|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 43 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Spring 2006 Volume 43 Number 2, Pages 53–61 THOMAS JONES Hint for using the footnote reference links: Using the “Back” feature of your browser will return to the previous [Note] link location after you read the footnote. The Delete (Mac OS) or Back Space (Windows) keys often perform this function.

Thomas Jones was a carpenter and farmer of Tredyffrin Township who died in 1765 or 1766. He lived near what is now known as Stirling's Quarters, and may have built and resided in the original part of the house. When he died Thomas owed money to a large number of creditors. Eleven creditors sued him and his estate (see the Appendix for details). The family engaged a lawyer to defend the suits. It is clear from the estate documents that there were further creditors in addition to those who used the courts to try to recover their money. In the first stage of settling his estate his land was surveyed and sold off. His personal property was then valued, and sold at an auction—called a vendue at that time. The accounts of his estate [Note 1] and the list of the personal property provide the basis for this article, which investigates the life of a farmer and carpenter from colonial times. This article covers the economic situation at the time, the Welsh influence on the area, the John / Jones family, the law of property, farm crops, woodworker's tools, cooper's tools, and household goods.

All the monetary amounts in this paper are pounds, shillings, and pence. There were 12 pence to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound. These are Pennsylvania pounds, which were worth somewhat less than pounds sterling. As a measure of prices, one can roughly estimate that a semi-skilled person could earn one pound a week. In 1765 the colonies were in the grip of a recession. They had prospered in the French and Indian War, since extra credit had been provided by merchants in the United Kingdom to help facilitate trade. The colonies actually provided provisions to both sides, much to the annoyance of the British. They thought the war could have been concluded much earlier if it were not for this trade. The war ended in 1763 and the economy subsequently went into recession. It is not clear how this recession contributed to Thomas' indebtedness.

Land was originally reserved by Penn's administrators on the west side of the lower Schuylkill River for Welsh settlers. The north-east boundary of this tract goes through Valley Forge National Historical Park, and the northern boundary is the north boundary of Tredyffrin Township. Tredyffrin Township was originally settled mainly by Welsh. The traditional means of naming by the Welsh was not through a surname, but by reciting the male genealogy—normally just one generation. This was also the case in some Scandinavian countries. So David ap Evan means David the son of Evan. At some stage one of these names became the family name. There were also contractions. For example, Prichard is suspected to arise from ap Richard and Bevan from ap Evan. This explains why a lot of Welsh surnames are also used as first names. These family names were then Anglicized with Davis and Davies, for example, arising from David. In the case of Thomas, the family name of John was Anglicized to Jones and the two names were used interchangeably for many years. Thomas' father, Griffith John, lived from 1671 to 1753. Griffith John and his brother Henry, were early settlers in Tredyffrin which was organized around 1707. Griffith arrived from Wales in 1712 and was appointed the deacon to the Great Valley Baptist Church which had been founded the previous year. Thomas had three brothers, Samuel, William, and John, and one sister, Margaret.

