|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 38 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 2000 Volume 38 Number 3, Pages 79–92 The Chester Valley Railroad TopPrologue The Chester Valley Railroad had its beginning in 1835. It is of interest to briefly explore the techno- political environment of that time, and to orient the reader to which railroad, of many in this area, we will be talking about. Travelling north from Berwyn on Howellville / Cassatt Road, one first crosses the four tracks of the Amtrak (former Penn Central)Main Line. About a mile further, one crosses the Trenton Cut-off of the now Norfolk Southern (formerly PRR, Penn Central, Conrail). Finally, at the end of Old Cassatt Road lies a bridge over the defunct Chester Valley Branch of the defunct Philadelphia and Reading Railroad; look promptly, the bridge is being removed in the Route 202 highway improvement project. The roadbed of the Chester Valley line ran under the bridge on Contention Lane and atop the rather high embankment behind the strip malls on Swedesford Road. [Note 1] We moderns tend to think of railroads with a sense of powerful prime movers with many cars riding on steel rails. However, the first railroad, in 1602, was horse-drawn, and the prime movers were fueled by hay for many years. Transport of heavy burden, particularly coal or ore, was effected by navigable rivers and canals. [Note 2] In 1823 the Pennsylvania Legislature granted John Stevens a charter authorizing the construction of a railroad from Philadelphia to Columbia, even then anticipating an extension to Pittsburgh and west to Ohio. Although early surveys were made, opposition from canal interests prevented actual construction. A rush to "do something" was ignited by the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Almost immediately the lucrative trade with the West, enjoyed by Philadelphia and Baltimore, began to flow through New York. In 1826 an act was passed repealing the Stevens charter, providing for the start of the Pennsylvania Canal, and incorporating the Columbia, Lancaster and Philadelphia railroad to cover essentially the same route laid out by Stevens. Parts of the line were put in operation, using horse-drawn cars, when completed. The line from Philadelphia to Paoli opened in September, 1832. It is remarked that the State system was viewed as a canal network; the railroad resulted from the discovery, by surveyor Major John Wilson, of insufficient water to support a canal. The beginning of the Erie Canal in 1815 scared the Pennsylvania Legislature into chartering the Schuylkill Navigation Company to provide a navigable waterway from Philadelphia to Port Carbon and its adjacent coal fields. The canal opened in 1825. In the meantime several small railroads were established upstate to haul coal from minehead to the canal. The coal business boomed for the Schuylkill Canal, but canals have a nasty habit of freezing in winter. In 1833 the Legislature passed the enabling act for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. By 1838, regular service had begun between Reading and Bridgeport, with a connection at Norristown with the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown. Thus it would come to pass that the Philadelphia and Columbia on the west, and the Philadelphia and Reading on the east, would become the termini for the Chester Valley Railroad. TopIn The Beginning As the year 1833 opened, the Great Valley region had essentially been passed by, most likely by the circumstances of development. [Note 3] However, the citizens of the Valley had their own transportation needs. In January of 1834 a number of citizens met in Howellville to consider petitioning the Legislature to pass an act authorizing the governor to incorporate a company to construct a railroad from some point on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, passing down the Great Valley, to the Schuylkill River, thence connecting at some point with the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad. The resolution adopted at the meeting put forth a number of arguments as to the superiority of the proposed route over that chosen by the Philadelphia and Columbia, overlooking the fact that the P&C had started steam service between Philadelphia and Paoli in late 1832. Relocating the line would be political folly. On April 13, 1835, the Legislature granted a charter to the Norristown and Valley Railroad company to construct a railroad to run from east of the Brandywine Creek on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, and