|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 26 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 1988 Volume 26 Number 3, Pages 105–116 A Legacy of John Alden Mason

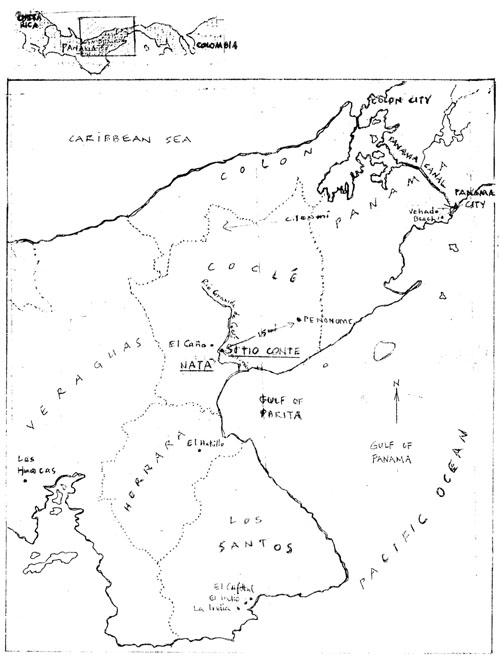

RIVER OF GOLD : Precolunmbian Treasures from Sitio Conte The country of Panama runs generally east and west, despite the fact that it connects North America and South America. (You may remember how surprised you were when you first learned that the Atlantic entrance to the Panama Canal at Colon is west of the Pacific entrance at Panama City.) Along the center of the country runs a ridge of mountains, with rain forest on the Atlantic side. On the Pacific side, however, there is an alluvial plain which has a dry season of three months, from January to April. The rest of the year is the rainy season, when the rivers coming down from the mountains wander gently over the plain. The Rio Grande de Code [see the map on the next page] habitually did just this, but additionally it sometimes changed its course, cutting new channels. Shortly after this happened in the early 1900s, children near Sitio Conte were seen playing marbles with little yellow beads that looked like gold. Stories about this circulated locally, but attracted no widespread attention. Bone fragments and colored pottery sherds were also being found in the new river banks. The Rio Grande de Code had cut through an ancient Indian cemetery! In 1927 flood conditions were more severe than usual, with log jambs in the old channels adding to the problem. New and deeper channels were formed, and soon afterwards large quantities of gold ornaments began to appear in the open markets of Panama City. Now news of the phenomenon spread, and members of the archaeological community began to take note.