Jones Barn, before deconstruction When Griffith and Henry John arrived in the area, John Havard had already purchased—in 1708—a large area of land of 800 acres, centered in what is now Chesterbrook. Griffith purchased land to the west of the Baptist church and south of the Havard land. Griffith and Henry also purchased land adjacent to the north border of the Havard property. The exact boundaries of these parcels are difficult to ascertain since few of the transactions were recorded; instead recitations of the deed history from later deeds must be used to identify the properties. In 1737 Henry John gave his parcel of 100 acres to his brother Griffith “for the consideration of the love and affection with many other good causes moving me hereunto, as my being maintained with meat, drink, washing, lodging, and apparell by my brother Griffith Jones of the same place for this twenty years past.” It seems likely that Henry did very little clearing or farming of his land. Also in 1737 Griffith sold, for a nominal sum of 5 shillings, a greater part or all of his farm near the Baptist church to his eldest son, Samuel Jones. This farm is well known and the farmhouse is still standing. It was the residence of General Howe during the British encampment in Tredyffrin in September 1777. The barn associated with the farm—the Jones barn—has been deconstructed and is in storage. There are potential plans to reconstruct it in Wilson Farm Park. The third transaction of note from 1737 is the purchase of 105 acres in Charlestown by Thomas John of Tredyffrin. By owning 100 acres of land Samuel and Thomas became voters and served the community through township positions, as was expected of those men who owned land. In addition to the position of constable, the township also had a supervisor of roads, and overseers—usually 2 people—of the poor. These posts were held for one year on a rotating basis. The courts approved the persons nominated for these positions. The court records of these approvals are often the earliest documentation of the existence of townships. As well as performing arrests, the constable was expected to ensure that the peace was kept, and was also responsible for generating the tax roll—a job for which he was paid 3 pence per pound of tax collected. [Note 2] Being constable could be a hazardous position as one of the more common crimes at the time was assaulting a constable! The supervisor of roads kept an eye on the state of the highways and organized their repair by the townspeople when necessary. Descriptions of the state of the roads at the time demonstrate that repairs were only undertaken when they became impassable. The overseers of the poor were responsible for raising and distributing local taxes for the upkeep of the poor. They also had to ensure that non-resident poor did not become a burden on the township. Thomas held all 3 positions in 1754—he must have had little time to do anything else! In 1740 Griffith John purchased a parcel of 176 acres from the commissioners of Pennsylvania. This parcel lay between the land previously owned by Henry John and the northern township boundary. At that time this boundary was called the Bilton line as the Manor of Bilton lay to the north. This Manor consisted of the area west of Valley Creek bordering the Schuylkill River and north of the Welsh Tract. It was given to William Penn's sister, Margaret Lowther, and her family in 1681. In 1753 Griffith John died. In his will he split his property between his sons, excluding Samuel who had effectively received his inheritance through his land purchase of 1737. John John received 150 acres and Thomas John received 176 acres. Griffith's son, William, had already died, so the 100 acres originally purchased by Henry John was bequeathed to William's son—also named Griffith John—but was to be held in trust until he reached the age of 21. This last bequest was never executed. Instead, by a deed of assignment, it is stated that in 1752 deacon Griffith signed the back of the original deed of Henry John and thereby transferred the land to Thomas John. Griffith John junior settled in Charlestown, where he ran a sawmill, probably on Pickering Creek. There is no deed showing that Thomas John sold the 105 acres in Charlestown he had purchased in 1737 and he certainly did not own it when he died. The suspicion must be raised that he transferred that property to Griffith John junior in exchange for the property in Tredyffrin.

After his father's death, Thomas owned two parcels of land in Tredyffrin, one of 176 acres and the other of 100 acres. This is supported by his tax assessments. They also show that Thomas was clearing approximately 15 acres of land per year, as can be seen from the following table: [Note 3]

Initially these parcels were free of mortgages, but being short of money Thomas mortgaged both. The larger parcel was mortgaged to a lender from Philadelphia. The other was mortgaged to a group of local residents including the Reverend William Currie.