connect with the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown RR somewhere near Norristown. The company was to begin construction within three years, and complete construction within seven years. The Commonwealth provided itself the right to purchase the railroad at any time within twenty years, adding it to the state-owned system of public works. Following line-location surveys, Downingtown was selected for the western terminus, and Conshohocken for the connection to the PG&N. Support for the adventure was mixed. Farmers in the western end of the valley were less than ecstatic, perhaps because of the proximity of the Philadelphia and Columbia, but certainly because of dissatisfaction with the payments for their right-of-way. Meetings were held in August of 1835, and again during the following January, to voice protest against the damages which they felt at the hands of a "corporate monopoly". This mixed enthusiasm, together with the economic depression of 1837, resulted in disappointing progress in financing and construction. [Note 4] At the end of the seven years stipulated by the corporate charter the construction was not complete. In 1842 the Legislature extended the period for completion another three years. Despite the expenditure of $850,000, by 1845 it was still not completed. The result of this failure was the cessation of operations, and the charter lapsed. TopRebirth Interest in the project continued. By act of the Legislature on April 22, 1850, the effort was revived under the name Chester Valley Railroad. The new charter contained many interesting provisions. The act created, by name, a panel of commissioners whose job was, in turn, to create the new company. Their first task was to convene a publicized meeting of stockholders and creditors of the late Norristown and Valiey Railroad. On presentation of evidence of claim, stockholders of the N&V would receive one share ($50 par value) of new stock for every $100 of previous ownership. Bondholders would receive one share for every $50 due. When the claims had been satisfied, the commissioners would so certify to the Governor who would then, by letters patent, create the new company. The additional stock authorized was 6000 shares at $50 par value. The act also provided that any cars passing from the Philadelphia and Columbia over the CVRR to Philadelphia, or 12 miles east of Norristown, would be charged, and paid into the Commonwealth treasury, the same fare as had they passed only on the State system from Downingtown to Philadelphia. Thus, the Chester Valley Railroa was to be a short-haul railroad. This fee was viewed, correctly, as a "tonnage tax". The act also specified much of the route. The new railroad was to use the route laid out for the Norristown and Valley Railroad from Downingtown to Henderson's marble quarry, presumably now Henderson Road, King of Prussia. [Note 5] From there a new route was to be selected to connect with PG&N at Norristown, and with the P&R at Bridgeport. [Note 6] Furthermore, in the event that the new railroad should connect either directly or indirectly with any road(s) leading to the Delaware River in the direction of New York, the act would become null and void. Time limits were January 1, 1852 for organization; January 1, 1855 for ten miles of operation. Work was started immediately, and on September 12, 1853, the road was opened to public travel. Fifteen days later a banquet was held at the Swan Hotel, Downingtown, to commemorate the occasion. However, it appears that the Chester Valley Railroad company was always viewed as an investment, not as an operating company. On December 31,1852, seven months before opening, the Chester Valley Railroad executed an agreement with the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad company whereby the CVRR agreed to complete their road, including fences, cattle guards, and the depot at Downingtown, and to keep the railroad in good repair for three months; the PG&N agreed to furnish cars and engines, and to do all of the business upon the CVRR, and to keep the road in good repair after the initial three months. The PG&N also agreed to collect all monies for fare and freight, first paying themselves 70 cents a mile for every train mile run, paying over the balance to the CVRR. The PG&N also agreed to keep the books, magnanimously opening them to officials of the CVRR. Thus, even before commencing operations, the CVRR was effectively under lease to the PG&N. It is interesting that one William E. Morris, at the signing, was president of both railroads. At