What was the connection between these events and Tredyffrin and Easttown? It was John Alden Mason, who for many years lived in the gambrel-roofed house at 725 Conestoga road in Berwyn. He was an early member of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club and its president in 1944. (He was the editor of the Quarterly for thirteen years, from April 1954 until October 1967, only a month before his death at the age of 82!) He was also the director of an archaeological expedition to Sitio Conte in Panama in 1940. Dr. Mason was born on January 14, 1885 in Germantown, the son of William Albert and Ellen Louise [Shaw] Mason. From Conrad Wilson, also an early member of the club, we have learned that the "John Alden" part of his name is truly appropriate; he actually was descended from John Alden and Priscilla Mullens, not only once but several times. He was also related to several other Mayflower passengers, and was a member of the Mayflower Society. (I would like to add at this point that we are indebted to Miss Virginia Beggs, of the Radnor Historical Society, for this information. She had long been associated with Dr. Mason at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of the University of Pennsylvania, hereinafter referred to simply as the University Museum, and very thoughtfully wrote to Conrad Wilson, now living in Vermont, to obtain material for this account.) Conrad Wilson went on to say, "Alden had a brother, and it was predicted that both would end up in prison because they were wild as young persons. [In fact,] his brother became an admiral in the Navy, and Alden became an internationally famous anthropologist!" (So much for predictions!) It was while these two boys were "wild" youths that the Rio Grande de Code was starting to cut its new channels, and thereby provide the background for the exciting archaeological expedition that was later to be led there by Dr. John Alden Mason. In 1903 Alden Mason graduated from Central Hign School in Philadelphia. He then went to the University of Pennsylvania where, in his sophomore year, he took the first undergraduate course in anthropology ever offered by the University. He received his undergraduate degree from Penn in 1907, and immediately started graduate work there and, later, studied at the University of California. At Penn, he came into contact with Frank G. Speck, an anthropologist whose special field was the Indians of northern New York state, and with the famed linguist Edward Sapir. In his studies at Berkeley he worked under the great anthropologist Arthur Kroeber, whose broad interests and knowledge also influenced the young man. As Alfred Kidder, in the October 1968 issue of Expedition, the journal of the University Museum, wrote, "Mason was one of the ever decreasing group of general anthropologists, trained before the days of extreme specialization, who was excellent in nearly all branches of their profession." Dr. Mason received his Ph.D. from the University of California in 1911. In that same year he was chosen to represent the University of Pennsylvania for two seasons in Mexico, in a joint enterprise called the International School of Archaeology and Ethnology. He then spent more than a year with the Puerto Rico Survey. Both of these experiences brought him in close touch with Franz Boas, of Columbia University, another of the early founders of American anthropology. Between 1910 and 1917 Mason went into the field eight times, a tremendous record. Later, despite his heavy museum duties from 1917 to 1955, he managed to participate in sixteen more field trips. Their geographical range covered five states in the United States -- Utah, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas - and six states in Mexico, as well as Puerto Rico, Colombia, Panama, and Guatemala. He was no armchair archaeologist! In 1917 he went to the Field Museum in Chicago, to become the assistant curator of Mexican and South American Archaeology, a position he held for seven years. Four years later, in 1921, he married Florence Roberts. They had a son, also named John Alden, who will figure in our story later, and a daughter Kathleen. From the publications he started to produce as early as in 1912 one can see his interest in living people, and especially in the Indians of the Americas, as well as in archaeology. His focus in his early years was primarily their languages. Another of his special interests was American folklore, and he was on the Council of the American Folklore Society for many years. The confidence of his peers in his literary abilities was evinced in 1940 when he was asked to become the Editor of the American Anthropologist. In 1924 he left the Field Museum and went to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. There he was the curator of Mexican Archaeology, a position similar to the one he had held in Chicago. However, the very next year he left there and came to the Philadelphia area to become a member of the staff of the University Museum. He was immediately named the curator of the American Section. It was no mean assignment, as it meant he was responsible both for all the research work and for all the artifacts -- from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego! In 1923 he chose as his graduate student assistant a young man named Linton Satterthwaite, who later wrote, "I was Alden's assistant for 25 years until he became Emeritus Curator of the American section in 1955. The fact that I loved him throughout those years, and since, and in that relationship, speaks for itself as to his intimate kindness and generosity as a person. There was a fundamental drive to be of service, to help the other scholars, and especially the younger would-be scholars." We have so far been considering for the most part the professional credentials and attainments of Alden Mason, but the man was many-faceted.