Surveyor and instruments. After Thomas' death his land was sold to help repay his debts but the land had to be surveyed first. The surveyor's instruments at the time were a theodolite and a chain. Twenty-year-old Anthony Wayne—later General Wayne—was the surveyor. The estate documents show he was paid £1 while Daniel James, the carrier of the surveying chain, was paid 2s 6d. Gunter's chain, invented by an Englishman, Edmund Gunter, around 1600 is 22 yards in length. The chain was made with 100 links, to ease the calculation of areas. Many city blocks are a multiple of a chain and it is also the length of an English cricket pitch. Before this time measures of area had not been consistent. The Domesday book, for example, written around 1100, described the dimensions of estates using the terms “virgates,” enough land for a single person to live on, and “hides,” enough land to support a family on. The perch—also called rod or pole—was originally defined by the amount of land a person could work in a day, which was 4 square perches. An acre was the amount of land a team of oxen could work in a day. Using Gunter's invention there are 10 square chains in an acre and 640 acres in a square mile. A perch was used both as a linear and an area measure. There are 4 linear perches to a chain and therefore 160 square perches to an acre. Thomas had tried to sell his land before he died as can be seen from the following advertisement from The Pennsylvania Gazette: March 8, 1764 TO BE SOLD, A Tract of Land, situated in Tredyffryn Township, Chester County, within 20 Miles of Philadelphia, near Mount Joy Iron works, containing about 276 Acres of Land, with Allowances; 90 Acres cleared, 13 of which is Meadow, and as much more may be made, the rest well timbered and watered; a Lime Stone Quarry, with a Kiln ready made, and Convenience of making several others. There is on said Tract two Dwelling houses, Barns, Stables, Spring- house, and other Out houses; a young bearing Orchard of above 100 Apple Trees, Part grafted Fruit, situated in a very pleasant Part of the County, within two Miles of three Merchant Mills, and a Mile from the River Schuylkill. Any Person or Persons inclining to purchase the same, may apply to Thomas Jones, living on said Premises, and know the Terms. The Title is good. Two limestone quarries can be seen today on the Stirling's Quarters property. Nearby is an earthen ramp that is probably a loading ramp for a kiln although there is no observable trace left of the kiln. After Thomas' death the courts gave the sheriff the responsibility for selling his land. The following are the sheriff's advertisements: March 20, 1766 The Pennsylvania Gazette To be SOLD by public Vendue, on the 1st Day of April next,, A Plantation, situate in the Great Valley, in Tredyffrin Township, Chester County, containing 100 Acres of Limestone Land, with a Stone Dwelling house thereon, with tow Rooms on a Floor, and a Cellar underneath, a young bearing Orchard, and some Meadow made, and more may be made with small Expence, it being Part cleared already, and has a constant Stream of Water running through it, wherewith the whole may be watered. The Vendue will be held on the said Plantation, at 3 o'clock in the Afternoon, where the Conditions of Sale will be made known by ROWLAND RICHARD N.B. The Plantation is convenient to a Forge, several Merchant Mills, and Places of Worship, about 18 Miles from Philadelphia. The stream mentioned in the above advertisement is probably Stirling's Run, which is just west of Stirling's Quarters. March 12, 1767 The Pennsylvania Gazette BY virtue of a writ of levari facias to me directed, on Wednesday, the first day of April next, will be sold by vendue, on the premises, at 10 o'clock in the morning, a certain messuage or tenement, with about 176 acres of mostly woodland thereunto belonging, situate in Tredyfryn, in the said county, bounded by lands of Henry John, the line of the manor of Bilton, and other lands of Thomas John deceased, late the estate of said Thomas John, seized and taken in execution, and to be sold by JOHN MORTON, sheriff

The Reverend William Currie purchased the two parcels of 176 and 100 acres from the Sheriff. Almost immediately he sold a western portion of 200 acres, but records show he was then left with 200 acres! The additional 124 acres seemed to appear from nowhere. There is a reference to a third purchase in the documentation for the sale of the 200 acres, but it does not seem to be recorded. Thomas John was only taxed on 276 acres. The 200 acres that William Currie retained is now known as Stirling's Quarters farm after Lord Stirling, who resided there during the 1777-78 encampment at Valley Forge. Currie lived on the farm for over 35 years. The property now forms the western end of Valley Forge National Historical Park. It was Samuel and David Jones who purchased the 200 acres that Currie sold in 1767. This Samuel Jones was probably the brother of Thomas. It is not clear which of a number of David Jones in the area at the time was the other purchaser. They financed their purchase with a mortgage from William Currie! Surprisingly, Samuel and David Jones did not hold onto the land. Instead, within the year, they sold it a Philadelphia resident, Edmund Physick. They did not pay off the mortgage for another 5 years. It seems that William Currie considered them good credit risks as the loan was no longer backed by any security.

The funeral expenses for Thomas were £13 1s 11d including £2 10s for the coffin and 5s for digging the grave. Presumably he was buried at the Great Valley Baptist Church. Although there are graves for some of the other members of his family, his grave is not identifiable.