the end of 1853, after three months' operation, the railroad's operating deficit was slightly over $1000, attributed to lack of coal and iron ore freight. Their assets exceeded their liabilities by $45. Capitalization was $871,000 in stock, and $500,000 in mortgage bonds, the latter to become quite significant. In April of 1854, arrangements were made with the PG&N for direct through- service between Downingtown and Philadelphia. The service was sufficiently popular as to elicit letters of praise to local editors. Regardless, before the end of April, the same journals were apprehensive that the railroad was paying little more than the cost of operation, and would not be able to pay the interest on the funded debt. In June of the same year, the stockholders were assessed a total of $17,000 to pay the interest due. In May of 1855, speculation arose regarding possible repeal of the charter clause requiring payment of full fare to the state for all shipments between Philadelphia and the State railway. Repeal of the tonnage tax was signed by the Governor in April of 1856. Net receipts for 1856 nearly doubled from the year before. The annual report of January, 1857, forecasted the opening in March of a branch line to the quarries of the Cedar Hollow Lime Company, and increased tonnage from that source. Apparently debt service remained a problem, since the Solicitor opined that the bondholders could not sell the railroad before 1872, the year of maturity. There was also interest in talk of a new railroad being built from Morrisville to Norristown, connecting the Reading with the Chester Valley RR, with the objective of providing a direct path to New York. There was no mention that such connection would clearly invalidate the Chester Valley charter. As 1858 began, the 5-year operating agreement with the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown expired. Seeking a better deal, the Chester Valley management opened negotiations with the Philadelphia and Reading, signing a lease in the latter part of the year. Although the new operating agreement improved the profitability of the CVRR, the stockholders feeling that the directors had overstepped their authority, passed a resolution requiring the corporate secretary to notify the Reading that the lease was considered null and void. Fortunately, reason prevailed, and the Reading took control. Apart from the fact that the Reading gained an important feeder to their main trunk, they gained a connection to the Pennsylvania Railroad which had purchased the State system in August of 1857. It is interesting that years later the PRR requested use of the CVRR branch to bring rolling stock into "safe harbor" as Lee invaded Pennsylvania. The new arrangement was also profitable to the CVRR. The annual report in January, 1860 stated that the amount received from the PG&N in 1858 was $667, while the amount received from the P&R for 1859 was $12,174, a handsome increase. However, they were still not paying the bond coupons. It appears that the early 1860s saw some payment to the bondholders, but no mention is seen of dividends. Presumably the stock price fell. A notice in the American Republican newspaper in West Chester warned stockholders against sacrificing the company's stock, since "arrangements" would be carried out in short time to bring the stock up to the $50 par. Arrangements not withstanding, in 1869 stockholders were assessed 7-1/2 cents a share to pay taxes. Business was fairly good. A schedule from 1869 shows three trains a day, each direction, between Philadelphia and Downingtown with 16 stops along the way. A single passenger train left Downingtown at 6:00 AM, returning from Philadelphia at 4:30 PM, clearly a commuter train. In fact, the schedule advertises commutation, school and excursion tickets at reduced rates. The travel time was 2-1/2 hours. Perhaps this was the start of suburban living in the Great Valley? The remaining trains were mixed freight and passenger. The schedule called for trains leaving Philadelphia at 12:45 PM, and Downingtown at 1:00, with a meet at King of Prussia at 3:07; perhaps a toddy at the Inn? There seems to be a paucity of reports on the fortunes of the CVRR during the 1870s. One presumes that traffic continued to increase, both passenger and freight burden, yet it appears neither interest nor dividends were paid. Since the Reading was the major creditor and operator of the CVRR, its management provided a good role model for successfully running a railroad without satisfying financial obligations. In 1869, Franklin B. Gowen