Dr. J. Alden Mason Mason was an ardent gardener. He and four other "flower lovers" (his own description) met at the Berwyn Library on October 18, 1933; they were there to form "The Men's Garden Club of Berwyn", though it soon became known as "The Men's Chrysanthemum Club" for good reason. In an article in the April 1956 [Vol. IX, No. 1] Quarterly Mason reported, "A few years before, the women had founded the Berwyn Garden Club, and the men felt they [too] should be organized. Two members of the women's group, Mrs. Mildred Bradley Fisher and Mrs. Henry C. Potts, also attended, probably to give the boys some warning and advice on the formation of such a club. "Apparently any precautionary notes that were sounded by these ladies were not taken to heart, however, as, Mason continued, "A week later the men met again at the Potts home, and with considerable temerity decided to hold a chrysanthemum show at once." As it turned out, that first show was a success, and others followed it annually. Some of the members also raised dahlias, and exhibited them at subsequent shows. (You can sense Mason's enthusiasm and joy in gardening as you read his article.) This love of plants and flowers overflowed to his friends and co-workers. Miss Beggs has recalled that he gave plants and flowers away, and transported some of them to the Museum. Alfred Kidder, one of his associates at the Museum, in Expedition [October 1968], also noted, "Many of his friends in the Museum, especially the ladies of the staff, will not soon, forget the flowers that he used to bring them, and I have a living memorial of his kindness in the form of a thriving bed of lilies of the valley which were once part of his garden." What was going on back at the Rio Grande de Code during these early years of the 1930s? As we have pointed out, archaeologists had by now heard of the gold objects, the bones, and the pottery in the river banks at Sitio Conte. ("Sitio" means site, and "Conte" is the name of the family which owned the land.) Realizing the importance of the remains being washed away by the river, the family invited archaeologists to excavate the cemetery. The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University mounted an expedition to the site in 1930, under the leadership of Dr. S. K. Lothrop. This field force returned to Sitio Conte in 1931 and 1933, conducting a careful excavation. It uncovered many artifacts of pottery and gold, which Mason later described as "beautiful, artistic and unique specimens from an Indian culture that was heretofore quite unknown". After the 1933 expedition, however, apparently no further work was done at the site by anyone until 1940. As the world political situation worsened in the late 1930s, Mason's life was affected in two very different ways. One result of the World War II years was an increase in the activities of The Men's Garden Club of Berwyn. As Mason reported in his article about the Garden Club, "the club took over the encouragement of Victory Gardens to raise vegetables. All persons with sufficient ground were encouraged to plant, and given advise and help." Prizes were also given for the best gardens. It also affected his work at the Museum. Funds which had previously been allocated for archaeological work in Egypt and Mesopotamia could not be used for that purpose, and were freed in 1939 to be used for work in the Americas. The Mediterranean world was too disturbed for archaeological expeditions. Mason, with his keen interest in Indian languages, hoped to use the grant for a study of nearly extinct Indian languages of western Mexico. (Back in 1918 he had written "Tepecano, a Language of Western Mexico".) But it was not to be. The terms of the grant required that the funds "be spent for the increase of the Museum collections". No project of pure research could be undertaken with them. While this was not only a disappointment to Dr. Mason, but also a loss to the study of American linguistics, it ultimately led to the wonderful exhibit, "River of Gold : Precolumbian Treasures from Sitio Conte", at the University Museum! But there are some other facets of Mason's life to be considered before we discuss the expedition to Panama. In 1952 the Unitarian Church of Delaware County was founded in Springfield. It developed several local discussion groups which met regularly. One of the most active of these was the Main Line group, which met in the Radnor-Paoli area. "By 1957," Mason wrote in the October 1966 [Vol. XIV, No. 2] issue of the Quarterly, "it came to be felt that there might be enough interest in Unitarianism in this area to support a new fellowship. "The attendance and enthusiasm at several successive meetings in the spring of 1958 in the Radnor-Berwyn-Daylesford area proved this to be true. The end result was the official organization of a local fellowship on May 25,1958 at the old Berwyn Methodist Church on Main Avenue. Thirty-five people, including Alden, who was of an old Unitarian family, and Mrs. Mason, were among the founder members. The new Fellowship leased that church and its associated parsonage, but it was soon realized, as Dr. Mason observed, "that church (rather than fellowship) status, a resident minister, and our own building were goals for the future". In the meantime, for five years there was a different speaker each Sunday, and men and women from various fields of work and knowledge spoke. Senator Joseph Clark and Norman Thomas drew the largest congregations. (A poignant note is struck by the fact that the Reverend James J. Reeb, the martyr who was murdered at Selma, Alabama, spoke several times, and "was even under consideration as a permanent pastor.) In 1960 the Church acquired the four-acre McMichael property on Valley Forge Road in Devon, close to the old St. David's Church, and on April 30,1961 the first service was held in the new church home. Two years later a parsonage had been