In 18th century English law all property in a marriage was the responsibility of the husband, but he had an obligation to support his wife. The right of widow's dower was developed in English common law, which extended this obligation after the husband's death. The colonies adopted this right of dower. This gave the widow right to one third of the husband's property in her lifetime. This right took precedence over the rights of creditors. If a husband was in debt when he died, the option of taking the dower, rather than her inheritance, could be advantageous to a widow. Unfortunately for Hannah the right of dower was restricted in Pennsylvania. One of the ways it was reduced was that the real estate was used to pay off creditors before the dower was taken, unlike English common law where the dower was protected from creditors. So Hannah received nothing from her husband's estate and had to purchase part of the family personal property in the auction as shown in the following table:

Gum tree boxes. Photographed at the Mercer Museum, Doylestown, by the author, July 2005. Gum trees, or gum tree boxes, were cylindrical wooden containers used around the home and farm as all-purpose bins. They were made from the trunks of black-gum trees, which almost always become hollow with age. The trunk was cut into sections, the remaining dead wood was removed from the inside, and boards were pegged to the bottom of each section. The resulting sturdy containers were used for all kinds of liquid or dry storage in the stable, farm, or home. The fact that Hannah purchased an English, rather than a Welsh, bible suggests she was not of Welsh extraction. The list of property that Hannah purchased suggests that she planned to farm. It is not clear where Hannah planned to live and farm. Perhaps she rented the Edmund Physick property.

Thomas' property was sold at a vendue on the 20th of November 1766. The list of the property, the buyers, and the prices they paid, is given in the Thomas Jones estate documents. In listing the items sold at the vendue, the original spellings have been used. The costs of the sale were:

The following are the animals sold at the vendue:

Tax records of the period show that these numbers of animals are typical for local farms. A shoat is a young pig just after weaning. There are no records that show that chickens were kept on the farm. From the sale you can also see what crops Thomas produced on the farm:

Left: Sled. Photographed at the Mercer Museum, Doylestown by the author, July 2005.

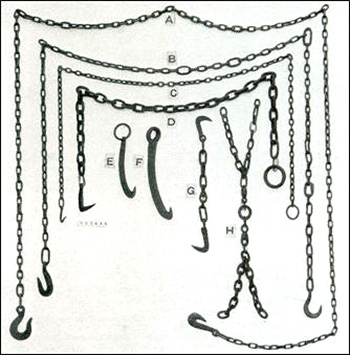

Left: Timber chains. From Ancient Carpenters' Tools: Illustrated and Explained... by Henry C. Mercer. 5th ed. Horizon Press, 1975; reprint, Dover Publications, 2000. All the tools that Thomas owned would probably have been made in England. There was very little steel manufactured in the colonies at the time; the making of steel had been outlawed by the British Parliament. The making of high quality crucible steel was invented by Benjamin Huntsman in Doncaster and Sheffield in England around 1740. This technology was not transferred to the United States until much later. One factor that probably delayed the transfer was the special type of clay needed to make the crucibles. Thomas Jones' steel tools, such as saws, probably would have been imported from England. In order to undertake carpentry Thomas would have had to first cut down trees and transport them to his working area. In the winter he would have used a sled to move the wood and timber chains to tie the wood to the sled:

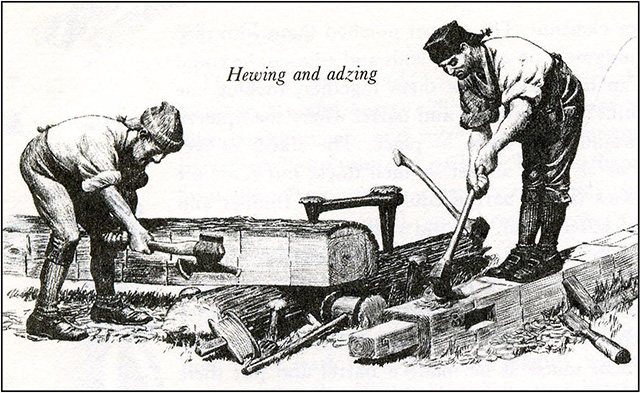

Then he would have had to shape the timbers using a broad ax and adz:

Above: Shaping timber using an adz and broad ax. From Colonial Craftsmen and the Beginnings of American Industry by Edwin Tunis. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