became president of the Philadelphia and Reading, and embarked on a decade of corporate adventurism ending in bankruptcy for the railroad in 1880. [Note 7] That same year Gowen became a director of the Chester Valley. F. B. Gowen was not afraid to spend money, especially someone else's money. The early 1880s saw many improvements to the Chester Valley Railroad. The Downingtown depot was renovated in 1880. In 1882, new locomotive watering facilities, and a new turntable, were installed at Downingtown. Surveying was done for double-tracking, although the trackage was not laid. In 1883 a bridge was built across the railroad in East Whiteland. In 1 884 an additional locomotive was added, built by apprentices in the Reading shops for the 1876 Centennial. In 1885 another passenger train was put on the road; by this year the Philadelphia to Downingtown travel time had been reduced to one hour and twenty minutes. In 1886 CVRR stock rose to $58 a share amid rumors that it was being quietly bought up. By May of 1887, A. J. Cassatt [Note 8] had secured the majority of the stock of the Chester Valley Railroad. It was supposed that he bought it in the interest of the Pennsylvania Railroad, undoubtedly correct, and that the purpose was to extend the road to Trenton, thereby shortening the PRR route from New York to the West by about 25 miles. However, ownership could not be so easily transferred. By this time the CVRR was in the hands of Colonel James Boyd, trustee for the bondholders, with full authority to sell. At the time, the indebtedness amounted to $500,000, plus 25 years' interest. The Philadelphia and Reading owned $252,000, and A. J. Cassatt $61,000 in bonds. The Reading itself was in the hands of receivers, being directed by a voting trust organized by J. P. Morgan; the president was Austin Corbin, elected president in 1886. Apparently only Cassatt had hard money. In June, Cassatt and Corbin separately wrote to Boyd demanding the sale of the Chester Valley to pay the mortgage obligation. Colonel Boyd, mortgage trustee, petitioned the U. S. Circuit Court for permission to sell the road without going through foreclosure proceedings. There were 55 bondholders owning $500,000 of 7% bonds, and 215 stockholders owning $871,900 of stock. A Special Master recommended sale, and the road was put up for auction on January 17, 1888. A bidding war developed between (representatives of) Austin Corbin and A. J. Cassatt; Corbin won with a final bid of $555,000. The Chester Valley Railroad passed out of existence; after reorganization it became the Philadelphia and Chester Valley Railroad, commonly called the Chester Valley branch of the Reading. Previous speculation that A. J. Cassatt wanted the Chester Valley to shorten the freight run from New York to the West soon proved correct. In August of 1889 survey parties were active in the vicinity of the Philadelphia and Chester Valley, and properties were being purchased by PRR in the vicinity of Glen Loch. The Trenton Cut-off of the Pennsylvania Railroad opened for operation in 1892. It left the New York Division at Trenton, rejoining the Main Line at Glen Loch. This freight-only section parallels the Pennsylvania Turnpike through Montgomery County. At Henderson Road in King of Prussia it parallels the (old) Chester Valley with a clearance of only a few yards until the Schuylkill Expressway is crossed; both bridges still standing. The separation then widens to about a half mile until the Chester Valley heads toward Downingtown, near the end of Old Cassatt Road. Although the Chester Valley is gone, the Trenton Cutoff remains in active service today -though reduced to a single track. Advantages began to accrue now that the Chester Valley was truly part of a Class A railroad. The Reading was one of the earliest roads to install telegraph service (1847) for train control, making the service available to adjacent communities.In 1888 poles began to appear along the Chester Valley, even before the filing of the deed of transfer. The telegraph was the Internet of the day, and helped to open up the Valley. Further improvements were made in 1892. In May, newspapers reported the decision to build an overhead bridge, costing $10,000, to eliminate a grade crossing of the PRR, Reading, and Waynesburg railroads at the Chester Valley depot in Downingtown. [Note 9]

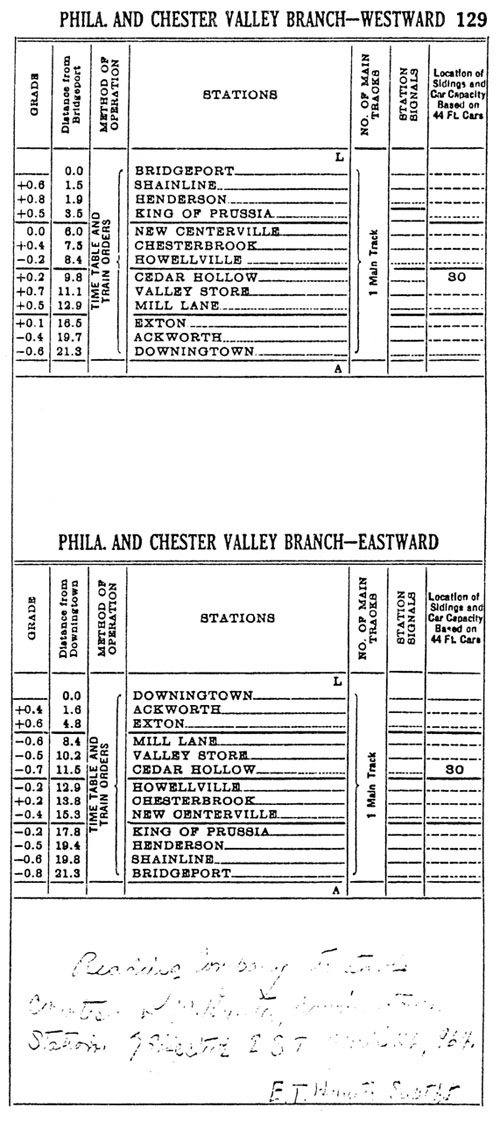