built, and the Reverend Mason McGinnis was installed there with his family. In 1952 Dr. Mason was also asked by Pelican Books to write an account to be called The Ancient Civilizations of Peru. I again quote from Linton Satterthwaite: "Characteristically, "Alden was unwilling to tackle the job on a mere library research basis. Fortunately, the Viking Fund financed an extended field trip specifically in preparation for writing this book," It was published first in 1957, after his retirement from the University Museum. It went through many printings, and was revised in 1961 and again in 1968. It has been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and German. Mason himself took all the photographs of the Peruvian archaeological sites used as illustrations. These photographs show another of his abilities -- and excellence of execution. They also remind me of a time I saw Dr. Mason. In about 1950, when our Kenneth was six years old or so, we learned that a circus was coming to Berwyn, and would be unloading from its train and setting up on the old Fritz field that is now the Berwyn-Main Line Apartments property -- at 6:00 a.m.! Wouldn't it be a great idea for me to take Kenny down to see this exciting operation!? When we arrived at the field the roustabouts were "doing their thing". But something else caught my eye. Circling around them, slowly in the morning mist, were two short, quiet figures in brown coats. They moved as one, so intent on their project that they never noticed us as they assumed one position after another to photograph the various circus activities. It was, of course, Dr. and Mrs. Mason! From Peru to the circus at Berwyn -- another facet of a wonderful person! The "River of Gold" exhibit at the University Museum featured a number of artifacts excavated by the expedition to Panama led by Dr. Mason in 1940, seventeen years before the publication of his book on Peru. When the Spanish conquered the Code area in 1516 to 1520 it was occupied by numerous Indian chiefdoms. There was continual warfare among them, for more land to grow more food and for more rivers from which gold, coming down the streams from the mountains, could be panned. The society was divided into two classes. The upper class consisted of the paramount chief and his family and his sub-chiefs and their families. In the lower class were the commoners. The sub-chiefs had to supply the head chieftan with food, warriors, and gold -- and you can guess who supplied the sub-chiefs with these! (The Spanish wrote about the society while destroying it.) From the types of artifacts and their placement in the graves, one can see that this had been the socio-political structure here for some 1000 years. One of the extraordinary things about the "River of Gold" exhibit is that it could take place at all! The Spaniards' administrative center was at Nata, right across the Rio Grande de Code fromn Sitio Conte. Nata, before the Spanish conquest, had been the seat of the controlling chief of the Code region surrounding Sitio Conte. How did the conquerors, who looted so many gold objects from nearby cemeteries, miss the Sitio Conte cemetery which was so near to their official center? While Mason thought that the cemetery had been used almost up to the date of the Conquest, more modern and sophisticated dating techniques indicate otherwise. Burials were made there only from about 450-750 A.D. to 900-1100 A.D., so the graves were quite deep in the soil. In addition, there were no surface indications of them. The land looked exactly like the other rolling hills -- until the river cut the new channels. A very important aspect of the exhibit is that its artifacts were taken from the graves with precise archaeological methods. There were careful surveying and plotting, the making of scientific notes, some 200 photographs and about as many feet of motion picture film, both in color and black and white. All phases of the life and work at the camp were thus recorded. And, secondly, the gold objects were found in association with pottery, allowing some rough dating of them. While artifacts of gold and stone by themselves cannot be dated, pottery can be. So not only can we appreciate the beauty of the objects, and the associated inspired technology, but we have glimpses into the life of the ancient inhabitants. I use the term "glimpses'* because, as Mason pointed out, since the deeper graves were below water-level the greater part, of the year the artifacts had been exposed to moisture for long periods of time. He wrote that the human bones were "so fragile that it was impossible to preserve them for scientific study" and that while the water had no effect on the stone or gold objects, "the pottery was often soft". The carved bone objects were thus wery fragile, and the colors on the painted pottery washed off very easily. In addition, as Mason also noted, "So numerous were the graves that in digging one of the deeper ones they were almost certain to cut through one or two at a higher level, and sometimes the finer objects in the graves that were cut through were kept and placed in the lower new grave." These factors combined to make scientific study of the sequence of types "extremely difficult". No one can tell the story of the expedition as well as its director, Dr. Mason himself. Parts of the following description are therefore excerpts from his two articles in the July and October 1940 [Vol. Ill, Nos. 3, 4] issues of the Quarterly about the expedition. (One of the members of the expedition was John Alden Jr., then a senior at Tredyffrin-Easttown High School. He was taken out of school to accompany his father and to help with the excavation, as well as to carry out general duties around the camp.) The trip down from New York City to Panama City was on a "swanky" steamer of the Grace Line. This is Dr. Mason's description of the camp: On arrival at the site two large houses