the direction of Joseph Oberle, the Chester County Agricultural Extension Agent. [Note 35] In 1945 the school was also opened at the request of the Tri-County Concerts Association for their festivities in April of that year, and it was again opened for them in several following years. [Note 36] During warm weather, the school is opened on Sunday afternoons for the benefit of those driving by, enjoying the beauties of the Chester Valley, as well as on Chester County Day in October of each year. Many stop and thrill at what took place in that little octagonal school house on the side of Diamond Rock Hill. In 1818 George Beaver, of Tredyffrin, won local acclaim by giving his neighbors a lease for 999 years for a plot of land for school purposes. He never expected the property to revert to himself or his heirs. The school house that was erected was the nucleus of a school system that has spread throughout the township. Diamond Rock School was the seed from which two schools grew in 1863 — Salem School, near Cedar Hollow; and Walker School, two miles east of Diamond Rock. And from these two schools, the present school system in Tredyffrin is descended. [Note 37] TopNotes 5. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes, 1924., p. 1 6. Interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas, March 29, 1963 8. Interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas 9. The Sunday Bulletin (Philadelphia), Sept. 24, 1961, p. 4 13.Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1930, p. 2 14. Interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas 17. Daily Local News (West Chester), Sept. 23, 1918 18. Messenger (Phoenixville), March 6, 1909 19. Daily Local News. Sept. 23, 1918 20. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1930 22. Interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas 23. Daily Local News. Sept. 23, 1918 24. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1934 27. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1928 28. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1925 29. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1926 30. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1929 31. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1927 32. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1928 33. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1930 34. Annie M. Dunlap, Minutes. 1932 35. Interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas 37. Public Ledger (Philadelphia), May 20, 1931 TopSources Personal interview with Harriet Detwiler Thomas Old Pupils Association of Diamond Rock: Secretary's Minutes, 1924--1934 I. M. Beaver: History and Genealogy_of the Beaver Family, Reading, 1939 Raymond A. Elliott: Diamond Rock Octagonal School, West Chester, 1950 Joseph S. Walton and G. W. Moore: The History, Geography and Government of Chester and Delaware Counties, West Chester: Chester County Publishing Co., 1893 The Sunday Bulletin (Philadelphia), September 24., 1961 Daily Local News (West Chester), September 23, 1918 Messenger (Phoenixville), March 6, 1909 Public Ledger (Philadelphia), May 20, 1931 Various clippings in the Diamond Rock School, including Wilhelmina D'Arcy, "Going to School in an Octagon" "Diamond Rock School, Interesting Sketch of Tredyffrin's Old School" "Octagonal School" "Octagonal School and the Influence of Hardy Scot"

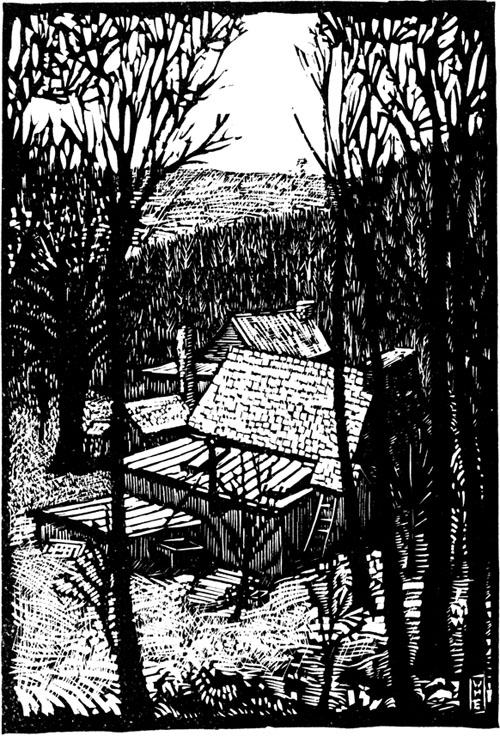

"Diamond Rock Hill", by Wharton Esherick, c. 1923 with the farm house and barn he used for a studio. |