A page from Reading Company timetable of April 26, 1964 showing Phila. and Chester Valley Branch information. (See also Quarterly, Vol. 29, Location of No. 1, January 1991, pp. 39-40, for timetable issued December 1906.) In August a new locomotive, the Shaw, appeared, reportedly doing a certified speed of 57 miles an hour, and without visible smoke (however, this locomotive does not appear on the Reading's list of notable motive power). The year also saw proposals to replace the iron rails with steel. Iron is very brittle under impact, and does not permit the higher speeds allowable with steel; 85 or 90 pound rail was suggested. Rail, tie, and ballast replacement was begun in 1893. The benefits of ownership by a major railroad are also accompanied by their woes. In 1890 Austin Corbin resigned as president of the Philadelphia and Reading, to be succeeded by A. A. McLeod, as adventurous as Gowen. In 1892 the Reading leased the Lehigh Valley Railroad, the Central New England Railroad, and the Boston and Maine. In January of 1893, Philadelphia's Reading Terminal opened. In February, the Reading went bankrupt for the third time, which event was a precursor of the so-called Panic of 1893. Although the reorganization, supervised by J. P. Morgan, was complex, by the end of receivership in 1897 the ambitious expansion had been relinquished, the Reading Coal and Iron Company had been sold, and operational equipment was purchased by a banking syndicate and leased back to the (new) Reading Railway. This procedure would be frequently used by financially troubled railroads in later years. The Philadelphia and Chester Valley, together with many other small roads, remained a separate company, mortgaged to the Reading. It formally became part of the Reading system in 1945. The Chester Valley continued to provide local service to the Great Valley. Stone from the quarries comprised heavy burden, with produce and mill products headed to Philadelphia, and farm staples and building supplies flowing in the reverse direction. After its 1897 reorganization, the Reading developed several very fast locomotives which made national speed records on their Atlantic City run. The Reading began to emphasize fast passenger service. Their adopted child, the Chester Valley, provided commuter service in the Valley, probably benefiting from the new reputation for speed. As late as the mid-thirties, there were two trains a day in each direction, but high-speed, more frequent service on the PRR out-classed any competition from the Chester Valley. Until about 1970, there were still short freight trains on the Chester Valley branch - as many as six a day. However, it was clear that trucks were stealing local traffic. In April of 1976, Conrail took over the Penn Central and the Reading, and the Chester Valley branch was abandoned. [Editor: In fact, continual if unscheduled freight service was provided by Conrail on the Chester Valley right-of-way into the early 1990s] TopEpilogue For several more years the Chester Valley tracks remained in place. For a short while PECO used the eastern end to move transformers to the Berwyn maintenance complex, until heavy-duty trucks ended that requirement. Some speculation turned on using the right-of-way for a new light rail transit line. However, PennDOT eliminated the bridge on Swedesford Road near the Church Farm School in 1995 simply by filling in the cut, and paving over; the bridge over Devon State Road was removed at about the same time. The eastern portion of the right-of-way is being leveled for the Route 202 improvement. The remaining properties of the Reading Company have been sold to fund an entertainment business. Mickey Mouse lives! TopNotes 1. Other vestiges of the old roadbed can be seen. There are two bridges, side-by-side, over the Schuylkill Expressway just east of the Route 202 exit; one is for the Trenton Cut-off, the other for the Chester Valley. The high banks on each side of Devon State Road, about 50 yards south of Swedesford Road, were the abutments for a Chester Valley bridge removed just a few years ago. Another bridge still remains over West Swedesford Road, immediately east of the Route 202 overpass. 