were built with board floors, thatch roofs, and walls of canvas and netting. One of them was used as the headquarters house for dining and work. ... [Members of the Expedition lived in three tents. We also built a kitchen, small piers at the river for the laundress and for bathing, and bought two small native houses for the use of the camp help and for storage. We had an excellent cook who was able to provide delicious food prepared in all possible ways. It. sounds fairly luxurious so far -- but the heat, the insects, and the snakes are yet to come! The temperature was very high, certainly over 100° in the sun every day, but the dryness of the air and the almost continuous trade-winds from the northwest made it very comfortable. The insects, one of the great discomforts of life in the tropics, were very few. On trips outside the camp we were certain to be covered with tiny ticks, but those in the camp enclosure disappeared after a few days. Owing to the dryness of the season there were practically no mosquitoes. Venomous snakes are rather common in the region and we took great pains to keep the paths in the camp enclosure cleared, and always kept at hand the anti-venom and apparatus for treating snake bites, but no member or employee of the expedition was bitten. ... However, the cook was frightened one day by having a very large boa fall on his floor from the roof. Frequently native wild animals were brought in to us and at variois times we had around the camp ant-eaters, armadillos, squirrels, and parakeets. All of these died or escaped except for a little fawn, which thrived, became very tame, and was taken to Panama City. The present population of the country is not great, as it is a non-agricultural, cattle-raising country. The natives live in scattered houses along the river, where they grow corn and other crops for their own use, but are often forced to mcve during the deep floods of the rainy season. They are a mixture of Negro, White and Indian, with the former predominating. It is a pleasure to record the friendly personality and perfect honesty of these natives. Both our expedition and that of the Peabody Museum left gold ornaments in plain view in the ground for several days at a time without, any loss, and nothing whatsoever was stolen from the camp during the entire period. With their sharp eyes they constantly found gold beads and similar objects in the dirt thrown out, and I firmly believe that they turned over to us every piece of gold thus found. They are a happy, though very poor, people, anc' the relationship between them and the members of the Expedition was most cordial. The principal diversion of the people is a celebration or dance, one of which is held at some house in the region at least once a week. The men and women dance by couples, but independently, to the music of a number of native drums and the singing of the rest of the women. At these "Tamboritos", as they are called, enormous quantities of a native beer, made of corn and called "chicha", are consumed. Field work iri the five to six acre cemetery started on January 15, The group had to leave for home in mid-April. By late March they had cut a big trench and encountered thirty qraves or caches, some graves being ten feet square. They contained objects of stone, carved bone and gold, and hundreds of pottery vessels -- but nothing really amazing. Then they came to Burial 11! (In setting up the "River of Gold" exhibit, the artifacts were arranged to reflect their distribution in the three layers of this bowl-shaped grave.) In the first layer of this grave were eight skeletons, surrounded by agate pendants, quartz projectile points, celts (axe-heads) of grey stone, the spines of sting rays, and a few gold bells. Young John Alden later said it was the beginning of the most exciting day of his life. After they had dug down about 18" more, a spectacular sight was revealed. The grave walls were completely lined with pottery, set in plaster, and there were twelve more skeletons, lying in six pairs and covered with pottery vessels. 'Mason wrote, "All of these persons were apparently of some social importance, as almost all of them had some gold ornamentation and one, presumably the chief, fairly blazed with a wealth of gold." This skeleton was covered with great gold discs. Used as "breastplate" plaques, each disc depicted fantastic creatures that combined human and animal charcteristies. The chief also had ear rods, cuffs, bells, beads, pendants, and anklets, all made of the precious metal. On top of this glistening hoard was a large, complex zoomorphia pendant of gold. It had some features of a jaguar, and some of a crocodile. From its mouth came curving streamers of beaten gold; on its back was a large uncut emerald, probably obtained from Colombia or Ecuador, and skillfully inlaid; three gold rings, with suspended wafer-thin gold trianges, were affixed to its back, and the body terminated in two serrated wheels which add an incongruous element to the animal-like figure. These accoutrements were of the type that would have been worn in battle, and Mason believed the other skeletons may have been those of sub-chiefs, all slain in the same great battle. At the feet of the paramount chief lay something that is still a mystery -- a group of tiny gold chisels. We do know from 16th century Spanish accounts that one of the first things a man in this culture had to do upon becoming a chief was to choose his personal symbol, often an animal. This was not only tattooed on him, but also on his warriors so they could be distinguished from the enemy in battle. Therefore it has been suggested that these tiny gold chisels may be ceremonial representations of the copper ones that were used for tattooing. But it has also been suggested that they might be models of the tools used for shaping the gold disc "breastplates" -- or that they even are just toothpicks!