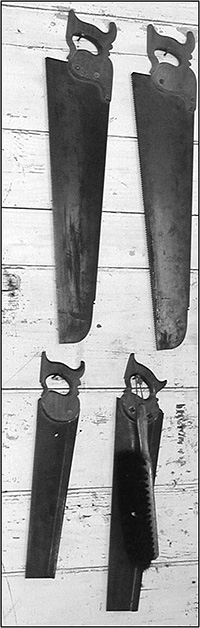

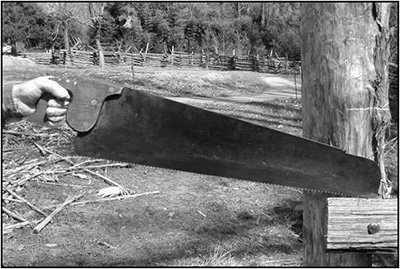

Above: Crosscut saw. Right: Tenant saws. Both photographed at Colonial Williamsburg by the author, March 2005. The cutting of boards required a pit saw but Thomas did not seem to own one. Further cutting used crosscut and tenant saws, and drawing knives for shaping.

Other tools that Thomas owned for shaping included planes, chisels, augers, and gouges. It is not clear what is meant by a lather. It could be leather or it could be a lathe, for turning wood. Given the price obtained it is more likely to have been a leather hide.

Above: Lathe. Photographed at Colonial Williamsburg by the author, March 2005.

Thomas also must have made barrels since he had a full set of cooper's tools:

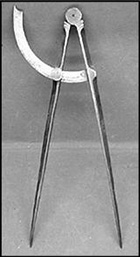

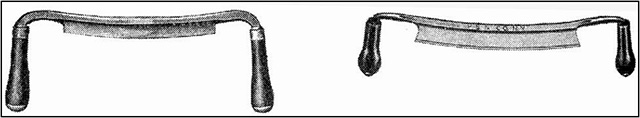

Above: Coopers tools. Top: left to right: adze, compass, howels (4). Bottom: drawing knives. All from the Encyclopedia of Antique Tools & Machinery by C. H. Wendel. Krause Publications, 2001.

Above: Cooper's horse. Below: Tresshoops.

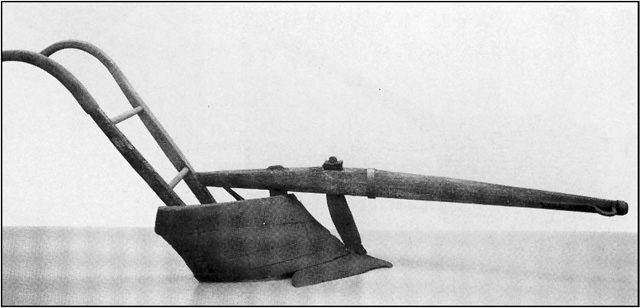

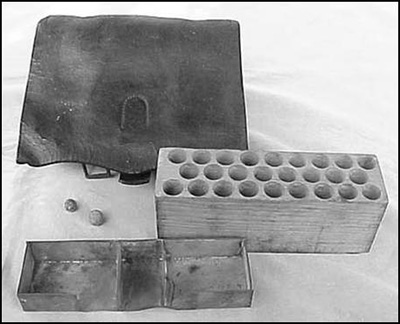

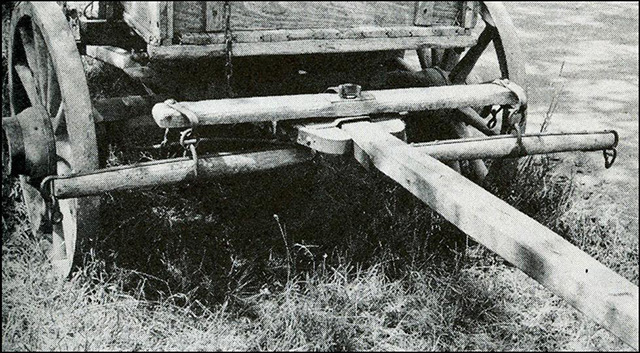

Thomas did not have a complete set of flax tools, just a break which sold for 1s 6d. A snead is the curved handle of a scythe. A whiffletree is the crossbar that is attached to the traces of a draft horse and to the vehicle or implement that the horse was pulling. A cartouch box held charges of powder and bullets.

Above: Early plow. From Pictorial Guide to Early American Tools and Implements by Robert W. Miller. Wallace-Homestead Book Co., 1980.