2. Eventually the Industrial Revolution was driven by steam; 1769 saw the first steam tractor, 1804 the first steam locomotive, and in 1825 the Stockton and Darlington (England) became the first steam- powered railroad. Even here the objective was to haul coal from mine head to the nearest canal. In 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester (England again) went into operation, hauling passengers, over the fierce objection of entrenched canal advocates. "Canal fever" was also rampant in America. William Penn himself saw the connection between the Susquehanna and Schuylkill Rivers by way of Tulpehocken Creek and the Swatara, surveyed in 1762 by David Rittenhouse and William Smith. Nothing much was done while we fought a revolution and a second war with England. A single event lighted many fires; in 1815 construction began on the Erie Canal which became operational in 1825. Since the major interest of port cities was trade with "the West", Philadelphia and Baltimore suddenly saw New York as a major threat to their trade. In 1815 the Pennsylvania Legislature incorporated the Schuylkill Navigation Company to construct a navigable waterway, along and/or using the river, from Philadelphia to Port Carbon in order to carry coal. Opening in 1825, this canal demonstrated the great importance that the coal trade had for the city. Eventually it would become the route of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. 3. Several authors have asserted that Chester County citizens believed that the location of the State railroad, the Philadelphia and Columbia, was influenced by Gen. Joshua Evans who owned and lived at the Paoli Tavern. That may be true, but it does not mean that the Great Valley was a superior route. There are several technical, as well as political, reasons for selecting the ridge route. For example, it had already been surveyed by John Stevens in 1825. Also, the existence of taverns was a technical plus in the day of horse-drawn railroads. However, after the steam locomotive became ubiquitous, the Belmont Plane was a continuing problem. In 1835 the West Philadelphia Railroad was incorporated to leave the Main Line at Ardmore, reaching the Schuylkill just south of Market Street. Because of financing difficulties, it was taken over by the Canal Commissioners, and finished in 1850; then, the onerous Belmont Plane was abandoned. 4. Two young men who had been awarded contracts for construction, including grading one section in Tredyffrin, were Coffin Colket and John O. Stearnes. They were each born in New Hampshire, and had formed a partnership under the firm name of Colket & Stearnes, an association which lasted several years.In 1836, when Colket was 27 years old and Stearnes was 31, they boarded with William and Sarah (Pennypacker) Walker at Walkerviile (later Centreville). There they met their future wives, daughters of the household Mary and Margaret, in time becoming brothers-in-law. In his autobiography, Gov. Samuel W. Pennypacker wrote that his grandfather, with the stability and associations of a prosperous Chester County farmer, commented, "I do not understand why William Walker permits his daughters to marry those wandering railroad men." They each became wealthy. Colket served as president of the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad. Stearnes reached the presidency of the Central Railroad of New Jersey.In 1855 a third Walker daughter, Emma Jane, wed Winfield S. Wilson, who followed Colket as president of the PG&N. By 1883 Wilson owned the property adjacent to Chesterbrook Farm, recently acquired by Tredyffrin Township for a recreational park. 5. Although the act of the Legislature provided for claims of the stockholders and bondholders of the Norristown and Valley Railroad, the aggrieved landowners saw things differently. At a meeting on June 11, 1850, those landowners whose property had been used by the N&VRR asserted that the property and improvements thereto reverted to their ownership when the charter was forfeited. Since the Chester Valley was to use this right-of-way, and the act provided for compensation for the taking of property, they resolved that they had a valid claim against the CVRR. 6. The Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown's northern terminus was at Norristown. The Philadelphia and Reading's southern terminus was at Bridgeport. Thus, the connections specified for the Chester Valley gave it a route upstate and one to Philadelphia. Although it had access to the Philadelphia and Columbia at Downingtown, there was no connection or interchange track. On August 1, 1857, the Pennsylvania Railroad purchased the State system. 