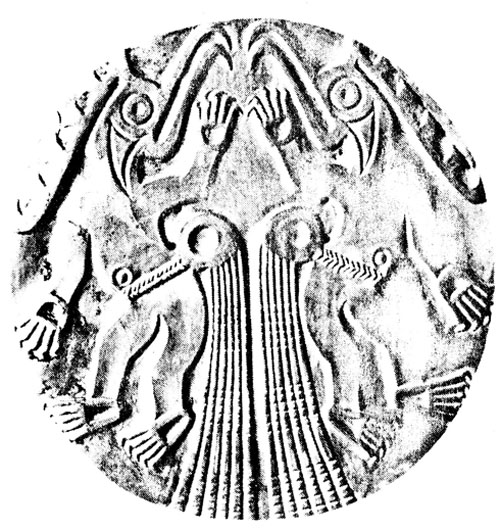

Gold "breastplate" plaques from Burial 11, Sitio Conte

One foot lower down lay three more skeletons, probably of sub-chiefs. In this layer there was also a single great gold disc, as well as gold ear-spools with elaborate finials. These ear-spools were hollow tubes which had been skillfully made out of thin sheets of gold, heated and worked so that even under a microscope it is difficult to identify the seam. Of their gold work, Mason said the "objects are of exquisite workmanship. The technique is of a quality hardly surpassed by any goldsmith." The gold and emerald zoomorphic figure and other items from the second layer of the grave, with their wonderful craftmanship, were featured in the center of the exhibit space. In another case there were little figurines," carved from resin, bone, or from the tooth of the female sperm whale. Their feet, tails, wings, and heads were of gold onlay, and the carvings tend to be more naturalistic than the gold repousse ones, They are, of course, "very fragile though very beautiful and required careful Museum treatment before exhibition". In another section was an exhibit on the technology used to create these "objects of excellent workmanship". Here one could learn how to make a gold plaque or disc by the repcsse method, or make a figurine using the lost wax molding technique, or attain 'a lustrous sheen by depletion" gilding. Actually, none of the objects found in Burial 11 at Sitio Conte was made of pure gold,. In most cases they were of a gold-copper alloy, but by heating the object and then "pickling" it in acidic juices and rubbing it with a fine paste of sand (or crocodile dung) a brilliant gold surface resulted. Mason's estimate of the honesty of the natives has already been cited. So rich and unusual were the finds in Burial 11, however, that the director felt some safeguard should be made. Since the second level had not been reached until about four o'clock in the afternoon, it was impossible to complete the excavation with proper archaeological procedures by nightfall. John Alden Jr. was selected to guard the gold. A cot was brought out for him anc placed beside the grave, and there he laid down to spend the night. With a full moon shining down on the gold, it was a dramatic scene. He stayed awake to appreciate its unique beauty -- as well as to watch for marauders! John Alden Mason Jr. later became a member of the United States diplomatic corps. He now lives in Maine, but came to Philadelphia for the Members' Preview opening of the "River of Gold" exhibit -- a legacy of his father, John Alden Mason, of Berwyn. TopBibliography

Hearne, Pamela

Jones, Paul

Kidder, Alfred II

Mason, J. Alden

Satterthwaite, Linton

Snarer, Robert J, and Hearne, Pamela also Biography of J[ohn] Alden Masor., in Who's Who in Pennsylvania, 1959. Obituary in TEHCQ, Vol. XV, No. 3. Miscellaneous newspaper clippings from files of Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, Pa. Conversation and correspondence with Virginia Beggs. |