Whiffletrees. From Encyclopedia of Antique Tools & Machinery by C. H. Wendel. Krause Publications, 2001.

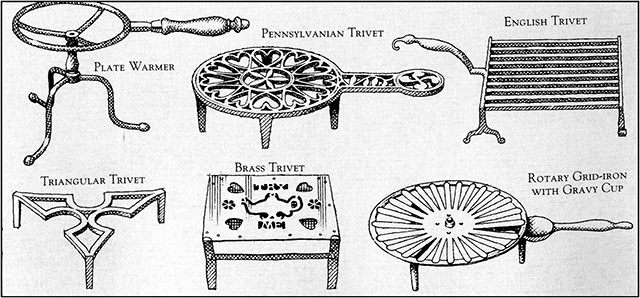

Above: Trivets. From The Forgotten Arts and Crafts by John Seymour. Dorling Kindersley, 2001.

Above: Kitchen items. Photographed at the Mercer Museum, Doylestown by the author, July 2005.

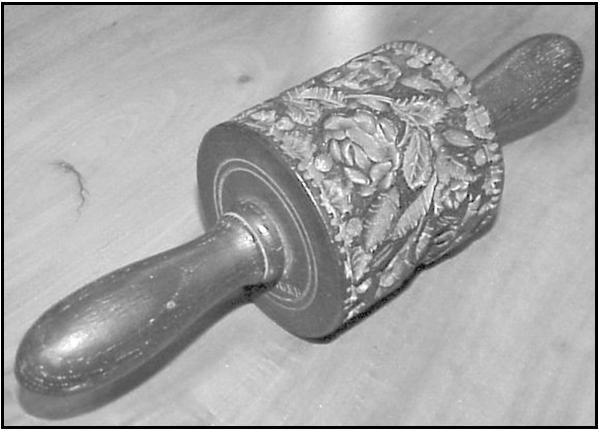

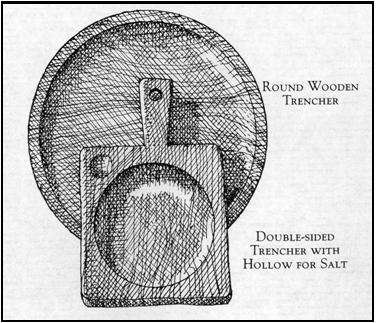

Clockwise from top left: Two butter prints; Cheese fat, a container for shaping cheese. (All photographed at the Mercer Museum, Doylestown by the author, July 2005); Trencher. Originally a slice of stale bread used as a plate. Later it became a wooden plate. From The Forgotten Arts and Crafts by John Seymour. Dorling Kindersley, 2001.

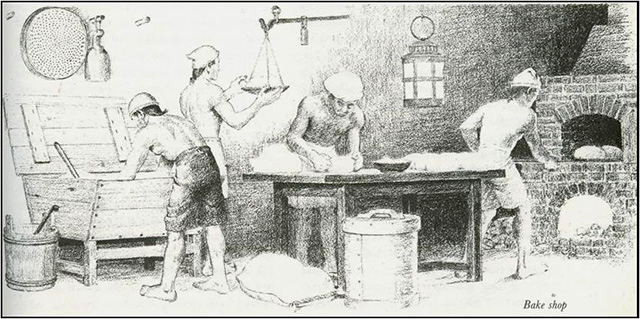

Above: Dough trough. From Colonial Craftsmen and the Beginnings of American Industry by Edwin Tunis. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

The family owned only a small amount of furniture for their house of 4 rooms:

The big wheel could have been either a spinning wheel or the drive wheel for a lathe.

The estate of Thomas John gives a flavor of the life of a local mid-18th century farmer and carpenter in the Great Valley through his property. There are many unanswered questions, such where were the exact property boundaries, and what caused Thomas to get so in debt, which should be the subject of future research.

Thanks go to staff at Colonial Williamsburg and the Mercer Museum, Doylestown for answering my many questions. Mike Bertram is a frequent contributor to this publication and is particularly interested in pre-19th century local history. This article was catalyzed by the discovery of Thomas John's estate documents while researching the life of the Reverend William Currie. Mike's house is located on part of the land previously owned by Thomas John and William Currie. This was a presentation at the January 15, 2006 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||