7. Franklin Benjamin Gowen was president of the Philadelphia and Reading from 1869 to 1881, and from 1882 to 1886. It was a time of high adventure for the Reading. Gowen leased the Schuylkill Navigation Canal; created the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company (mining); began construction of a shipyard at Port Richmond in Philadelphia; convicted and hung the leaders of the Molly Maguires; smashed the Workingmen's Benevolent Association; leased the Jersey Central; and established an ownership position with Tidewater Oil company. In his spare time he started construction of the South Penn Railroad, expected to compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad, but terminated by the conniving of J. P. Morgan. Today the Pennsylvania Turnpike runs through tunnels bored for the South Penn. 8. Alexander J. Cassatt, a civil engineering graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, entered the employ of the Pennsylvania Railroad as a rodman in 1861. By 1873 he had become general manager of the lines east of Pittsburgh and Erie. In 1880 he became First Vice President, but in 1882 he resigned at the age of 42, ostensibly to raise horses at Chesterbrook Farm in the Great Valley. However, he remained a director of the Company, and held that position in 1888, the year of his bidding war with Austin Corbin, president of the Philadelphia and Reading. Cassatt was president of PRR from 1899 to 1906. He is best known for his extension of the Pennsy into Manhattan, thence out to Long Island. In 1900 he bought controlling interest in the Long Island Railroad, of which Corbin had previously been president. Cassatt is one of the most admired of the PRR executives. A larger- than-life statue of him surveys the entrance to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania at Strasburg in Lancaster County. 9. Maps from the 1883 Breou Farm Atlas show the Chester Valley Railroad approaching the Main Line of the Pennsylvania through East Caln about 1/8 mile west of the present Ackworth Station Road. From there into Downingtown the CVRR and PRR run side by side, essentially sharing the same right-of-way. At Downingtown, the CVRR connected to a wye shown variously as the East Brandywine and Waynesburg, or the Waynesburg Branch, of the PRR, running toward the north. All three railroads crossed Brandywine Avenue where the CVRR had its depot. At Frazer Station there was a three-way junction on the PRR. The Main Line continued toward the west. Joining from the south was the West Chester Branch of the PRR. Headed north was the Phoenixville and West Chester Railroad. The latter crossed the Chester Valley about 200 yards east of the Sweeds Ford Road (as spelled on the map) bridge near Church Farm School in West Whiteiand township. It is remarked that, as of 1892, the Chester Valley made the following scheduled station stops: Bridgeport, Henderson's, King of Prussia, Maple, New Centerville, Garden, Rennyson's (later Chesterbrook), Howellville, Paoli Road, Cedar Hollow, Lees, Valley Store, Malins, Mill Lane, White Horse (later Planebrook), Glen Loch Summit, Exton, Oakland (later Whitford), Ackworth, and Downingtown. Although the CVRR and PRR were in close proximity at Downingtown, there is no map evidence of any interchange track; thus, through-goods would have had to be off-loaded. Between Paoli Road and Cedar Hollow stations there was a wye connection leading to a very long spur to the limestone quarries at Cedar Hollow on the border of East Whiteiand, Charlestown, and Tredyffrin. In addition, a quarter-mile siding, able to accommodate thirty 44-foot cars, was located at Cedar Hollow station. Some other stations had a siding long enough to permit placement of a market car for use by adjacent farm owners. TopAcknowledgment At the time of his death Bob Goshorn was preparing an article about the Chester Valley Railroad. To support his research he had collected copies of many newspaper pieces of historic import. This current paper is based in majority measure upon the material assembled by Bob. TopAdditional References Holton, James L, The Reading Railroad : History of a Coal Age Empire, Volume 1, The Nineteenth Century. (Garrigues House, Laury's Station, Pa., 1989) Alexander, Edwin P., The Pennsylvania Railroad : A Pictorial History. (W. W. Norton Co., New York, 1947) Burgess, George H. and Kennedy, Miles C, Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1846-1946. (Pennsylvania Railroad Company, Philadelphia, 1949) Chester County Planning Commission, Historical Atlas of Chester County, Pennsylvania. (Chester County Planning Commission, West Chester, 1971) Jensen, Oliver, American Heritage History of Railroads in America. (American Heritage Wings Books, Avanel, N.J., 1993) Pennypacker, Samuel W., The Autobiography of a Pennsylvanian. (J. C. Winston, Philadelphia, 1918)

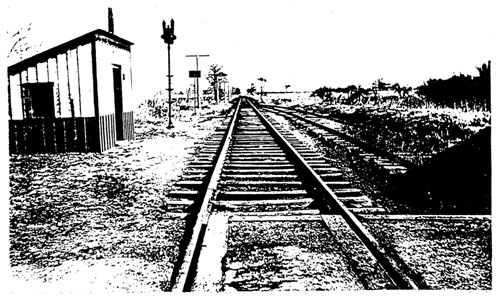

Maple Station of Chester Valley Railroad 1932

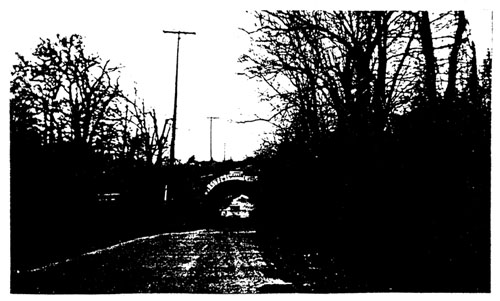

Chester Valley Railroad crosses Swedesford Road at Howellville 1964 |